“The state government ought to be ashamed of itself,” Shashi Tharoor, a former union minister of state and a current parliamentarian, told reporters on Tuesday. “There is a system and that system has let the women of Kerala down. That system has betrayed the values of the industry that they seem to promote in their art and cinema.”

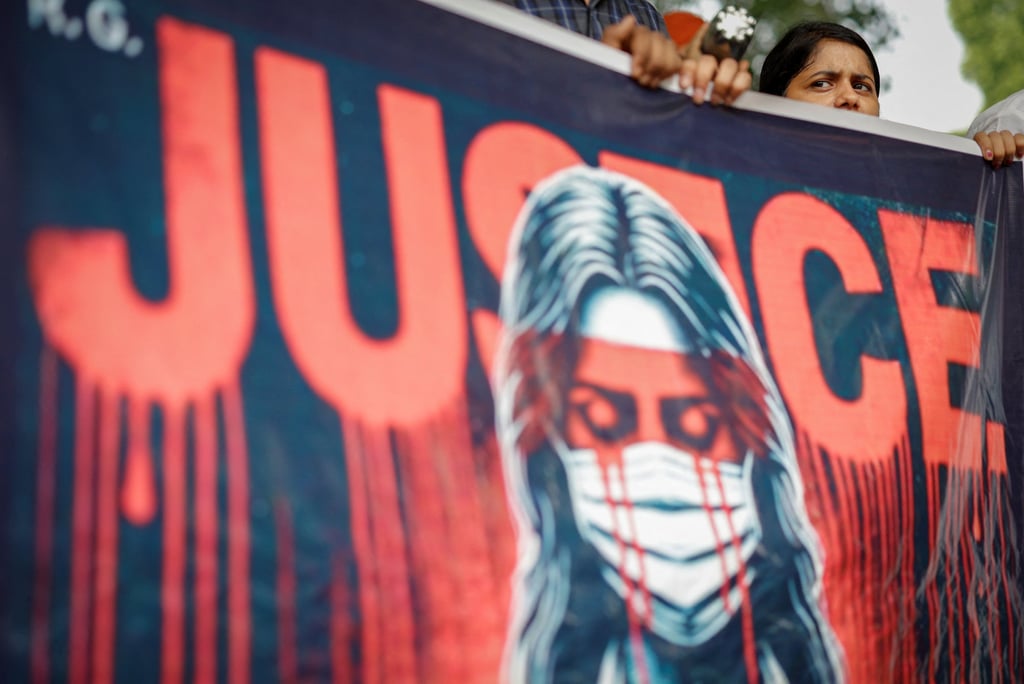

The disclosures come on the heels of the doctor’s case, which has incited national outrage and brought attention to brutal cases of sexual assault in the country. The rape and murder of the 31-year-old doctor at RG Kar hospital in Kolkata on 9 August has sparked protests by doctors and others in cities across India.

The Kerala investigation found that women experienced at least 17 different forms of exploitation, ranging from sexual demands as a condition for entering the film industry to abuse and assault.

“Throughout our study, we found that the Malayalam film industry is controlled by a small group of producers, directors, and actors – all male,” the 235-page report said.

Women who agreed to provide sexual favours were given degrading “code names” by influential men. To protect the victims’ identities, certain portions of the report have been redacted.

The three-member committee, led by former Kerala High Court judge K Hema, completed the controversial report in 2019. However, its release was delayed due to the sensitive nature of its findings.

The Kerala state government was compelled to establish the panel in 2017 after a prominent Malayalam actress was abducted and sexually assaulted by a group of men, leading to the implication of a popular male star.

The incident sparked widespread protests by women’s rights groups, prompting the state government to investigate the pervasive exploitation of women in Kerala’s film industry.

Leading actors and technicians subsequently formed the Women in Cinema Collective (WCC), the first group of its kind in India, to champion women’s rights within the industry.

Government inaction

“If any of those who testified before the Hema Commission come forward with complaints, appropriate action will be taken. No matter how high-ranking, everyone will be held accountable before the law,” Kerala’s Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan told reporters on Tuesday.

However, the state government’s reluctance to press charges and its decision to ask victims to re-register their complaints individually have been met with strong criticism.

“If victims are required to file new complaints, the Hema Commission’s work becomes a futile exercise,” said Jebi Mather, president of the women’s wing of the Congress Party in Kerala and a member of the upper house of India’s federal parliament.

“The government is acting at a snail’s pace. Their plan to organise a conclave is misguided. Conclaves are suited for tourism development or investment drives, not serious issues like sexual harassment. You don’t place criminals and victims in the same room to discuss solutions,” Mather told This Week in Asia.

Bina Paul, one of the pioneering women technicians in Kerala’s film industry, said systemic changes were essential to improving the treatment of women.

“Key changes should include the establishment of proper internal committees on all film sets, with regulations ensuring adequate facilities for women. Grievance redressal mechanisms must be in place. Recruitment and other processes should be transparent and professional,” Paul, a WCC member, told This Week in Asia.

“For well-intentioned men in the industry, they need to stand by their female colleagues and ensure no human rights violations occur in the workplace,” she added.

Prominent filmmaker Jeo Baby, known for his women-centred films, voiced his support for the WCC. “I fully support the WCC, and this is the right time for a major change in the film industry,” he told This Week in Asia.

‘Socially inferior and sexually available’

Kerala’s vibrant film industry is one of many regional film sectors across India, producing some of the country’s most critically acclaimed films.

Compared with other regional industries, Malayalam cinema is often lauded for its progressive storytelling, offering gender-equal roles, age-appropriate characters, space for sexual minorities and embracing literary giants.

Against this backdrop, the revelations of widespread sexual exploitation in Kerala’s film industry are significant. Analysts say such practices are rooted in the industry’s foundations.

“Regional cinema in India has traditionally been funded by feudal interests and usurious capital – often provided by moneylenders or landlords,” said J Devika, a historian at the Centre for Development Studies in Kerala.

“Actors were drawn from communities denigrated in the caste hierarchy. These women were treated as socially inferior and sexually available,” said Devika, a feminist and social critic.

Acting was seen as a marker of social inferiority and sexual availability

“This culture has persisted for a long time and what we are witnessing today is a remnant of it. Women of decent birth were not expected to become film actors. Acting was seen as a marker of social inferiority and sexual availability,” she added.

Devika agreed that the Kerala government was hesitant to act strongly against the perpetrators as it meant taking on influential people in the film industry.

“Actors and films-related associations are extremely powerful … The government doesn’t want to run the risk of acting against them. The so-called mafia which runs the cinema industry … They’re important sources of support for the political parties,” Devika said.