When the KMMT project was launched in 2008, it was scheduled to be completed in 2014 but was beset by multiple issues even before the military junta deposed the country’s elected government in 2021.

Still, progress continued on the project and many segments of it have been completed. In November, Indian officials claimed it could be wrapped up by the end of 2023.

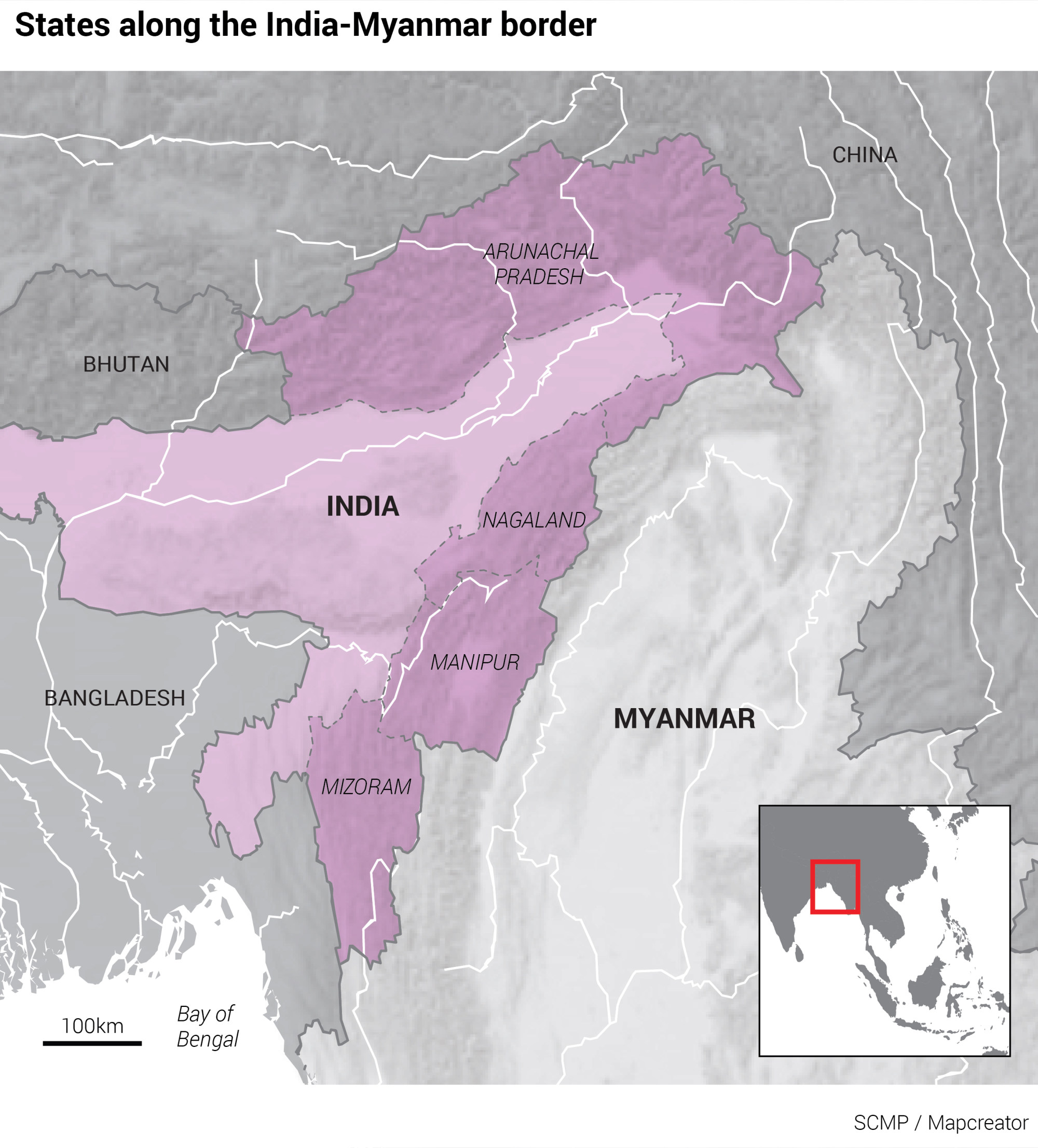

However, a crucial 109km road between Paletwa in Myanmar and Zorinpui, at the border of the Indian state of Mizoram, is yet to be completed. Given the ongoing civil war in Myanmar, the chances of work resuming on this stretch are slim.

Is India’s opposition ‘in disarray’ to challenge Narendra Modi in election?

Is India’s opposition ‘in disarray’ to challenge Narendra Modi in election?

A large area in Rakhine state and southern Chin state has already been taken over by the Arakan Army. The Indian government issued a travel advisory earlier this month, advising all Indian nationals to avoid travel to Rakhine due to the conflict.

Following the disruptions to the KMMT project, the Indian government sent a delegation across the border for talks with the rebel group.

On February 29, an Indian delegation led by Rajya Sabha (Upper House) member K. Vanlalvena from the Mizo National Front met with senior officers of the Arakan Army inside Myanmar to discuss the matter.

Joseph Lalhmingthanga Chinzah, the general secretary of the Central Young Lai Association (CYLA) of Mizoram and one of the members of the Rajya Sabha delegation, told This Week in Asia that the project had come to complete halt on the Myanmar side.

“From the Mizoram side, the project was completed in 2023 and the public is using it efficiently. However, there is no work done from across the border,” Chinzah said.

Apart from the 109km (68 mile) Paletwa-Zorinpui road, the project will also consist of a 158km inland waterway through the Kaladan River from Paletwa to the Sittwe port.

“We [the delegation] were very disappointed to see the progress of the work. With this kind of pace it will take another five years to complete the project,” Chinzah said.

It is a crucial part of India’s Act East Policy, aimed at offering the country’s landlocked northeast access to economic opportunities in the region.

Work on the project, which was proposed by India’s Ministry of External Affairs, began in 2010 and was originally slated to be completed in 2014. The estimated project cost has already escalated from 5.3 billion rupees (US$63.6 million) to 40 billion rupees (US$484 million).

“Once the road is complete, we will have access to Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore. We can export our agricultural products to these countries, which will be a huge uplift for the economy of India,” Chinzah said.

During their inspection tour, the Arakan Army took the Indian delegation to an area 15km inside Myanmar, which showed that the project’s road corridor was currently just a muddy track.

“The Arakan Army also desires for the completion of the road given their dependency for the supply of the essential commodities from across the border,” Chinzah said. Regardless of who is controlling the Myanmar side, both sides involved in the conflict need supplies from India for their survival, he added.

Indian opposition leader’s arrest sparks row with US and Germany

Indian opposition leader’s arrest sparks row with US and Germany

The KMMT project’s legal status is uncertain as the Arakan Army is a non-state actor, despite its military gains.

Gautam Mukhopadhaya, a former Indian ambassador to Myanmar, told This Week in Asia that India had to reassess Myanmar’s future.

“It seems clear that the Arakan Army and [associated] political forces – and Chin political and armed outfits – will increasingly control and govern the eastern and southern borderlands of Manipur and Mizoram,” Mukhopadhaya said, referring to an ethnic group native to Myanmar’s Chin and Rakhine states.

The project is important for Mizoram and adjacent areas to access the Bay of Bengal over the long term, especially if alternative routes via Bangladesh are unavailable, Mukhopadhaya said.

“As long as options via Bangladesh are available and the route is not economically developed, including for container traffic, its actual impact will take time,” Mukhopadhaya said.

The project is overseen by Ircon International Limited, an Indian government company that signed agreements last year with two Myanmar-based companies – Myanmar New Power Construction Limited and Su Htoo Sen – to construct different segments of the highway.

Rich in natural resources, Rakhine state’s long coastline facing the Bay of Bengal holds important strategic value for China and India.

In December, China and the junta signed a supplementary agreement to develop the Kyaukphyu port, with China’s state-owned Citic Group retaining a 70 per cent stake in the project.

“China has always had the advantage over India [with Myanmar] under military rule and that is why it was able to extract the Kyaukphyu port [project] from them. The advantages of Kyaukphyu are so great that China does not need to hinder the Kaladan project for us. India’s approach should be in line with local priorities and interests,” Mukhopadhaya said.

Despite China’s influence, Myanmar is more inclined towards India due to the shared culture and demographics between the two countries, CYLA’s Chinzah said.

“China will only do what will benefit their country. But with India, it is more of a cultural bond, which is why people relate more across the border.”