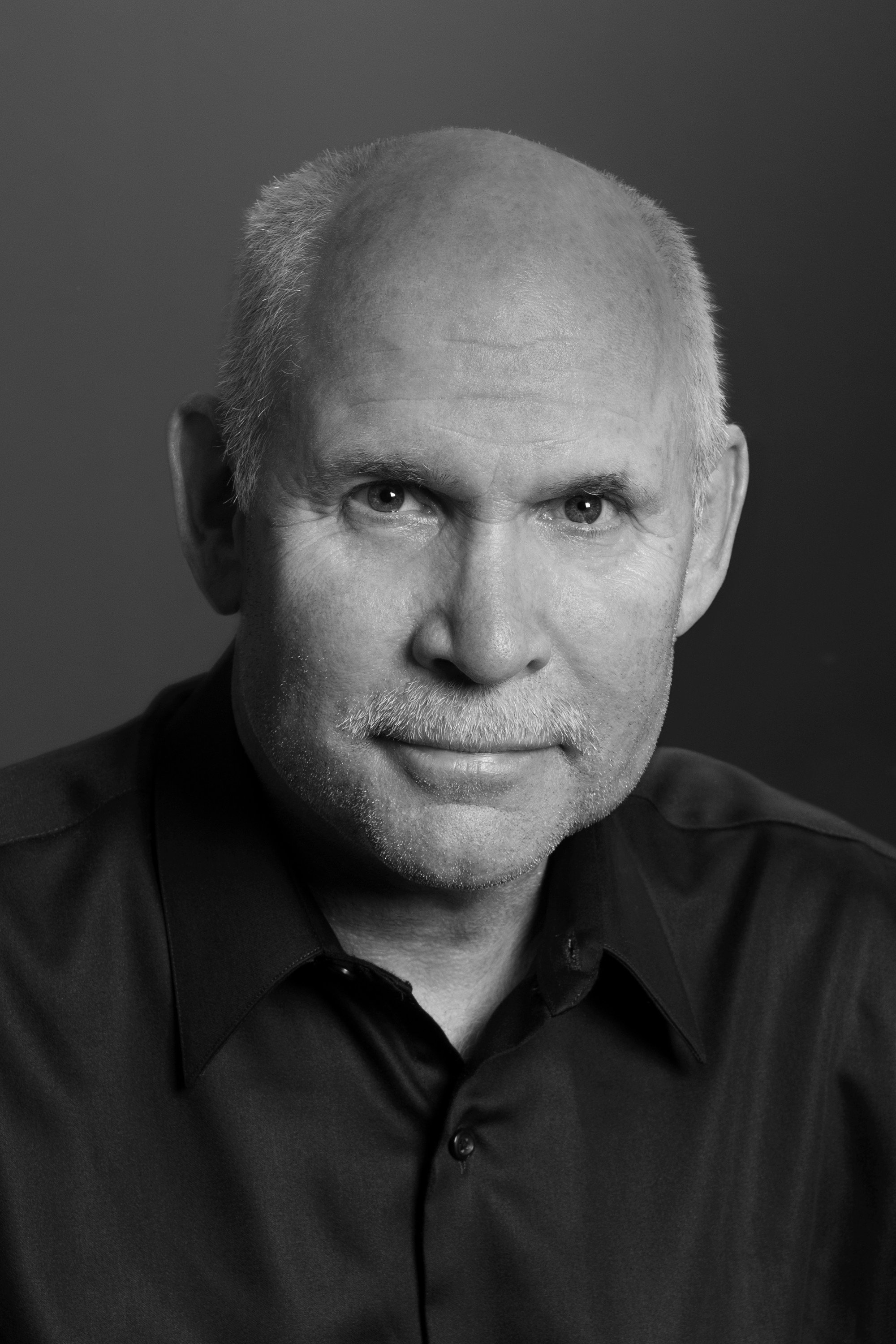

His work won him the Robert Capa Gold Medal, and his 1984 Afghan Girl portrait of Sharbat Gula, an Afghan refugee in Pakistan, which appeared on the cover of National Geographic, is one of the most famous photos of all time.

A Magnum photographer since 1986, he has been awarded the Royal Photographic Society’s Centenary Medal for Lifetime Achievement, and was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame in 2019.

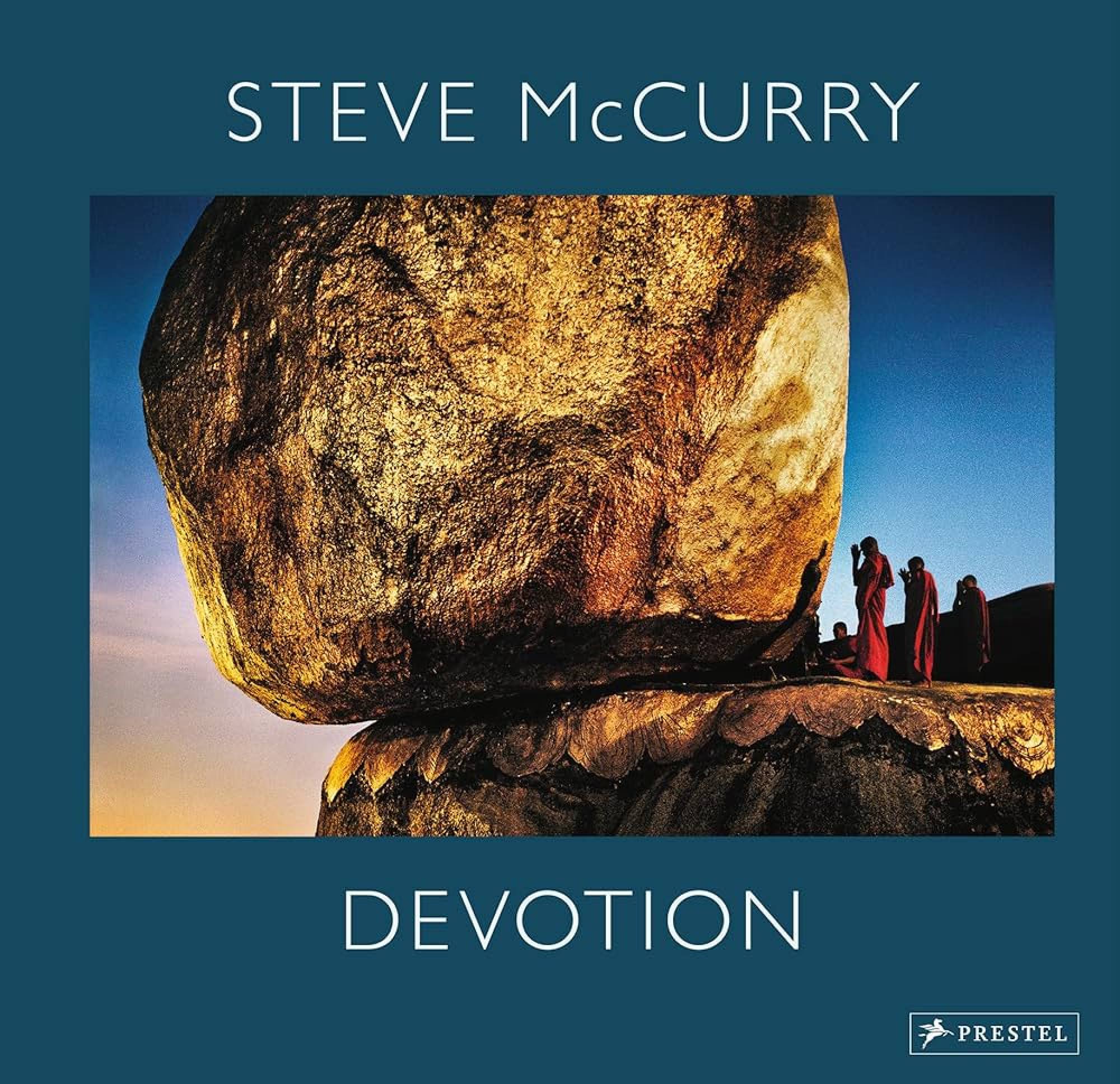

His latest book, Devotion (2023), draws from the more hopeful end of the spectrum, though, with images of prayer or quiet contemplation in the daily lives of Muslims, Christians, Buddhists, Hindus and other devotees.

But the idea of devotion is taken beyond religious faith, to include surgeons, farmers, musicians, rescue workers, carers – people dedicated to a mission, an activity or an idea. It even includes football fans.

“Devotion, for me, is about people who are dedicated, selfless and trying to achieve a great good in the world through action,” says McCurry.

With Buddhism, I see something I admire and think it’s something I’d like to achieve or attain

Steve McCurry

“It’s the best of the human spirit to try to do something that offers meaning and purpose to our lives, and to help people who are helpless or disadvantaged.”

The images were taken across the decades and around the world, from the United States to Ethiopia.

McCurry has worked extensively throughout Asia, covering pilgrims’ prostrations in Tibet, epic gatherings of humanity at festivals across India and morning prayers at the Golden Rock, in Myanmar.

He does not belong to any particular faith himself, but he has long been drawn to the principles of Buddhism.

“I don’t think of Buddhism as a religion – it’s more a practice,” he says.

If you look at people who have dedicated their lives to something, often it’s brought them peace and fulfilment

Steve McCurry

“With Buddhism, I see something I admire and think it’s something I’d like to achieve or attain. I have people close to me in my family who are deeply religious, and I respect that.

“My parents were religious. It gave them solace and comfort. Personally, my experience isn’t that. It’s great if someone wants to believe. But, for me, devotion is about compassion, empathy and selflessness.”

There’s a quote in the book from the Buddhist master and scholar Dilgo Khyentse, which says, “The stronger our devotion, the greater the blessings. But to have no devotion is like hiding oneself in a house with all the doors and shutters closed. The sunlight will never get in.”

McCurry appreciates the sentiment that a life needs a sense of purpose. “If you look at people who have dedicated their lives to something, often it’s brought them peace and fulfilment,” he says.

“That’s serious devotion: to decide it’s your mission to help other people.”

Black-and-white photography’s ‘enduring power’ in Hong Kong show

Black-and-white photography’s ‘enduring power’ in Hong Kong show

There has always been a gentle side to McCurry’s work, with recent books on subjects ranging from people’s relationships with animals to reading.

“I’m interested in human behaviour, how we are as ‘the human family’ – people playing, working, reading, sleeping, families and intimacy,” he says. “I like to see how different people are all variations on a theme.”

Devotion is certainly one of his “quietest” books. Rather than working through explosions and gunfire, McCurry often had to move silently, blending into sacred situations.

“It’s about being still and calm, confident, sensitive to the situation, and being able to move so you’re not distracting from what’s happening,” he says.

“A lot of it is to do with spending time in a place – time for them to get used to you being there. With the monk and the cat picture, for example, I spent probably three months in that area and I went back to that monastery and photographed maybe 20 times.

“I got to know the monks and they got comfortable with me. Initially, you’re like a novelty – all eyes go to you. But once you’ve slowed everything down, they understand what you’re doing and you’re no longer a novelty.

“You have to remain respectful, regardless of the situation. If you come in with guns blazing, it’s off-putting and then you become the attraction. Whereas if you take time, you become part of the scene.”

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1950, McCurry was hooked on the visual arts from an early age.

“It was captivating. I had a yearning to travel, to go to Africa, the Himalayas and other places. That was my impetus to travel: to learn about different cultures, to see places I’d read about, to actually be there and see it for myself.”

McCurry had ambitions to be a filmmaker, studying cinematography and filmmaking at Pennsylvania State University, but his interest in photography took hold.

He worked at first for newspaper The Daily Collegian, produced by students at the university, but, finding it stifling and not challenging enough, he set out for a life of photographic travel adventures.

By showing real people you can empathise with and showing what’s actually happening, people can be informed.

Steve McCurry

Five decades on, McCurry has not left challenging situations behind.

He is also concerned about the state of the planet.

“It’s sad and demoralising to think that with all the dire situations we have in this world, we’re fighting these wars, when there could be no planet if the polar caps melt.”

Aged 73, McCurry has less appetite for putting himself in harm’s way than he did as a young man, especially now that he has a family.

He continues to travel for much of the year, though, seeking out new places and returning to countries he has photographed many times to find new angles and tell new stories.

“I feel like I’ve tried to tell people’s stories and show humanity,” he says. “By showing real people you can empathise with and showing what’s actually happening, people can be informed.

“I don’t think photography in and of itself is going to change the world, but incrementally, one brick at a time, you can to try to accomplish something.”