Instead, Chan depicted how the return to China was changing Hong Kong’s culture and identity. He showed this by filming the small daily occurrences he saw around him. “None of it relates to my political stance. I just try to project what is happening every day on to the big screen,” he told the Post in 1999.

Having spent most of their adult lives working for the colonial government, they have difficulty fitting back into a society undergoing a massive transformation. Do they identify as Chinese or Hong Kong Chinese? How do they resolve their mixed feelings towards the British?

“If you take a step back and look at the whole picture, The Longest Summer is really about the way our society has been changing as a result of the handover,” Chan told the Post.

The film uses plentiful real-life footage shot during the handover, including the fireworks, as well as clips from television news coverage.

When Chan filmed the scenes he was not sure how he would use them, as The Longest Summer was actually made a year later. He simply knew he wanted to preserve images of Hong Kong at the time of the handover on film.

“I don’t know if Hong Kong would value anything on the handover now, but 100 years from now, when people look for a novel or a film to represent that era, I think people will find things like this precious,” he said in 1998.

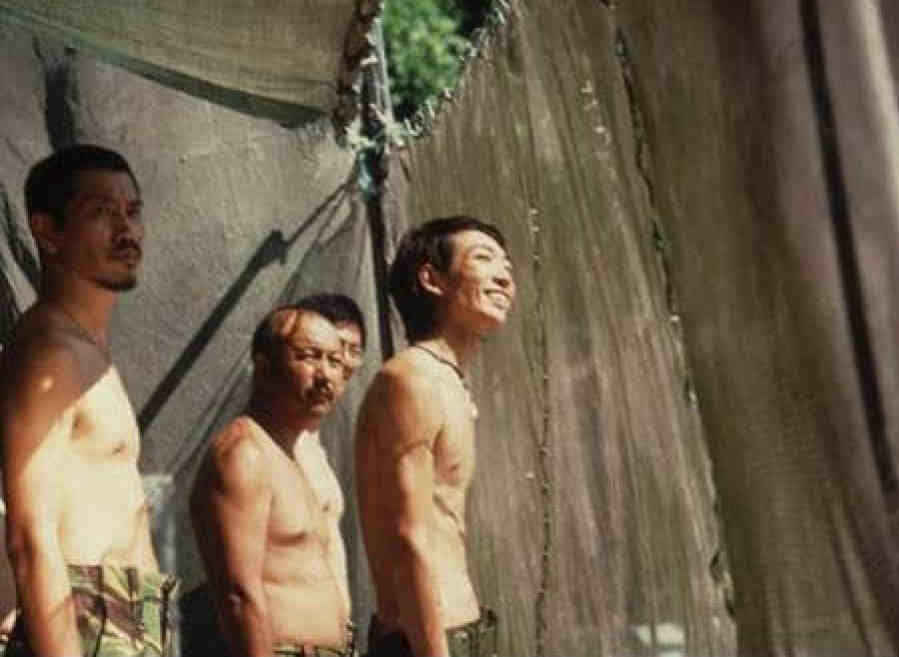

The story sees the unemployed former soldiers turning to crime, following the lead of one of their brothers, played by Sam Lee Chan-sam, the film’s only recognisable actor. Chan has said that the crime scenes were included to please his investors, and he was more interested in showing the incidentals of daily life.

Such concessions to commercial cinema saw the film attacked by some critics, while others found its many scenes of cultural displacement too bleak. Chan re-edited the film after the initial reviews, and claimed he preferred his new cut.

Although Chan’s viewpoint is objective, there is a certain wistfulness for times gone by. “The view of the city lights at dusk, through the plane windows as it takes off from Kai Tak, resonates with a sense of an era long gone,” the Post review said.

Made a year later, Little Cheung is the final part of Chan’s handover trilogy. It is the most neo-realistic of the three films, featuring a slim plot, naturalistic acting and real-life street scenes.

The story focuses on two children – nine-year-old Little Cheung (Yiu Yuet-ming) and his “girlfriend” Wan (Mak Wai-fan) – and Little Cheung’s elderly grandmother.

Chan also wanted to end the trilogy on a quieter note, after the high drama of the previous films. “It’s intended to offer a tranquil and calm narrative,” he told the Post’s Clarence Tsui in 1999.

Little Cheung is the most sophisticated of the three films, and Chan weaves his observations on Hong Kong life into an almost invisible plot about two children with ease.

The film may be about children, but it is never cute – it is touching, pertinent, and even politically provocative.

“The third and arguably the best of director and writer Fruit Chan’s ‘1997 trilogy’, it is more of a piece than the ambitious but flawed The Longest Summer and more fully developed than his critically acclaimed Made in Hong Kong,” wrote Post critic Paul Fonoroff.

Chan told the Post that the story was constructed from newspaper reports of small events that happened in Hong Kong, such as a young boy being made to stand in the street with his trousers down as a punishment.

The story has charm, but there is a sense of physical danger throughout.

Little Cheung works for his father’s restaurant, delivering food. A bright spark, he hires an illegal mainland immigrant, Ah Fan, to help him, paying her an uneven cut of his tips. The two form a bond, but a vicious police crackdown on illegal immigrants sees them parted.

Along the way, Chan takes his time depicting daily life in the working-class district of Kowloon.

Local news – both political, in terms of the impending handover, and cultural – is heavily referenced. The drama of another, famous Cheung plays out on television as Little Cheung goes about his business.

“Chan finds in Tang a potent symbol of certain aspects of Hong Kong on the eve of the handover, such as the old giving way to the new, the place of popular culture in Hong Kong life and even the political consciousness of the inhabitants of the then British colony,” Fonoroff wrote.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.