The story of a dog who builds and befriends a robot, adapted from a hit 2007 graphic novel by Sara Varon, is Berger’s first animated film, and follows three live-action films he has directed. The book first caught his eye in 2010.

“I collect ‘no words’ books […] children’s books that have no words,” he says. “After 20 pages […] I realised this was an adult graphic novel.”

Certainly, Varon’s work feels in step with the current movement in cinema; at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival, the feline-driven Flow and the Auschwitz story The Most Precious of Cargoes showed that adult animations are in vogue again.

It wasn’t until 2018, as Berger was considering his next project, that he read Varon’s book again. “This time, when I get to the end, I have tears in my eyes,” he says.

The way he describes it, Berger was already visualising the film as he was reading it. “In a way, I was making the film as I was reading this book.”

With no dialogue, Berger set out to craft a pure silent movie. “I really love this sort of storytelling,” he says. “And my favourite period of cinema is the [19]20s. That for me is the golden era of cinema when silent movies really got complex. I feel very comfortable telling stories visually.”

His live-action films have always been inspired by this pioneering era of filmmaking. Both his 2003 debut Torremolinos 73 and his third film, the 2017 comedy-fantasy Abracadabra, contain little dialogue. “There could be scenes five to 10 minutes long [with] not even one word [spoken],” he says.

His second movie, Blancanieves (2012) – a black-and-white film that borrows from the Snow White fairy tale – was created entirely in images, with just a few intertitles.

For Robot Dreams, created via two “pop-up” studios in Spain and using around 130 animators, Berger borrowed from the masters: Buster Keaton, Jacques Tati and, most of all, Charlie Chaplin – in particular his masterly work City Lights.

I think it’s not like a children’s book, where everybody’s happy and everybody’s good. It’s closer to real life

“What he did with City Lights […] it was already 1931, the sound era had started. But he wanted to tell a complex story only using visual storytelling. So in that sense, we were always watching his film while we were preparing this film.”

After gaining the rights from Varon in 2018, Berger was given “carte blanche” to do as he wished with the adaptation. “When I met with her […] I said, ‘I’m going to keep the soul and the spirit of your book because that’s the reason I’m going to make this film.’

“I never planned to make an animation film in my life. It never was in my strategy […] for me, it was very important. [I said:] ‘Don’t worry, I’ll take care of it.’ Because it’s going to be in the same spirit as your book.”

As much as he wanted to keep that spirit, Berger knew he would need to expand on the author’s slim volume. “If I translated the graphic novel into a film, it would have been probably a 30-minute film. So I had to expand the story and the characters.

“Also, in a comic book it’s just one artist working alone. And in a film like Robot Dreams, there are more than a hundred artists working, so the complexity and the detail is more epic.”

One of the major changes was to clarify the setting – in Varon’s work, it was just an anonymous urban area occupied by animals acting as if they were humans.

“In the book, the protagonists were robot and dog,” he says. “And in the film, the protagonists are Robot, Dog and New York. This is something that I brought to the adaptation – New York will be a third protagonist.”

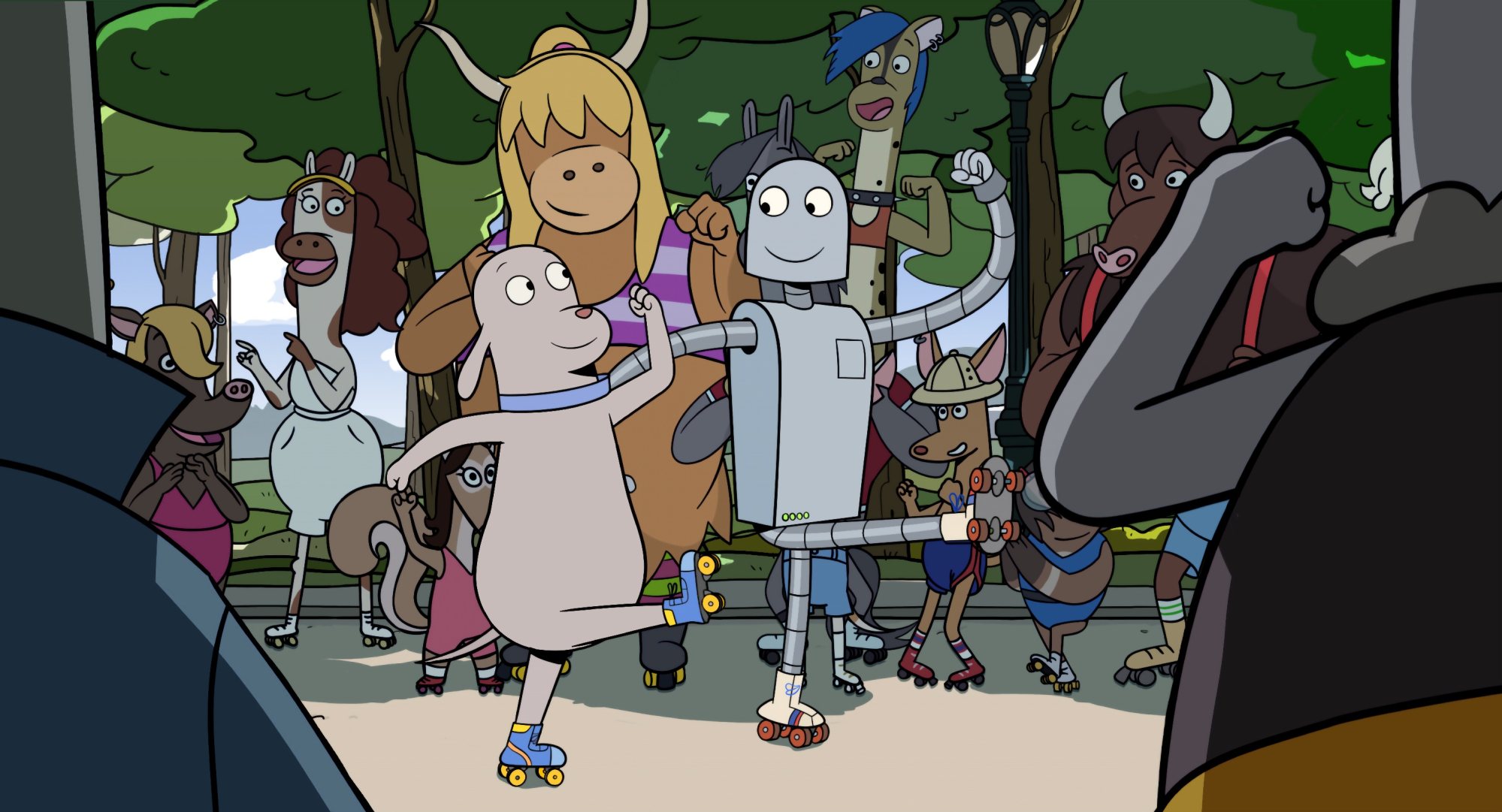

The detail of city life in the Big Apple in Robot Dreams is exquisite, from trips on the subway to shots of the Queensboro Bridge famed for its appearance in Woody Allen’s Manhattan.

You could also look at Steven Spielberg’s E.T. The Extra Terrestrial, with the boy Elliott’s friendship with the alien being akin to Robot Dreams’ relationship between the dog and his robot.

“What people remember from E.T. is the emotional part, and that they had a roller-coaster ride. And I would like to think that there are elements [like that in Robot Dreams]. Of course, Steven Spielberg is the master. I’m just an apprentice. But I really think that there are connections with that film.”

Indeed, when the story’s canine protagonist gets agonisingly separated from his new robot chum, you could read it as a nod to the moment Elliott and E.T. are torn apart.

“I think it’s not like a children’s book, where everybody’s happy and everybody’s good. It’s closer to real life. If we think about all fairy tales, or even if we think about Disney films […] you think about Bambi. Bambi’s mother died early in the film, you know? And if we think about Grimms’ [fairy] tales, they’re really grim!

“I think that somehow, in the last two decades, especially the last decade, children’s films […] have been too sweet and too far away from real life.”

As Robot Dreams unfolds, Berger layers the narrative with a series of dreams – or even nightmares – as the robot gets trapped at the beach, which is locked up for winter.

“Some of the dreams, you don’t know if it’s a dream. And even if you know that the film is called Robot Dreams, you get so into the story, then suddenly, ‘Wow, it was a dream.’”

In one of the crueller moments, a group of rabbits pull a helpless creature apart. “That appears early in the graphic novel. So I realised, ‘Oh, I thought this was a children’s book. Maybe it’s a children’s book and an adult book as well.’”

Berger’s biggest delight – apart from going to the Oscars – was premiering the film in Toronto, where he finally got to show it to Sara Varon.

“I was sitting next to her, and I was not watching the film, just her face. As the film starts, her face starts smiling and opening. And I could only look at her. And if we wouldn’t have been like that, I would have been very sad and very disappointed because I promised her that I was going to keep the spirit of the film.”

A dream come true, you might say.