Sao Paulo this year will elect 55 councillors from a field of 1,462 candidates, according to the country’s electoral court.

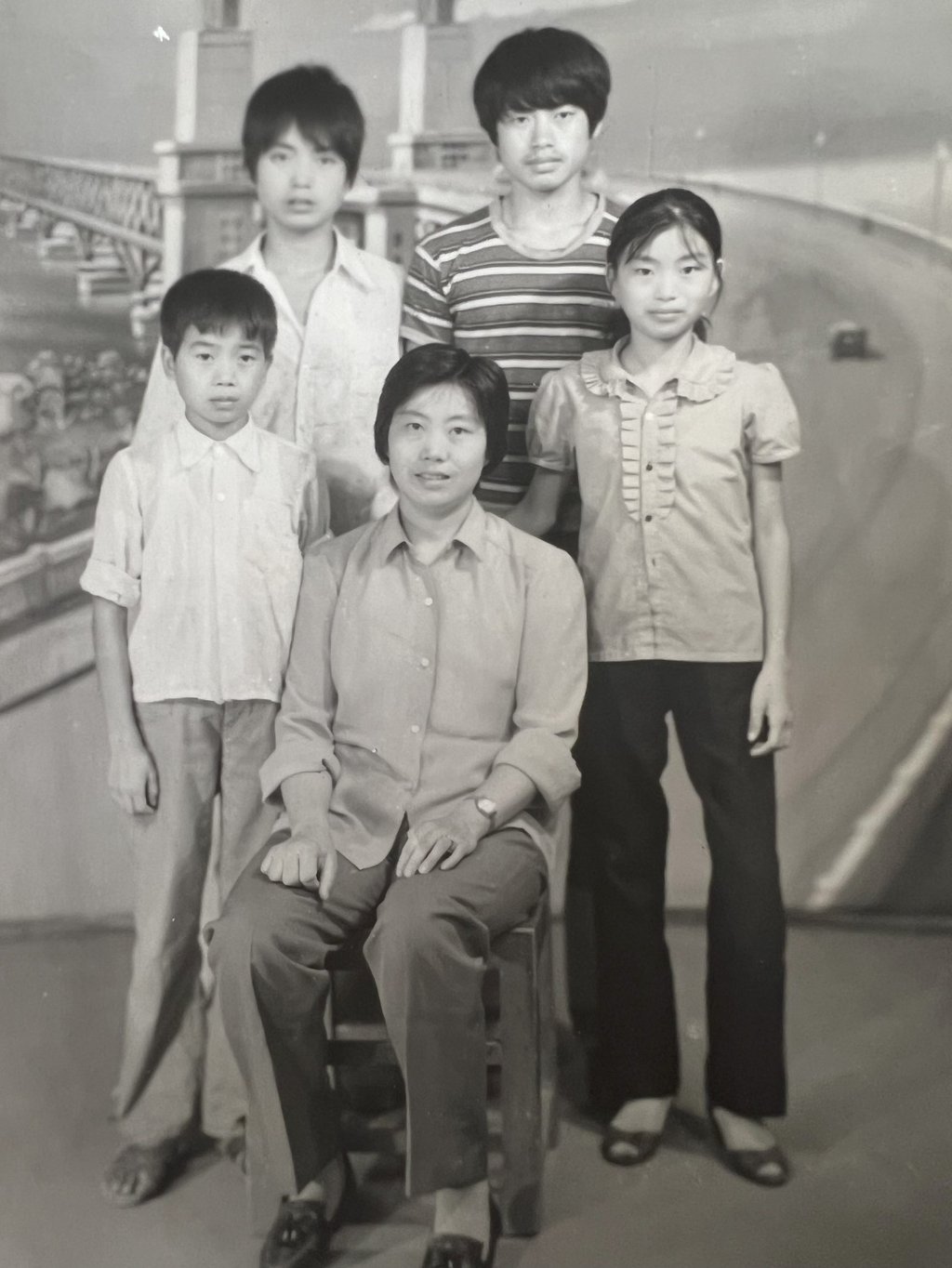

Ye, born in a village near Lishui in Zhejiang province, moved with his parents to Brazil in 1987 at the age of 10, following an uncle loyal to Chiang Kai-shek.

“We were very poor,” Ye recalled. “It was a village of 300 people. So, when my uncle came to Brazil and sent us a letter about the job opportunities here, our family saw it as a great opportunity.”

In 1998, Ye joined the Chinese Social Integration and Assistance Centre, a group in Sao Paulo helping Chinese immigrants, and in 2009, he founded the Brazilian Chinese Youth Association, which promotes group activities like sports and community service.

For all his grass-roots activity in Sao Paulo, it was not until 2022 that his ambition to formally engage in Brazilian politics ignited, Ye said, encouraged by those in the community he has served.

That said, his association with China has drawn scrutiny, some of it negative.

According to the group’s report, these outposts have disguised as support centres for the Chinese expatriate community and maintain contact with Beijing’s public security ministry to monitor political dissidents.

Local media have reported extensively on the matter, but neither the Brazilian federal police nor the country’s justice ministry has investigated the claims.

“There is nothing clandestine about it,” Ye added, saying the Chinese officers “did not come to Brazil in disguise. The last time they were here they came to discuss the signing of an extradition treaty, which I think is beneficial for both countries”.

Ye said he had only cooperated with Chinese police on two occasions and in each case to help them obtain information about fugitive criminals who had settled in Brazil. He denied that he had been asked by mainland authorities to denounce critics of Beijing.

“I think our work to support the people of Sao Paulo speaks for itself,” he explained. “I recently said at an event that, if I am elected, I will be the best example of tolerance and integration that Brazil can give in relation to the Chinese community.”

Giorgio Romano Schutte of Brazil’s Federal University of ABC said Ye could benefit from the good ties between the Brazilian metropolis and China, which counts Shanghai among its sister cities.

Ye could extend a long tradition of politicians representing Asian communities in the city, such as those of Japanese and Korean descent, he added.

“No one will vote for him because he has privileged relations with Beijing, just as no one would not vote for him because of that,” said the former deputy secretary for Sao Paulo’s international relations. “There is no such problem in Brazil.”

Meanwhile, Ye said, former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s inflammatory rhetoric against China spawned an increase in attacks on Chinese and Chinese Brazilians, something that helped spur the first-time candidate to seek elective office.

The Chinese embassy in Brasilia condemned the post, calling it “absurd, despicable and highly racist”.

Ye noted his son has experienced racism at school, subjected to remarks similar to those made by Bolsonaro government officials, and that members of the Chinese centre where he works have recounted similar stories.

Before long, the Chinese community “got together and came to the conclusion that it was time for us to get more actively involved in Brazil’s political life”, Ye said.

He deemed 2024 as the right year to run given “the Chinese community’s political maturity and the opportunity to leverage the momentum of economic cooperation between the government of Brazilian President Luis Inacio Lula da Silva and China”.

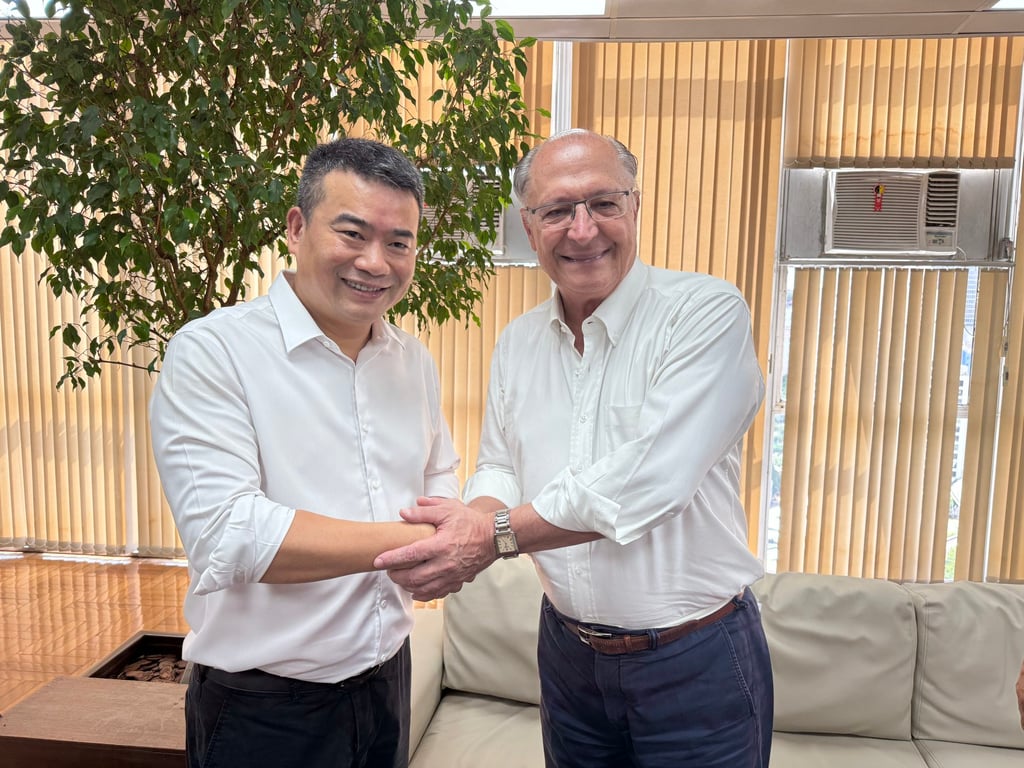

As it happens, the two countries celebrate 50 years of official relations on Thursday. And in June, Ye’s candidacy won an endorsement from Brazilian Vice-President Geraldo Alckmin.

Ye is making a concerted effort to win votes from the Chinese-descent community. But one challenge is that many such residents, despite having lived in Brazil for several years, have yet to initiate the naturalisation process to obtain citizenship owing to China’s prohibition on dual nationality.

In his quest for votes beyond the Chinese-descent community, Ye has balanced time between community work with underprivileged children and young people in Sao Paulo’s outskirts and enhancing his social-media presence.

His Instagram videos, for example, show Ye praising the Chinese economic model and pledging to adapt it to the city if elected in November. He also focuses on showcasing Chinese culture and “refuting fake news” about China.

He further aims to replicate the Chinese classroom model in Sao Paulo, enlisting educational technology from the mainland, including digital blackboards and projectors.

“I was born in China, I cannot deny my Chinese origins,” Ye said. “But I chose to live in Brazil and become Brazilian. I don’t need to fit in with the community. I’m part of it. I am raising my children here. I have a job. I pay taxes.”

“I believe I can be a bridge between Brazil and China, attracting Chinese companies to invest in Brazil, creating jobs and fostering a positive relationship.”