The relationship between the Edinburgh-born former diplomat and the 13-year-old Puyi began in 1919, with Johnston not only tutoring the boy, but trying to convey to him the world beyond the limited confines of the Forbidden City.

He taught him to ride a bicycle, to use a telephone, and procured him a much-needed pair of spectacles.

For all this, Johnston earned the deep enmity of the corrupt and venal eunuchs who surrounded Puyi, who stole so much of the imperial treasure, and sought to frustrate the close relationship between tutor and pupil.

If you have seen The Last Emperor, or read Johnston’s memoirs, you could be forgiven for thinking that he was the only foreigner to live within the inner sanctum of the Forbidden City. But he was not.

Behind the scenes of classic 1987 movie The Last Emperor in photos

Behind the scenes of classic 1987 movie The Last Emperor in photos

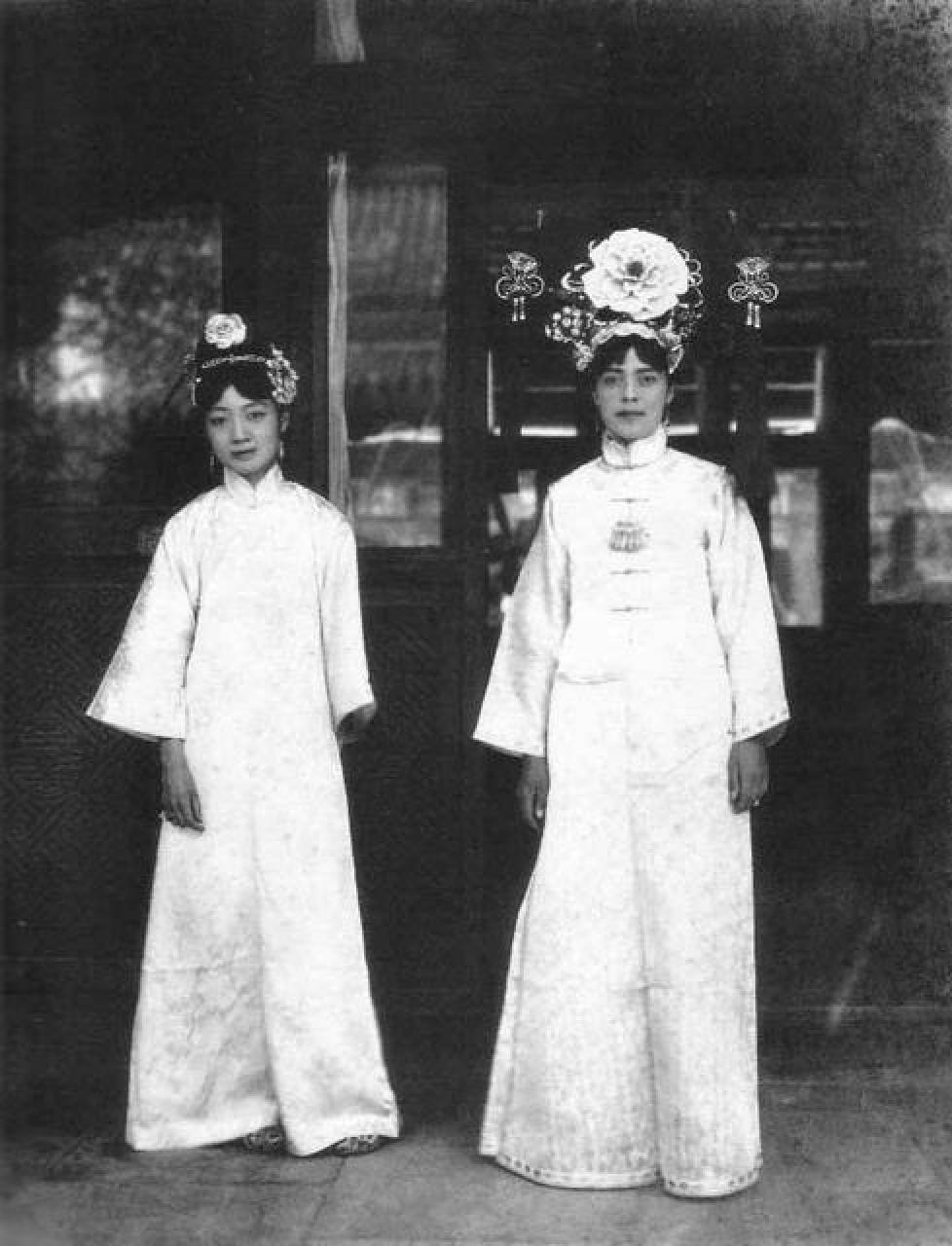

Wanrong (played by Joan Chen in the Bertolucci film) was about the same age as Puyi, and from a noted Manchu Bannerman family. But she was not popular among the staunchly conservative high consorts and former ladies-in-waiting to the late Dowager Empress Cixi.

They still lingered as éminences grises, with their own favourites for the role, notably Wenxiu.

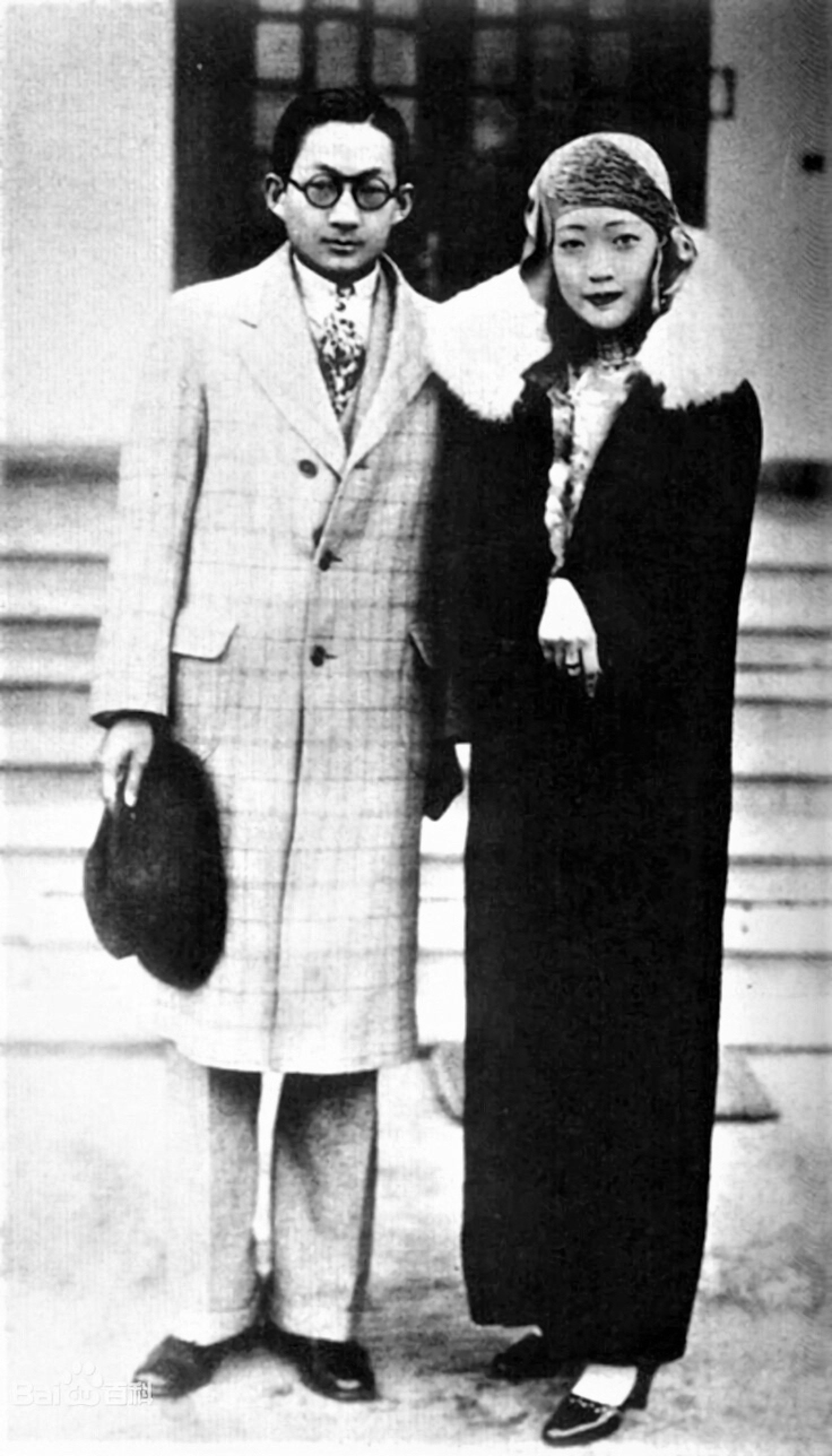

Having grown up in the Westernised atmosphere of Tianjin’s French Concession, Wanrong was considered a rather independent, spirited girl, perhaps a little too fond of foreign ideas and manners.

Her younger brother, Runqi, later wrote, “They taught her [Wanrong] how to bow and behave with the emperor. But she constantly rebelled. She was fed up with the lessons and unhappy about marrying someone she had never met before.” The couple were both barely 16.

Wanrong would occasionally dress in Western clothes, even contemporary flapper fashions, as well as play jazz gramophone records. Those among the conservative elements of the imperial court who had opposed her elevation were appalled. They were about to be even more shocked.

Wanrong had conceded to the match, but her one condition was that she also have a tutor, just as her husband-to-be had Johnston. She wanted to learn English and, despite objections, Puyi authorised her wish and the search for a tutor began.

At first Miriam, the oldest daughter, was selected. After only a few weeks, however, Miriam got engaged and announced that she was returning to the United States to get married and settle in Pennsylvania.

From the outset, the connection between Ingram and Wanrong was different from that between Johnston and Puyi. Johnston, for all his reforming zeal when it came to the emperor’s education, was a rather stiff ex-diplomat approaching 50.

Having just turned 20, Ingram was just a few years older than Wanrong.

Johnston was from Edinburgh and arrived in China by way of Oxford University, to join the Colonial Service. Ingram was born in Beijing in 1902, a “Mishkid” who went on to study at Wellesley College, in Massachusetts, in the US, and then returned to China to consider her future.

Ingram quickly became more akin to a friend to Wanrong than an instructress.

Inevitably, Ingram also found herself up against the intransigence of the palace eunuchs and the numerous interfering high consorts and ladies-in-waiting, who were opposed to any modernisation within the Forbidden City.

The royal wedding was held on a Sunday in late 1922. It was to be the last imperial-style wedding Beijing would see, and the court, although rendered politically powerless, mustered all its impressive pomp and circumstance.

According to the American travel writer Richard Halliburton, who happened to be in Beijing at the time, “At four in the morning the gorgeous spectacle moved through the moonlit streets of Peking […] The entire city was awake and the people thronged the line of wedding procession.”

The main thoroughfares were festooned with brocades, gold dragons and lines of deposed noblemen in full Manchu costume having a last hurrah as the Qing dynasty and the imperial family receded into China’s past. Everyone knew they would not see the like of it again.

Halliburton followed the procession right to the Meridian Gate, the southern entrance to the Forbidden City, which swung wide open to admit the new Empress Consort into the so-called Great Within.

Halliburton, along with the thousands of Beijingers silently watching, could go no further. As the 38-metre-high (125-feet-high) gates swung shut they could only contemplate what Wanrong’s life would now be like.

Inside, Puyi, surrounded by the court, sat upon his Dragon Throne awaiting his bride. Only two foreigners were present at the ceremony – Reginald Johnston and Isabel Ingram.

Richard Halliburton had graduated from Princeton University and decided to journey around the world. Reaching China he had taken a train to Beijing, buying a third-class ticket yet riding first class, dodging the conductors.

In his 1925 memoir, Royal Road to Romance, he admitted to being intrigued by Wanrong and absorbed in the gossip and speculation about her life in the Forbidden City.

“I halfway fell in love with her,” he confessed, fretting over what he saw as her “imprisonment, her isolation” after the Meridian Gate clanged shut behind her.

He determined that, although it was, of course, impossible to meet the enigmatic Xuantong Empress, he could perhaps meet her “tutoress, who was teaching her the speech, modes and manners of the West”.

Halliburton also heard tell that Wanrong wanted herself and Ingram to look as alike as possible, reflecting their close friendship.

It was gossiped about in the old hutongs and in the modern hotel lobbies that Wanrong envied Ingram her pink, glossy nail polish and insisted her friend give her manicures.

Halliburton did call on Ingram, they set up a date and he met her as she slipped out of the Gate of Divine Might, at the rear of the fortress and used by the Forbidden City’s staff. The two spent a moonlit Christmas Eve walking along the Tartar Wall that enclosed the Imperial City and the Legation Quarter (essentially Beijing’s Second Ring Road today).

Halliburton found Ingram to be “petite and quite attractive” and was relieved when she reassured him that Wanrong was well cared for inside the vast and secretive citadel.

As a child in Tianjin, Wanrong had studied the piano, and in the Forbidden City Ingram discovered an organ – ignored, dust-covered, unused – and so encouraged the empress to begin to play again.

It was also alleged in some newspapers that it had been Ingram who suggested the empress adopt the English name Elizabeth. It’s not clear that this was the case.

Officially, Wanrong chose the name after reading of the exploits and reign of Elizabeth I of England, although some suggested that she also recognised a kinship with the so-called Virgin Queen, given the rumoured lack of consummation of the royal marriage (and indeed the couple never did have children).

The first portrait of China’s feared empress dowager was by … an American?

The first portrait of China’s feared empress dowager was by … an American?

Puyi chose the name Henry for himself and even issued an imperial edict informing the public of these new names.

Just how rigorous the educational syllabus was is questionable. Before their wedding, the young people studied for several hours a day. But afterwards, once Wanrong had moved into the Forbidden City, it was more often only an hour a day.

Lessons would invariably be accompanied by tea or lemonade and cakes (often brought from a foreign bakery in Tientsin that Wanrong had known as a child), small bowls of peanuts and even chocolate liqueurs.

Ingram procured foreign newspapers for Wanrong to read aloud to improve both her English and her knowledge of the outside world. She would practise her English writing using a gold fountain pen and a silver ink well.

When English grammar proved a little dull, they swapped to reading Aesop’s Fables aloud.

One of the reasons Isabel Ingram is so little known compared with Reginald Johnston is that she published no memoir of her time with Wanrong. She did, however, keep diaries and notebooks, which have survived and are kept by her descendants.

Each day, Ingram would be escorted in a rickshaw to the Forbidden City by a palace eunuch. From the gates to the Palace of Gathered Elegance she would be carried in a sedan chair by six bearers, and she would sometimes bring in suitcases of her own Western-style dresses for the empress to try on.

She notes in her diaries that sometimes lessons would be suddenly cancelled with the excuse that the empress was “busy”. This, Ingram later found out, was often code for some activity such as flying kites with the emperor, or watching his small pony trot around the lanes of the Forbidden City.

When lessons did take place, “The boy Emperor rarely, if ever, interrupted our study hour.” Sometimes, however, Puyi would join them to talk and share which books he was reading.

“We spoke about England and America. He wanted to know if I went to school at Oxford,” wrote Ingram. Later, as they all came to know each other better, Puyi would conduct impromptu tours through the Forbidden City pointing out its treasures – massive Buddhist artworks here, exquisite jade figurines there.

For Ingram, as she notes in her diaries, the emperor’s arrival caused etiquette nightmares.

Early on during her tenure she had been riding through the Forbidden City in a sedan chair. Her bearers suddenly placed the chair on the ground and knelt, telling her to stand.

Ingram did not understand them, stayed sitting, and then watched as the emperor’s imperial yellow sedan chair passed, Puyi distractedly looking the other way.

Mortified that she may have offended court protocol she explained the mistake to Wanrong. “Oh don’t worry, the emperor is good.” But, the empress also added, “Now you know the protocol make sure you stand next time!”

Life inside the Forbidden City: how women were selected for service

Life inside the Forbidden City: how women were selected for service

Exquisite as the surroundings of the Forbidden City may have appeared, they were bitterly cold in winter. The women practised cross stitching to keep their fingers warm.

In the summer, excuses to miss lessons came more frequently. Wanrong would summon Ingram for an early breakfast, then keep her waiting for hours. Eventual lessons were held outside accompanied by watermelon slices.

The empress was keen to explore the many gardens and rockeries of the Forbidden City, and Ingram recalled wearing a loose summer dress and a large grey sun hat while the empress wore a more constricting and traditional purple gown – but not so constricting that she could not climb across the rocks of the Yuhua Yuan (Imperial Palace Garden).

Wanrong had received a camera as a wedding gift and loved to use it. She took pictures of Ingram, the gardens, her dogs, her brother Runqi, favoured ladies-in-waiting, the emperor and Reginald Johnston.

Although Ingram would repeatedly ask the empress if she could see the photographs once they were developed, she never saw more than a handful – Wanrong was too shy to show her work.

There were sports, too. Puyi had ordered a tennis court built and the couple loved to play. Johnston cited age to avoid playing mixed doubles, but Ingram and Runqi would be roped in, enjoying the game despite the brutal July heat.

This seemingly idyllic world was, of course, not to last. Despite the calm and centuries of tradition inside the Great Within, outside warlord chaos raged across northern China.

Puyi moved from riding his bicycle and giving Wanrong cycling lessons to roaring around on a newly acquired motorcycle. Wanrong had swings installed in the Imperial Garden and Ingram would bemoan having to push her ever higher for hours at a time.

Despite becoming friends and regularly dining together, Johnston notes Ingram only once in his 500-page memoir, and incidentally at that.

During their employment, Johnston was given a residence in the Forbidden City – a two-storey pavilion next to the Yuhua Yuan – and was awarded the Order of the Ruby Hat Button. Ingram lived with her parents.

After her time with Wanrong, Ingram travelled to Mongolia, then scaled Mount Wutai, in Shanxi province, and spent time at a Buddhist monastery. She also contributed several academic papers to The Pennsylvania Museum Bulletin describing items she had seen in the emperor’s private collection in the Forbidden City.

In 1930, she met and married William Mayer, a military man and an attaché at the US Legation in Beijing. After the war, the Mayers settled in Connecticut, restoring a 200-year-old house.

Wanrong followed her husband into exile, began to smoke opium and developed an addiction, and stayed with Puyi as he became the puppet emperor of Japanese-controlled Manchuria.

During the Chinese civil war she was imprisoned in Jilin province without medical attention, still in the grip of her opium addiction. She died in June 1946 of malnutrition and opium withdrawal. She was 39. Her place of burial is unknown.

Isabel Ingram died in 1988, aged 86, in Alexandria, Virginia, in the US.