From car registration plates to phone numbers, here are five ways Chinese people seek to maximise their good luck through auspicious numbers.

1. Buildings

In Chinese culture, 4 is associated with misfortune because its pronunciation in Cantonese and Mandarin is similar to that of the word for death.

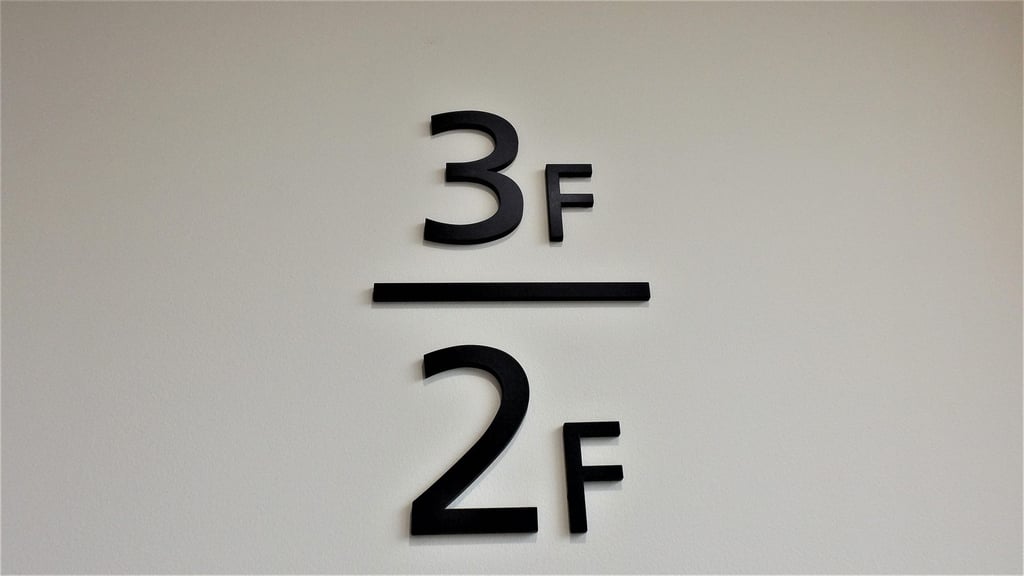

To avoid bad omens, some property developers in mainland China and Hong Kong “omit” the fourth floor and higher floors containing a 4 (such as the 14th and 24th floors) in their buildings.

The lifts in such buildings display the third floor as normal, but label the actual fourth floor as the fifth.

In addition to skipping the fourth floor, some traditionalists will choose to forgo the 13th floor because 1 plus 3 equals 4, and this makes 13 unlucky.

In contrast, flats on building floors containing the number 8 – which is phonetically similar to “fortune” in Cantonese and Mandarin – and 9 – similar to “longevity” – are highly sought after, as they are said to bring good fortune and wealth to whoever lives on them.

2. Car registration plates

The significance of auspicious numbers in Chinese culture extends to car registration plates, for which lucky number combinations are said to bring prosperity and good luck.

For example, 888 – triple fortune – is a coveted combination because it indicates the potential to get rich again and again. Similarly, 999 – triple longevity – reflects the hope for eternal blessings.

In 2016, the number plate “28” was sold at auction for HK$18.1 million, a record high price at the time for a Hong Kong registration plate.

Because 2 sounds like “easy” in Cantonese, when the digits 2 and 8 are said together it sounds like “easy to prosper”.

Before that, the licence plate “18” (“definitely will get rich”) was sold at auction for HK$16.5 million in 2008, and the plate “9” (simply “longevity”) was auctioned for HK$13 million in 1994.

3. Phone numbers

Phone numbers represent another way to inject some good fortune in your life, and people look for numerical combinations that reflect certain auspicious phrases.

For instance, the combination 118 is considered propitious. This is because 1 sounds similar to the word for “day” in Cantonese, and so 118 indicates that the owner of the number will gain fortune every day.

A combination like 168 in a phone number is also lucky as 168 indicates “good fortune all the way”. Because 0 sounds similar to “year” in Cantonese, a phone number such as 98016888 can be taken to mean “from the year 1998 onwards, there will be good fortune again and again”.

And while the combination 666 might have evil connotations in the West, it is considered especially lucky in Chinese culture as 6, when repeated, indicates “everything will go smoothly” in Mandarin.

As a result, 666 is viewed as a positive combination in phone numbers.

4. Dining

When it comes to meals, the Chinese tend to avoid serving seven dishes on a table, especially during celebrations, because the number 7 is associated with loss and endings.

Especially in Mandarin, 7 sounds like “to go”, and there is also a ritual of preparing seven courses for a feast during funerals. Mimicking a funeral ritual is said to bring misfortune and portend a future death, so the number 7 is a no-go.

For good luck, one should aim to have an even number of dishes on the table, as there is a general belief in Chinese culture that good things come in pairs.

5. Major events

To maximise their luck, individuals and companies choose auspicious dates for significant events such as weddings and official openings or launches.

For weddings, lucky dates can range widely, as it depends on the couple’s respective birthdays and those of their parents – it is best to consult a feng shui master to determine which wedding dates bring the highest chances of a long, successful marriage.

As for other events, you generally cannot go wrong with dates featuring the number 8. In 2008, the opening ceremony of the Beijing Summer Olympics began at 8pm on August 8 – a time and date specifically chosen for its auspiciousness.

As part of the ceremony, 2,008 drummers played the fou, an ancient Chinese percussion instrument.