As pioneers at the forefront of immersive storytelling, Animal Repair Shop and its consumer brand Infinite Rabbit Holes are working on next-gen consumer products at the intersection of the physical and virtual world with their upcoming at-home alternate reality board game The Arkham Asylum Files: Panic in Gotham City.

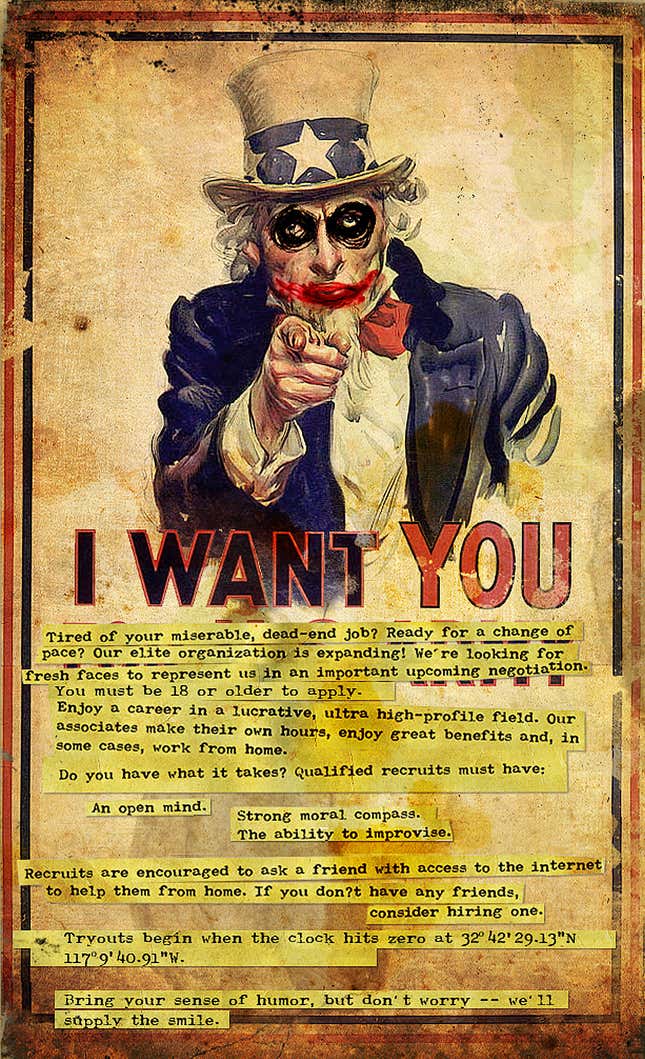

Where you might know them, however, is from the stunts they pulled during Christopher Nolan’s marketing campaign in 2007 for The Dark Knight that would forever change movie studios’ presence at San Diego Comic-Con. The “Why So Serious” initiative was an ARG campaign that swept the globe just as the internet and movie blogs started taking off with the pop culture nerd generation. It involved “11 million participants, 75 countries,” according to Michael Borys, senior VP of interaction design, as he showed io9 the fateful Joker dollar bill when we visited the Animal Repair Shop offices. “It all started from this dollar bill—made 11,000 of them. It was handed out as change for Comic-Con. At the bottom it wouldn’t say one dollar, it would say ‘Why so serious?’” Naturally, curious minds picked up on the mystery created when the phrase was transformed into a URL. “Once there, fans would be asked to join Joker’s army at a certain location during a certain time.”

Alex Lieu, the chief creative officer of Animal Repair Shop and Infinite Rabbit Holes, spearheaded the team including Borys under the banner of 42 Entertainment on the ambitious campaign. “Maybe six weeks before Comic-Con we were meeting with the Nolans and they said, ‘We don’t want to show any footage at Comic-Con of the movie. We don’t want to bring in the actors and have them interviewed or talk about the movie, but we want you guys to make us the most talked-about thing at Comic-Con.’ We’re like, ‘OK.’” He pointed out that this was before Comic-Con was known for doing activations in the Gaslamp District that surrounds the convention center—like promoting The Walking Dead with zombie hordes or offering “tours” of Game of Thrones’ Westeros. “There was none of that shit happening. You’d go to Comic-Con all day and then you would go drink in the Gaslamp District, right? So this and then the next thing we did for Tron: Legacy changed all of that.”

When asked when the team first became involved with The Dark Knight, Lieu took it back even further. “So the very first thing that happened was we were talking to them about planning out what the whole campaign was going to be,” he recalled. The Dark Knight writer Jonathan Nolan had taken notice of their work through a music video and secret concert scavenger hunt they’d done for Nine Inch Nails, while director Christopher Nolan was intrigued by the idea of controlling the access fans had to finding out more about the film through a game concept built around highly coveted leaked images of Heath Ledger’s Joker character. “I think there was a picture, but it haven’t gotten out far. And they’re like, ‘We don’t want the first image of the Joker to be something like this.’”

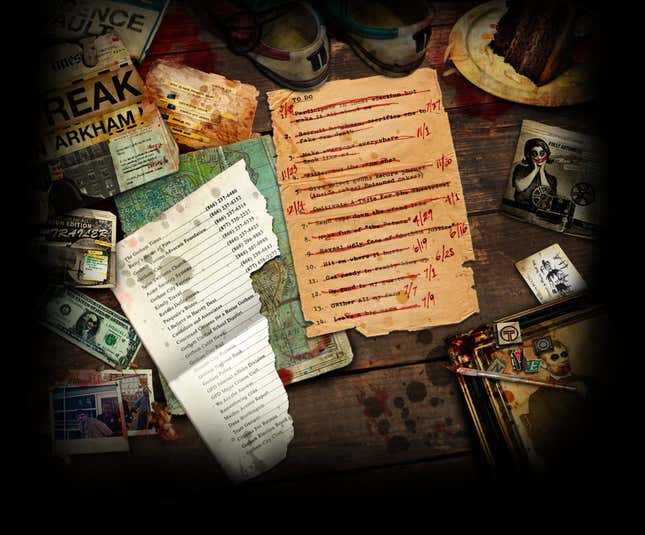

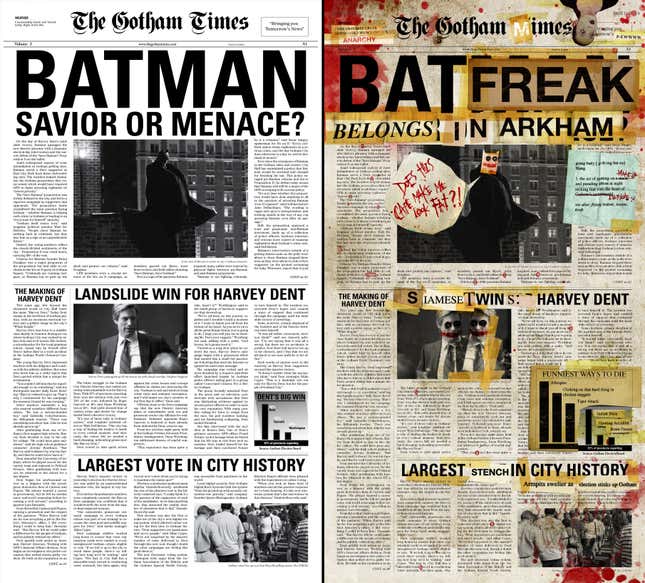

The Nolans then gave Lieu and his team the first official image of Ledger’s Joker. “That first image I remember [was] the really dark image of Heath Ledger. It’s all black except for his face with the makeup and or whatever. And they were like, ‘Help us get that out first.’” This was in the early days of film blogs joining in with the entertainment trades, and the image of Aaron Eckhart as Harvey Dent on an in-world Gotham mayoral election poster had just emerged online—so the team moved fast to start the ARG campaign.

“It was literally, like, maybe a week that we had,” Lieu said, explaining the method behind the madness they were about to unleash. “And so we went around, we bought all of the playing cards we could in town, and we pulled all the Jokers out of them and we wrote on them ‘I believe in Harvey Dent’. We flew our team out to all the top comic book stores in the country, like a dozen of them. We were literally in these stores sticking these [cards] in the new Batman comic books and not telling the stores. Places like [Los Angeles store] Meltdown Comics [which has since closed], we went in with chalk at four in the morning, literally on the streets drawing ‘Ha-Ha-Ha!’ [all over] and some body outlines—sticking cards all over there. So when they opened the store, they’re like, ‘What the hell is all this stuff?’”

Borys jumped in. “So when [anyone] got the card, it didn’t have a URL, it just said, ‘I believe in Harvey Dent too’—but if they put ‘dot com’ at the end of it, they saw the same poster, but he was tagged [like the Joker]. And then on the bottom it said, ‘Make your vote count.’” Those who found the site would be prompted to click an email form to the Joker’s inbox. “If you emailed it, you got an email back from the Joker that said, ‘Every vote counts, Here’s your X and Y coordinate’ and you plugged it in and it removed one pixel.” It was going to take 97,000 Batman fans to reveal the first official image of Heath Ledger’s Joker— and they did it in 12 hours.

Online fan communities like Batman on Film kept fans in the loop, Lieu said. “But if you’re on those forums, what you saw was that they were like, ‘Well, Christopher Nolan definitely has a vision—also because we did this, they understood and we started having the conversation of, like, they did this for us.’”

The ARG team was given unprecedented access to the film. “We were working very closely with the Nolan production team,” Lieu shared. “So not only had we read the scripts, but we were coming to them and saying, ‘Hey, here’s all the beats and here’s where it is and we’re going to go.’ And the Nolans would give feedback. We just had a very close working relationship and we got to work with them a lot and we coordinated with Warner Brothers when we could.”

When San Diego Comic-Con rolled around in 2007, they were ready to pull their Joker publicity stunt. “We told people to show up on site, but we also told them to have a friend online. We had built websites that we couldn’t really see through the mobile phones at that time. So it meant that [fans] had to have somebody online at home solving a puzzle, and they would tell people where to go on the street, and then the people on the street would get a new clue and they would get a URL, and then they would tell the people on the phone what the URL was, and when they went there, it would be a new puzzle for them to solve. And it went back and forth,” Lieu recounted of the first in-person activation.

Comic-Con wasn’t ready for them to bring in the clowns. “It was hundreds of thousands of people at home with hundreds and hundreds of people in Joker makeup. And we’re talking little boys, little girls, old men. It didn’t matter what the age was. They were just like, ‘Yes, give me the makeup,’” Borys remembered.

“Michael’s handing out Joker makeup and helping people with it. We started taking pictures of them and uploading them [onto] a site called Rent-A-Clown. So all of a sudden, the sites are filling up with all these pictures of Jokers, right? We ended up with 304 Jokers.” As their friends at home were solving the puzzle, Lieu described, “On the screen, it said, ‘look up,’ and so they told the people on the phones, their friends who were there, to look up. And that’s when it happened—they’re telling their friends, ‘Oh my God, there’s a phone number in the sky.’ But then they all had to hang up the phones with their friends.”

Borys jumped in. “So you already know that’s the taste for the theatrical, which was the very first rabbit hole—everything we do is a rabbit hole,” he said, referring to their next Gotham-related project The Arkham Asylum Files: Panic in Gotham City. The game is being touted as an escape room in a box; it shares DNA with the “Why So Serious” campaign and serves as its spiritual companion under the Infinite Rabbit Holes banner.

To the Animal Repair Shop collective, creating games with compelling stories has been where the company has impacted not just niche fan communities, but opened gateways for general audiences to come and play. Of their campaign for Tron: Legacy at San Diego Comic-Con 2010, Borys recounted, “At Kevin Flynn’s arcade we had all the games on free play. All the machines that were chosen were games that we created; Space Paranoids was the game that Kevin Flynn made which in that lore was the greatest game ever made. We made a stand up machine that every five levels would reveal a barcode that unlocked a voice from beyond— Kevin Flynn telling you things,” he said. This time, the immersive experience was done in collaboration with Disney. “Fifteen minutes into being in this place the lights would go out and flicker, the Journey song would stop, the Tron machine would move aside and you’d be let through to the End of Line club in the Grid. There was an online component with live events all over the place, and dead drops where you could go and find certain things that you could trade in for pins.”

Lieu says they do it all for the love of worldbuilding. In the age of social media, you’d imagine that element would fit in seamlessly to expand the horizons of ARGs, but that’s not always the case. “It opens as many doors as it complicates things. Social really helps from a share function and it also helps broader conversations happen in broader spaces. We first saw that when we did the Tron stuff, because a lot more people were using Facebook and Twitter. And so instead of us putting out these really obscure things that we wanted people to find, which we still did [during the] Tron scavenger hunt at Comic-Con, we were also using social [for] real-time updates, to give clues and to tell people what was happening—but it was also happening on Tron message boards and forums, just like Batman on Film. We loved it because it broadened out the audience.” he said. “At the same time, what happened is that you had some of these hardcore communities that [are such ARG people]. So the conversations were now in all these separate places, and they would kind of have to, like, intermingle to share things. For us, it’s always not been like these small, intense groups. Yes, we want those people to be excited and happy and they’re the ones who are going to go pick up your dead drops and things like that, but in order to do it at the scale that we were doing it, it would have to have people. And so social allowed those numbers to get bigger and bigger and to swell.”

He continued, sharing how it’s affected the immersive community today. “I think lately one of the challenges with social is that it’s gone the other way, where it’s gotten so refined [with] marketing and algorithms for content [directed to] specific groups that it’s much harder actually to have things have as much of an organic spread. So in one way, yes, you can do it where it’s like, TikTok, you can get millions of views on a certain piece of content, right? But the engagement following that is much less. And so now it’s much more siloed. It’s much harder even when you’re doing an ARG to even see where the conversation is happening.”

In the broader world of pop culture, that’s had an effect on things like the Disney’s now-defunct Star Wars attraction Galactic Starcruiser. The huge brand name attached and the hefty price tag it carried perhaps gave immersive entertainment the wrong image in the public eye, as something exclusive and inaccessible to the general public. “It’s a challenge now,” Lieu said. “I don’t think it’s a challenge to do ARGS and immersive cool stories—I think the scale is a challenge, and for us, we love immersive fiction and we love people playing in this space. We’ve realized, and you understand this now, that where there’s a 380-page script for The Dark Knight, there is a 1,800 page script for the ARG. The ARG wouldn’t exist without that movie. And that movie was fantastic and it was great and an iconic, all-time superhero movie. So to do the things at the scale that we’re known for, it literally cost millions of dollars.”

It’s a lot more complicated than that within the modern ARG and immersive entertainment community, with the sliding scale of free pop-up activations fueled by marketing money at SDCC for the latest pop culture product, to something like Delusion’s interactive theater shows, which cost a couple hundred dollars for a 45-minute horror production that brings you into the story. As for Animal Repair Shop’s approach, Lieu explained the team’s situation mirrors what most immersive collectives are going through. “To justify that cost, you have to get a lot of people playing. That’s one of the reasons why we’re doing physical products and games. It’s a very hard thing in today’s world to be able to pull things off at that scale and have the same impact.”

Find the The Arkham Asylum Files: Panic in Gotham City online.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about the future of Doctor Who.