Doctors in China are reporting a startling and unexplained spike in fetuses with situs inversus, a rare congenital condition in which the organs in the chest and abdomen are arranged in a mirror image of their normal positions.

In the first seven months of 2023, the rate of fetuses identified with the condition quadrupled compared with historic rates, according to a brief report appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine Thursday.

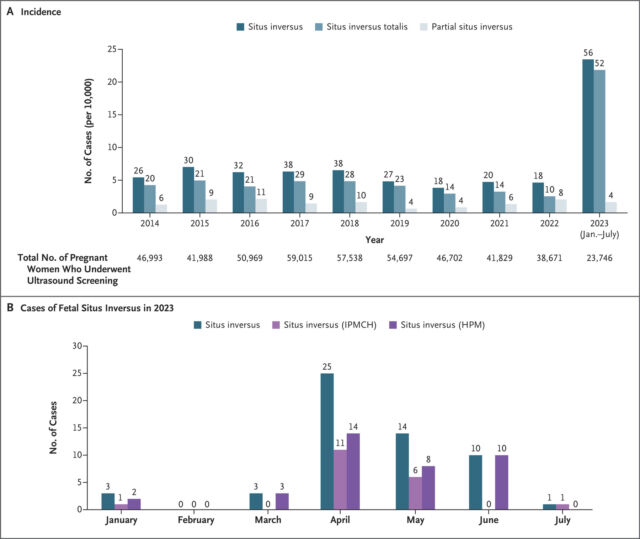

For the report, doctors from two big obstetric centers in the cities of Shanghai and Changsha combined their centers’ clinical records from January 2014 through July 2023. The doctors found that from 2014 to 2022, the yearly total of situs inversus cases was typically about five to six per 10,000 pregnant people undergoing ultrasounds. But, in 2023, the rate jumped to nearly 24 cases per 10,000 ultrasound screenings.

Looking at the 2023 cases by month, the researchers noted that the surge in situs inversus began in April and continued to June before returning to background rates in July. In all, there were 56 cases of situs inversus between January and July of 2023 among 23,746 pregnant people undergoing ultrasounds.

The ultrasounds diagnosing the condition were generally carried out between 20 and 24 weeks of gestation. The authors noted that there were no changes in the diagnostic criteria that might explain the “striking increase.”

“No conclusions”

Without supporting evidence, the doctors speculate it could be tied to a surge in COVID-19 cases, which began at the end of 2022 when China abruptly lifted its zero-COVID policy. The subsequent wave of COVID-19 ultimately infected around 82 percent of China’s population, which is over 1.4 billion people, the authors wrote. COVID-19 cases peaked at the end of December, and the wave extended into early February.

About four months after the peak in COVID-19 cases, the surge in situs inversus began. The authors speculate that the virus could have sparked the condition directly, infecting fetuses in utero, or indirectly, via maternal inflammatory responses.

But this is all highly speculative. For one thing, the report does not include data on whether pregnant people whose fetuses were diagnosed with the rare condition even had COVID-19 during their pregnancies—and how their rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with those in pregnancies without situs inversus. It also does not include data on genetic and environmental factors that are known to be linked to situs inversus. And, notably, even though cases of situs inversus quadrupled, it was still very rare overall, and no such spikes were reported in other waves of SARS-CoV-2 infections, including after the pandemic first began in China in late 2019.

As such, the authors acknowledge that “no conclusions” can be drawn from the current report as to the cause of the unusual spike. However, they call for further research to understand what was behind the uptick and the possible role of SARS-CoV-2. The good news is that most people with situs inversus have normal life spans.