Takasu’s posts on X have attracted more than 14 million views, the vast majority supporting his campaign to locate and detain the suspect, whose name and personal details have been published in online forums.

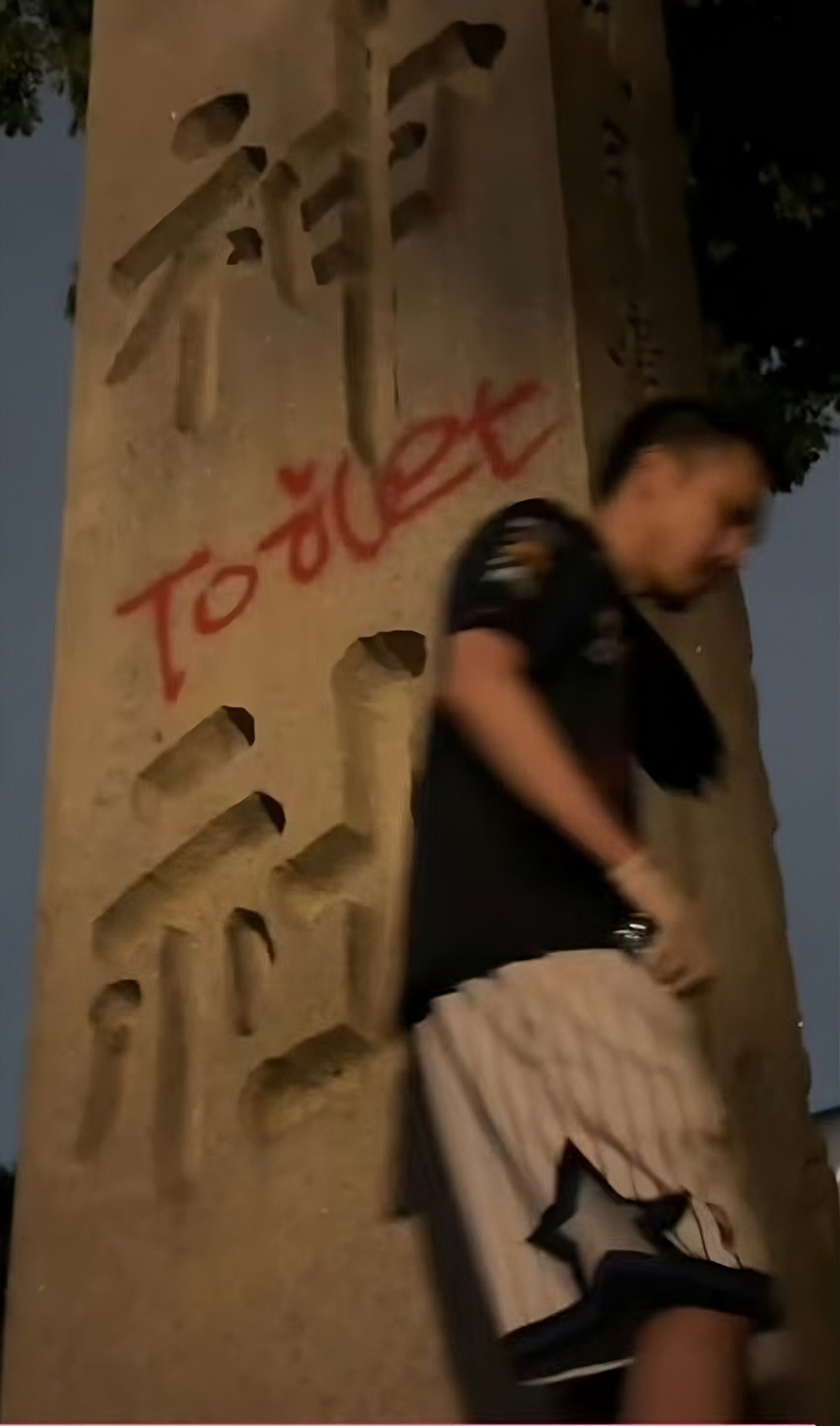

In the video, which was first posted on Chinese video sharing app Xiaohongshu on Saturday, the suspect identifies himself as “Iron Head” and says in English, “Is there nothing we can do about the Japanese government’s ocean release of contaminated water?”

Founded in 1869, the infamous shrine is dedicated to more than 2.46 million men, women and children who died in war. It is seen by Beijing and Seoul as a symbol of Japan’s past military aggression, and honours convicted war criminals among the war dead.

These includes 14 men who were tried and convicted of Class A war crimes during World War II, including General Hideki Tojo, who commanded the Kwantung Army in China and later served as prime minister, and Kenji Doihara, who headed the intelligence services in Tokyo’s puppet state of Manchukuo in northeast China in the 1930s and early 1940s.

“[China’s] Communist Party has, for decades, made a point of focusing attention on the shrine and making sure that it features prominently not only in education but also as a staple in war films and television dramas,” said James Brown, a professor of international relations specialising in Russian affairs at the Tokyo campus of Temple University. “So if you are a young person growing up in China, Yasukuni is not an issue of the dim and distant past, it’s very much part of the here and now.”

Japan is has also stood firm on the matter, he said.

“There is the argument that if the nation’s leaders wanted to show their respect to the nation’s war dead, which most would agree is fine, then they could very easily go to the nearby Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery, which is the memorial to the victims of the war and would be completely non-controversial,” Brown said.

And although Japan’s old foes insist they merely want the Class A war criminals to no longer be honoured at Yasukuni and for no politicians to make pilgrimages there, Brown says that no Japanese government could ever commit to that, given the potential domestic political fallout.

“This is an insult, and it makes me very angry,” Kato told This Week in Asia. “China should send him back because this was clearly prepared in advance, and the person who filmed his vandalism should be identified and charged.

“But it’s remarkably stupid,” he added. “Do they not realise that by urinating on a Japanese shrine and then writing graffiti on a pillar, Japanese people will reach obvious conclusions about Chinese people? Is that what Chinese people want us to think of them?”

Kato said he wasn’t optimistic that the suspect would be returned to Japan for investigation.

The incident has similarly stirred online anger, with some suggesting that Japan should close its borders to Chinese citizens.

“A decent, developed country would criticise actions like this by one of their citizens as a national disgrace and the ambassador would apologise, but this is China, so I’m sure he will be celebrated as a hero instead,” said one message on the website of online television network Abema Times.

This is not the first time that the shrine has been damaged by foreign nationals.

In 2011, a Chinese man was suspected of setting fire to one of the shrine’s gates but managed to evade arrest and returned to China. The following year, he was arrested in South Korea for an attack on the Japanese embassy in Seoul. He was sentenced to a prison term, but South Korean courts refused to extradite him to Tokyo over the earlier attack on Yasukuni Shrine.

Japanese police say they are treating the latest incident as an act of vandalism, although the perpetrator has reportedly already left Japan. The graffiti was removed by Monday morning.