The origins of paubha are unclear owing to the lack of written documentation, scholars say, with much of the tradition and techniques passed down orally.

However, a few preserved works date back to as early as the 13th century, underscoring paubha as a “devotional art practice”, according to paubha painter and researcher Renuka Gurung.

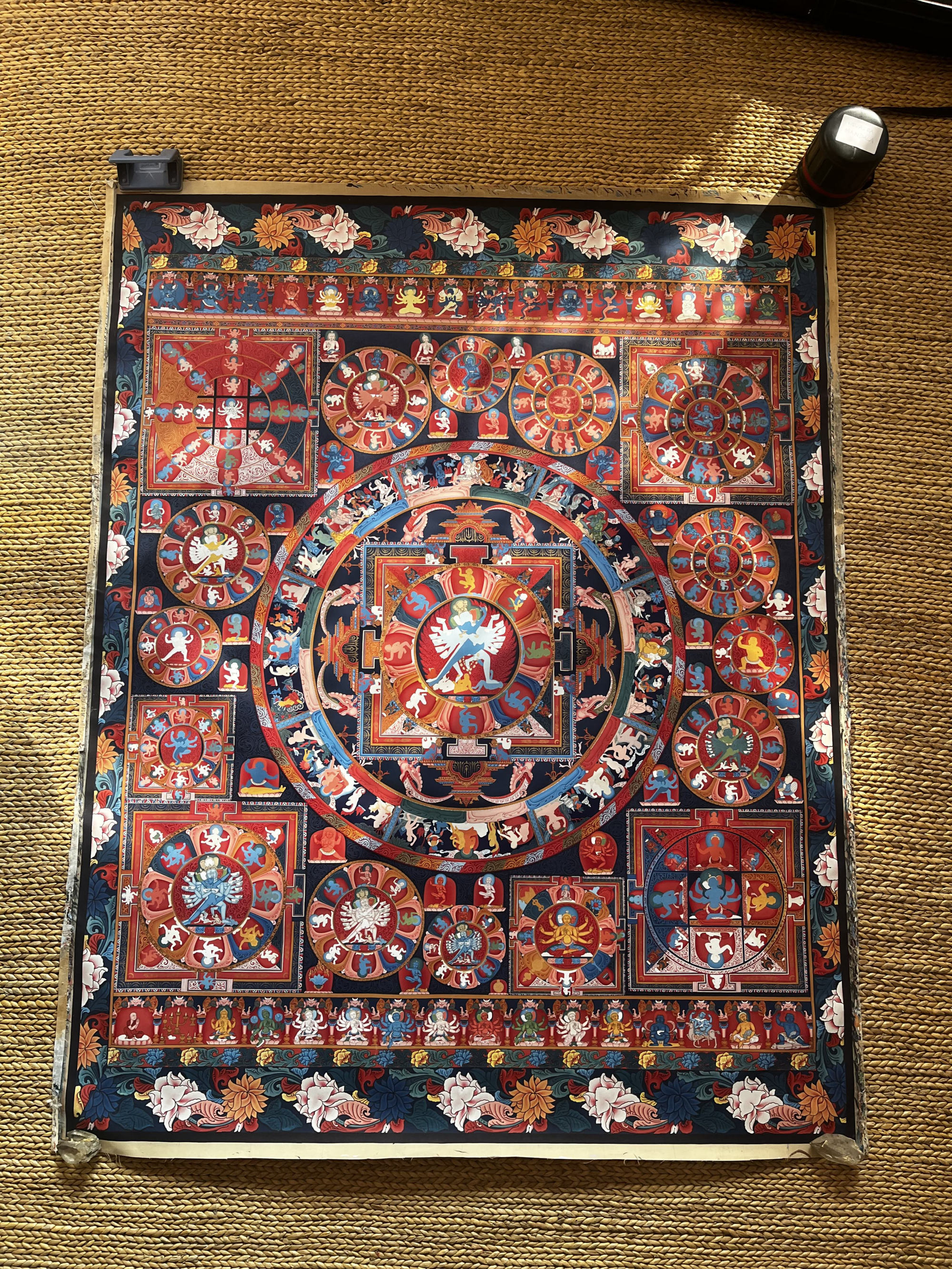

“It is a reflection of ancient Buddhist practice … it is a jewel in the crown of the art history of Nepal,” she said.

Chitrakar learned about art through his family’s involvement in religious art. Under Nepal’s feudal and hierarchical caste system, people from the Chitrakar caste – which is part of the Newar caste system, divided according to profession – were designated as painters.

When he was about 12, Chitrakar started researching iconography, deities and symbols to complete what would become his first professional work – a painting of eight mother goddesses of Hinduism known as Ashtamatrika. It was the first time he made money from his art.

Chitrakar hasn’t stopped since, and at 62 has painted dozens of paubhas. Some of his notable works – such as the Chintamani Lokeshwor, Tara and Rakta Ganesh – have taken him years to finish, given the significant time needed to research and interpret the iconography, philosophy, history and culture behind each topic.

“It is not like you study for an academic degree that you just sit for an exam after studying,” the self-taught artist said. “It is a step-by-step process, it is an experience. And once you dive into it, the layers open one by one.”

On his creative process, Chitrakar likens it to how artists translate elements, such as compassion, into their work by “trying to bring out the abstract form into art”.

While the depictions of divinity may be familiar to devout Hindus and Buddhists, how do other art connoisseurs view his paubha paintings? Chitrakar says they could be initially drawn to the explosion of colours and unpack the various layers after closer scrutiny.

“Regardless of one’s religion, when people see my art, I just want them to forget everything for a while and experience a moment of happiness,” he said. “When they get lost in it, it might spark some curiosity or make one happy. That’s my biggest achievement,” he said.

Nepal to turn Mount Everest trash into art to highlight waste blight

Nepal to turn Mount Everest trash into art to highlight waste blight

While similar to thangka art, popular in Tibet, Chitrakar says paubha is believed to be its precursor. Researchers like Gurung believe both art forms evolved from the same Buddhist spirituality philosophy, but differ in how they represent particular traditions and practices of their individual communities.

Many of Chitrakar’s artworks have been exhibited around the world, with some also in the permanent collections of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum and the Kanzoin Mandala Museum in Japan.

However, he has also done ritual paintings for monasteries and temples, which require religious initiation and fasting while working on them. These are done under strict guidance, with knowledge passed down restricted to only a few.

Asked whether such restrictions may limit the sharing of knowledge, Chitrakar says those with a certain level of mastery in paubha will be given access at the right time.

However, there may be few people who are willing to pursue paubha to that extent.

Nepal does not have paubha-related academic degrees, so those keen on learning find their way to Chitrakar’s Simirik Atelier, which he opened in 1998 to train new artists.

Rabin Maharjan, 36, came to the studio after completing university eight years ago to learn from Chitrakar. He was drawn to paubha because of its rich history and his interest in the unique art form associated with the indigenous Newar community, to which he belongs.

“It requires a lot of patience, so there’s not much interest these days,” he said. “But if you are willing to dedicate your time and work on making connections to sell your work, then there is a good future.”

He is now a professional paubha artist.

Gurung says while the number of paubha painters is in decline, growing interest in the art form in Nepal and abroad has helped keep the tradition alive so far.

It is important to introduce paubha art in the education system to help students understand the traditional practice, Gurung says, but laments that the art form is in “dire need of good masters who can pass on the true essence of paubha painting alongside the technical and artistic aspects”.

According to Chitrakar, paubha has evolved stylistically and aesthetically over the years to make it more commercially viable. Artists can add new elements as long as they retain the art form’s philosophy, which Chitrakar terms as having “freedom with discipline”.

The shift in mindset about the profession – once reserved for those from the Chitrakar caste – has also encouraged younger artists to take up paubha and Lok Chitrakar says this will ensure the continuation of the tradition, even if on a smaller scale.

“It was a country that once discriminated against creative people,” he said. “Before, people didn’t respect artists, and many believed they just sold their work to tourists. So we just saw it in a materialistic way, and we didn’t understand the value of art.”