“Congress has revived with two yatras [cross-country marches by its leader Rahul Gandhi] and a spirited campaign. It has regained lost ground in northern states such as Haryana and Rajasthan. In direct contrast with the BJP, it has fared much better than in the two previous elections,” said Uday Chandra, assistant professor at Georgetown University.

“The election is a stepping stone to a productive five years ahead,” he added.

Analysts concur that Congress has come a long way since the 52 seats it won in 2019, compared to the BJP’s 303, but they say it still has much to do before it can hope to return to power in the future.

The shaky sentiment within the party was evident during this election when its de facto leader Gandhi switched his constituency from Amethi to Raebareli in Uttar Pradesh in the middle of the seven-phase election, after being defeated by BJP leader Smriti Irani in the last polls.

Instead, party loyalist Kishori Lal Sharma, a relatively obscure figure, was asked to fight Irani from Amethi this time. But the tables later turned after Rahul’s sister, Priyanka Gandhi Vadra, led the campaign to thump the BJP in both constituencies.

Meanwhile, Gandhi won from another constituency as well, Wayanad in the southern Indian state of Kerala, and now has to choose between two constituencies.

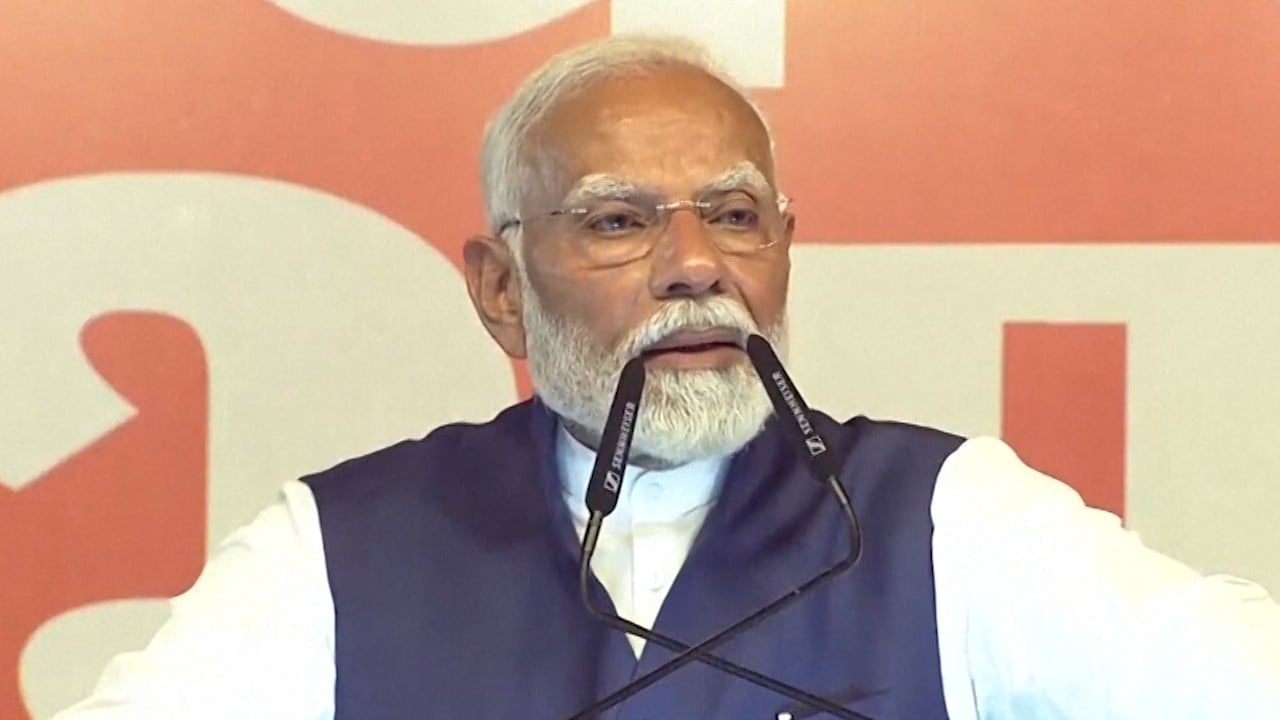

In contrast, the BJP has fared poorly and lost even from Faizabad, home to the celebrated opening of a Ram Temple in January on the site of a demolished mosque. Modi, who was the dominant figure in the BJP’s campaign, only scraped through to a victory in the nearby town of Varanasi with the slimmest of margins.

Gandhi, who was once derided as a pappu or a fool by the BJP, made a stronger connection with voters by focusing on the rising costs of living, unemployment and fanning concerns that the BJP may amend India’s secular constitution.

“The results offer an opportunity to Congress for renewal and growth,” said Pratik Dattani, founder of London-based think tank Bridge India.

“But its vote share across India did not go up substantially, up by only 1.7 per cent. So the party has a long way to go before it.”

According to Dattani, Congress’ party structure has to be more democratic and its leadership has to transition to a younger team that can be groomed for the 2029 election.

Congress contested fewer than 350 seats in the parliament’s 543-seat lower house this election, ceding seats to alliance partners in the INDIA bloc alliance as part of a strategy to field one common candidate against the BJP to avoid undercutting each other.

But analysts say the move also reveals that Congress is far from its heyday in the 1990s when it used to be a dominant force in provinces such as the western state of Maharashtra, which accounts for the second-highest number of parliamentary seats.

What’s next for Congress?

The Gandhi family – which has produced three Indian prime ministers – is likely to remain at the helm of Congress, particularly following the election results, analysts say.

“I expect the Gandhi family to continue to be in charge. Without them, Congress loses its branding,” Chandra said, noting that both Rahul and Priyanka had been pivotal to the party’s campaign success in this election.

Despite this, the party’s chances of becoming a formidable force again under a new generation has suffered, with many promising leaders having left in recent months and key roles gone to favoured stalwarts.

In January, Milind Deora ended his family’s 55-year association with Congress to join a faction of the regional Shiv Sena party. The episode was almost a repeat of Jyotiraditya Scindia, another promising leader, who walked over to the BJP in 2020.

Besides grooming new leaders, the party needed to boost outreach significantly and follow up with attractive programmes for farmers, youth and women, Chandra said.

Analysts say while the opposition INDIA alliance has done well by securing 232 seats this election, Congress should bide its time to woo coalition partners over.

The BJP is dependent on two key coalition partners, Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United) and Chandrababu Naidu’s Telugu Desam, to come back to power for a third term.

Ajay Darshan Behera, an international-studies professor at Jamia Millia Islamia University in Delhi, said the coalition government might not last the full five-year term because of the possibility of personality clashes among the coalition partners.

“That is why the opposition appears to be confident. They believe Modi won’t be able to maintain the government’s stability,” he said.

The weakening of the BJP’s grip over India’s government could provide the space to other political parties, including Congress, who have lagged far behind in accessing financial and organisational support, analysts say.

At the same time, Congress would need to consistently create a counter-narrative to Modi’s mass messaging that has made him one of the world’s most popular leaders in the last decade, Behera said.

“Finally, it has to revive its grass-roots organisational structure and start working among the masses for the next general election,” he said.