In Modi 2.0, several officers occupying top administrative positions in BJP-ruled states — that is, chief secretaries — are those who worked for an extended period under the Modi government since 2014.

If Modi 1.0 was about overhauling the bureaucracy at the Centre to carry out his vision, Modi 2.0 has been about indirectly steering the administration in BJP-ruled states.

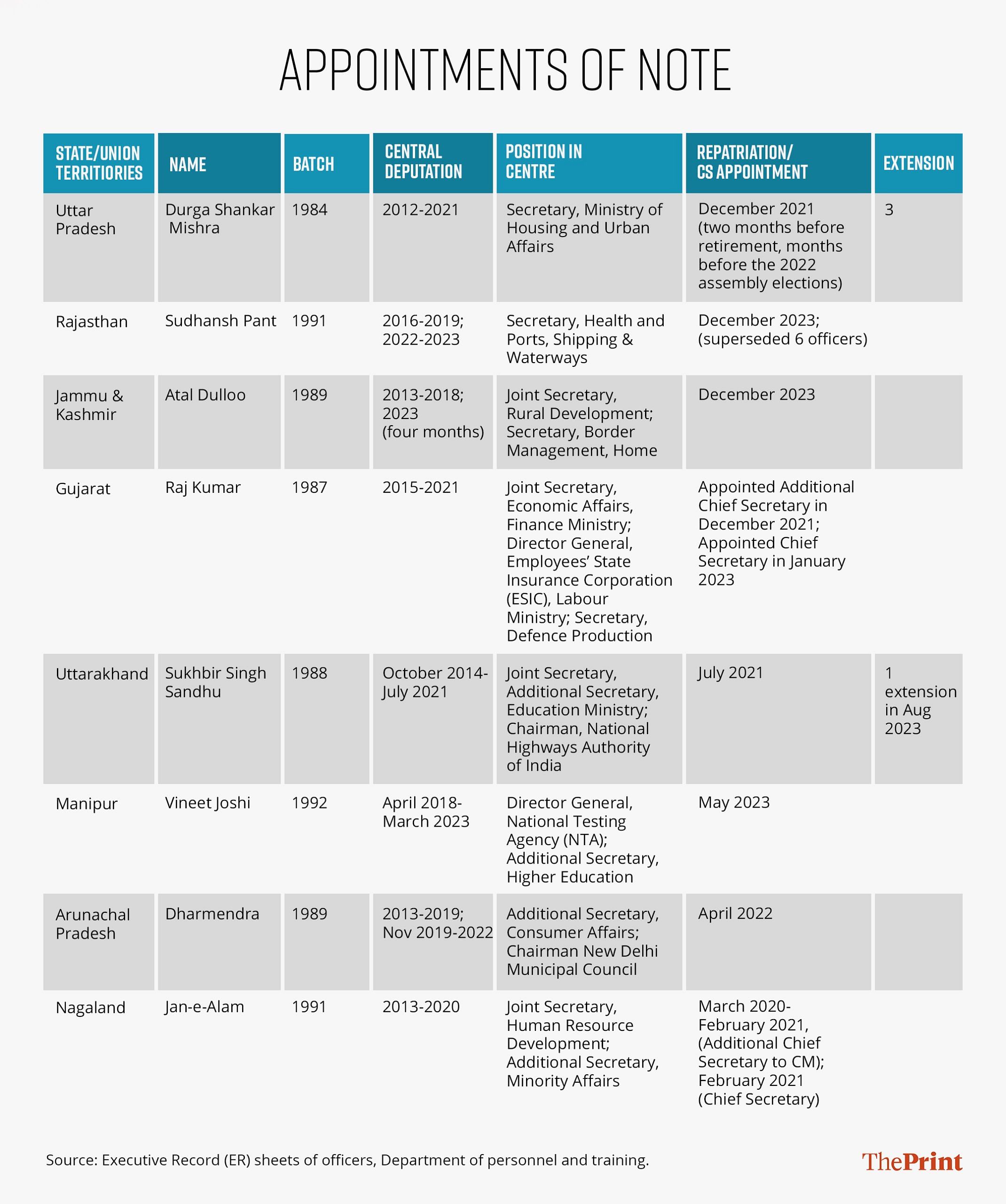

Last week, the Appointments Committee of the Cabinet (ACC), chaired by the PM, extended the tenure of Uttar Pradesh Chief Secretary Durga Shankar Mishra for the third time — two days before he was set to retire on 31 December.

Mishra, who had served as the Union secretary for urban affairs from 2017 to 2021, was given an extension days before his retirement in December 2021 and appointed the chief secretary just months ahead of the crucial assembly elections in the state in 2022.

Now, with his six-month extension, Mishra, a 1984-batch IAS officer, will remain in the top administrative post in UP during this year’s Lok Sabha elections.

Just days after Mishra’s appointment, the central government prematurely repatriated 1991-batch officer Sudhansh Pant to his home cadre Rajasthan, after which he was appointed chief secretary in the state, where the BJP came to power last month.

Pant superseded six officers who were in the running for the top post to become the chief secretary.

Before his repatriation, Pant had been serving as Union secretary and officer on special duty (OSD) in the health ministry since June 2023. He had also briefly served as OSD and secretary in the ministry of ports, shipping and waterways, headed by Nitin Gadkari, from December 2022 to June 2023.

During his earlier stint at the Centre from 2016 to 2019, after which he went back to his cadre for two years, Pant served as joint secretary in the health ministry.

The two appointments have created a buzz in bureaucratic circles.

“The two officers in question are both competent officers, so this is not a question of merit,” said an officer who retired as secretary in the central government.

“Even repatriation to state cadres is not unusual — several officers are prematurely repatriated to their cadres if the state government wants their services, even as chief secretaries…What is unusual, however, is the central government’s involvement in picking these officers and sending them back,” the retired officer told ThePrint last week.

According to convention, the appointment of a chief secretary is in the domain of the chief minister, with the central government having no say in who is appointed to the post.

While there is no breach of protocol in the appointments of Mishra and Pant, officers say the fact that these are trusted officers of the Centre is “obvious”.

The buzz now in the government is that chief secretaries in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, where the BJP has just won resounding victories, could also be picked from senior officers of the two states currently serving in the central government.

“This trend (of officers from the Centre being sent to states) has been picking up more in the second term,” said another retired officer from Uttar Pradesh who has served under both the Modi and Yogi governments.

“There is nothing technically wrong with the trend — both chief secretaries and Union secretaries have the same rank and pay scale and are eligible for either job — but these appointments do seem politically motivated,” the officer told ThePrint.

“It is obvious that the officers who have demonstrated their loyalty while working at the Centre, are being sent to handle states…It is also a function of the central government having ‘assessed’ different officers in the past 10 years, and having a bigger pool to choose from now than they did earlier,” the officer added.

Officers also point to the emergence of “two power centres” within states as a result of such appointments.

A serving officer from the West Bengal cadre, for instance, told ThePrint that the appointment of the chief secretary by the Centre sends a message to the entire state bureaucracy about a “dual power centre”.

Besides, it is bad for the morale of senior officers serving in the state governments to be superseded for the sake of officers who have come back from the Centre after several years, the officer added.

Also Read: 4 letters, 1 response — how Modi govt’s tussle with SC on judge appointments played out over 7 yrs

A steadily emerging trend

Mishra and Pant’s cases are only the most recent in this steadily emerging trend. In the second term of the Modi government, several of the chief secretaries serving in BJP-ruled states are officers who have served in New Delhi on central deputation for extended periods since 2014.

Amid the ongoing conflict in Manipur, Vineet Joshi, a 1992-batch officer heading the National Testing Agency (NTA), was repatriated to his home cadre and appointed the chief secretary in May last year.

Joshi — who replaced Rajesh Kumar who was transferred out in the wake of the ethnic clashes in the state — had served in the central government in different capacities since 2018.

The central government also appointed Tripura-cadre IPS officer Rajiv Singh as the director general of police (DGP) of Manipur, cutting short his central deputation as inspector general (IG) in the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF). Singh, a Tripura cadre officer, was sent to Manipur on inter-cadre deputation.

In December 2023, the ACC repatriated 1989-batch officer Atal Dulloo, who was serving as secretary in the department of border management in the home ministry for the past four months, to the AGMUT (Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, Mizoram and other Union territories) cadre.

He was later appointed chief secretary of Jammu and Kashmir by the Union home ministry. Previously, Dulloo has served as joint secretary in the rural development ministry at the Centre from 2013 to 2018.

Raj Kumar, an officer of the 1987 batch, who was appointed as Gujarat chief secretary in January 2023, was also serving in the central government from 2015 to 2021 in important ministries, such as finance and defence.

He was repatriated to his cadre in December 2021 as additional chief secretary two years before he was elevated to the position of chief secretary in January 2023 — weeks after a new BJP government came to power in Gujarat.

Months before the Uttarakhand elections in February 2022, Sukhbir Singh Sandhu, an officer of the 1988 batch, who was serving as the chairman of the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI), was appointed as the chief secretary in July 2021.

Sandhu had been at the Centre since 2014 and held the positions of joint and additional secretary in the human resource development (HRD) ministry before being appointed NHAI chairman.

In August 2023, Sandhu was given a six-month extension by the department of personnel and training (DoPT), reportedly due to the ongoing work in Kedarnath and Badrinath, and also to facilitate other key central government projects underway in the state.

In June 2022, Dharmendra (who goes by his first name), an officer of the 1989 batch in the AGMUT cadre went back to Arunachal Pradesh and became chief secretary of the state.

Dharmendra had been on central deputation since 2013 as additional chief secretary, consumer affairs, before he was given the all-important position of the chairman of the New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) in 2019.

In Nagaland, the current chief secretary, Jan-e-Alam, too, has served in the Modi government from 2013 to 2020 in the ministries of education and minority affairs. In March 2020, Alam was appointed as additional chief secretary to the CM, before he was elevated as chief secretary in February 2021.

While most of the aforementioned appointments are known to have the central government’s stamp of approval, there have largely been no disagreements in the choice of the officer between the Centre and state governments.

In Mizoram, however, this was not the case. In 2021, the central and state governments appointed two different officers as chief secretaries, reportedly leading to an open conflict, with Chief Minister Zoramthanga writing to Home Minister Amit Shah that the denial of his choice of chief secretary would lead to opposition parties in the state making a “mockery of his faithfulness”.

The Centre’s choice, Renu Sharma, an officer of the 1988 batch, eventually became the chief secretary. Sharma was previously serving in New Delhi.

The home ministry is the nodal ministry responsible for the transfers and appointments of officers of the AGMUT cadre, which includes Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, Mizoram and all Union territories. However, the ministry’s guidelines state that “the chief secretary and the senior most police officer in a state may be decided with the approval of the Union home minister in consultation with the chief minister of the state concerned”.

Also Read: Modi govt does U-turn on contentious 360-degree appraisal for senior civil servants — ‘no such system’

A few exceptions

There are, though, a few exceptions to this trend.

Under the governments of Manohar Lal Khattar in Haryana and former CM Shivraj Singh Chouhan in Madhya Pradesh, the chief ministers are known to have had freedom in picking their chief secretaries.

In Madhya Pradesh, for instance, Iqbal Singh Bains, an officer of the 1985 batch, was appointed chief secretary within 24 hours of the Chouhan-led BJP government returning to power in March 2020.

Known to be close to Chouhan, Bains was granted two extensions, which were subsequently cleared by the central government.

While less widespread, there were a few cases where officers serving in the central government were sent back to their cadres and appointed chief secretaries in the Modi government’s first term too.

For instance, soon after the 2017 Uttar Pradesh elections, the central government prematurely repatriated 1981 batch IAS officer, Rajive Kumar, who was serving as secretary in the shipping ministry from December 2014 to June 2017, after which he was made chief secretary.

However, by and large, chief secretaries were picked from the pool of officers serving in the states themselves. In fact, in several cases, it was some chief secretaries who were called from the states to serve at the Centre.

For instance, in the 2014-2019 period, former Odisha chief secretary J.K. Mohapatra was posted as fertiliser secretary, Punjab chief secretary Rakesh Singh was appointed secretary in the steel ministry, and West Bengal chief secretary Sanjay Mitra was appointed as road and transport secretary.

New or unusual as it may be, not all officers seem alarmed by this trend.

L.V. Subrahmanyam, former chief secretary of Andhra Pradesh, said the cases that are leading to chatter in bureaucratic circles are no more than a “lucky coincidence” of the central and the state governments wanting the same officers.

“In none of the cases can we say that the Centre has imposed its will on the state governments…If anything, it is possible that because an officer was serving in the Centre, the state government was hesitant in expressing its desire to have them back in the state,” he said.

Objectively speaking, we can see the choice of the officer concerned as either the state government’s choice or the Centre’s, “but we choose to see it as the latter,” Subrahmanyam added.

(Edited by Richa Mishra)

Also Read: Indian civil servants must shed ‘distanced and aloof’ image—the British Raj is behind us