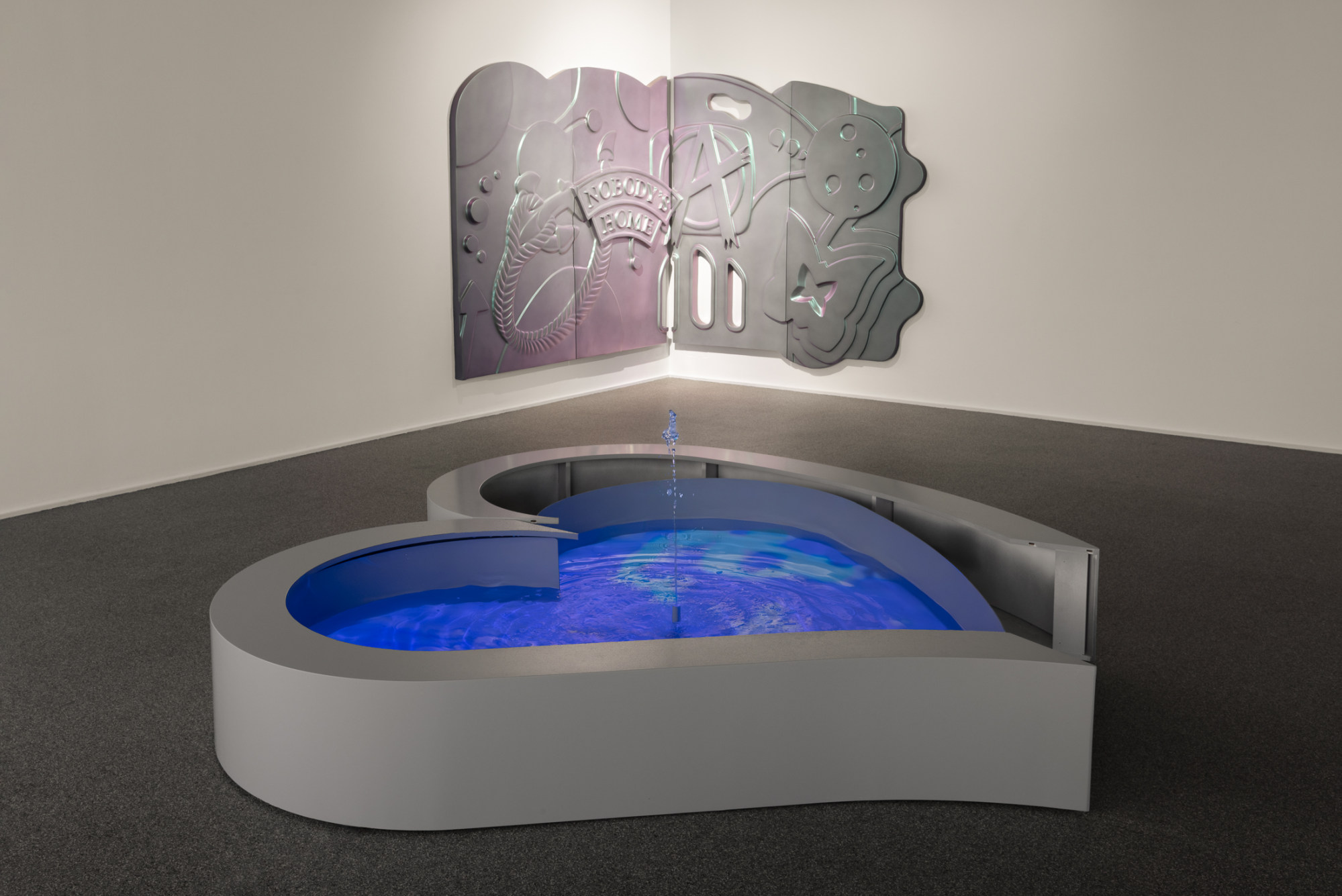

The centrepiece of the major exhibition is an installation called Heart Is A Broken Record. It features a heart-shaped working fountain with images of screaming fans at MCR concerts projected from above.

An audio recording of an excited audience at the start of an MCR concert plays on a loop, stopping abruptly at the point when the band appear on stage, and starting again after a pause.

It is a symbol of fans’ longing for unobtainable objects of desire, Li says. The silence that follows the appearance of the performers in the projection splits the world of the screaming and cheering fans from that of the band.

The work is a celebration of the world that fans create for themselves in the absence of their idols.

“There wasn’t even a shopping mall to hang out in. So I would spend a lot of time online, just reading, as a teenager,” she says on the rooftop of the Swiss Institute, a non-profit contemporary art venue in Lower Manhattan.

“I felt I was more alive when I was online playing video games and reading. All these different media were making me feel much more alive than living physically.”

“Going online began as a way to escape my surroundings, but then I started to use online media as a way to express myself.”

Li was further removed from MCR than their fans in the West because of geography and China’s economic status at the time.

It’s beautiful to be a fan, and that is the identity I am most comfortable with. I am actually a crazy fan

Their edges were deliberately clipped to make sure they could not be resold as new, but it was discovered that some tracks could still be played, and a black market arose.

For Li, the band’s impact was not diminished by the flawed CDs she could get her hands on. After she taught herself English by listening to more MCR albums, she began to identify with their unique brand of emo goth music.

They sang about death and depression but, instead of wallowing in sadness like many emo groups, their lyrics offered positivity and hope, she says.

Her life has been shaped by being an MCR fan. “I was really impressed by what these five guys from New Jersey had done with their lives. They made me think I could do more,” she says.

Her long-distance, indirect relationship with the band is also at the heart of her art. Until 2022, when she finally got to see them play live, her only exposure to MCR concerts had been through watching them online, which led her to investigate the dislocated way that her generation was living their lives.

That became the subject of her research at New York University, where she graduated in 2014 with a master’s degree in media studies.

She has been living in Berlin and in Geneva, in Switzerland, since the Covid-19 pandemic, when the absence of bodily contact became a global experience.

For a 2022 group show called “Where Jellyfish Come From” at Antenna Space gallery in Shanghai, Li created a performance piece called Lord of the Flies.

At the time, she could not get home to China because of travel restrictions, and so she chose 20 people in Shanghai to be her avatars, asking them to dress in her favourite MCR T-shirt.

“I watched it from afar. It really invoked an image of freedom for me. It was a kind of virtual self – it was like having 20 virtual bodies,” she says.

On the ground floor of Li’s New York exhibition, which has a theme of absences and unfixed identity, there is a large installation resembling a half-finished construction project.

It contains shoes that were worn by the Shanghai performers during Lord of the Flies, and there is an embedded screen showing a video of people in army uniforms singing an a cappella version of MCR’s song “I’m Not Okay (I Promise)”.

They are singing in Mandarin, the lyrics Li’s translation of the original ones. The work, called simply I’m Not, is also the name of the exhibition, and it emphasises the cultural dislocation and room for creative interpretation you have when listening to music in a language you do not understand.

While fandom, like Li’s art, thrives on a sense of absence, the thrill of having an in-real-life encounter with one’s idols is still hard to beat.

Recently, Li met the band’s rhythm guitar player, Frank Iero, at a signing in New Jersey on her way to New York to prepare for the Swiss Institute show.

“I had a copy of Flash Art International magazine, and the issue had a picture of the Lord of the Flies performance on the cover. So I showed it to him. It was an amazing experience, as he was genuinely impressed. He told me it was great and asked me for my autograph. I got his and he got mine!

“I came back here to the Swiss Institute and cried. It was so crazy!”

So she is still a fan, then? “Yes, I am a fan,” Li answers emphatically. “It’s beautiful to be a fan, and that is the identity I am most comfortable with. I am actually a crazy fan.”

“Shuang Li: I’m Not” is co-organised by the Swiss Institute and the Aspen Art Museum. It is on view at the Swiss Institute until August 25.