Why the US must engage Indonesia and Asean to restart its ‘pivot to Asia’

Why the US must engage Indonesia and Asean to restart its ‘pivot to Asia’

The pivot to Asia – aimed at strengthening everything from cooperation on climate change to regional security, trade and investment – unsurprisingly, found itself sidelined.

The difference this time may lie in the strength of alliances that the US has forged with regional partners. When Blinken claimed on November 8 that the US could maintain focus on the Indo-Pacific while simultaneously handling multiple security issues, he cited a network of allies that the Biden administration has called one of the country’s “greatest strategic assets”.

The era of absolute US primacy in Asia may be over, but the US remains capable of bringing significant capabilities to bear across multiple regions

“The era of absolute US primacy in Asia may be over,” said Alice Nason, a foreign policy and defence research associate at the University of Sydney’s United States Studies Centre. “But the US remains capable of bringing significant capabilities to bear across multiple regions.”

The “empowerment” of allies has been “the overriding priority” of the US’ Asia strategy since Biden entered office, Nason said, adding that ongoing conflicts will slow down “rather than stall” the momentum of US defence and diplomatic partnerships in the region.

Relying on friends and allies

If Washington becomes overstretched, fewer resources spent on hemming in China’s activities would mean fewer “freedom of navigation operations” and reconnaissance sorties around the country’s periphery.

Concerns about China taking advantage of an overextended US military are the reason Washington has placed so much emphasis on fostering security-cooperation initiatives in the Indo-Pacific, according to Muhammad Faizal Bin Abdul Rahman, a research fellow on regional security at the Singapore-based S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).

To deal with the prospect of a crisis in the South China Sea, Stephen Nagy, professor of politics and international studies at the International Christian University in Tokyo, said “new mini-lateral relationships” will continue to emerge, especially between the Philippines, Japan and Australia.

Optimistic that Washington has the capacity to “keep its eyes” on the region, Nagy said it was not just the US that provides a framework for stability but also its partnerships and alliances, forged through Washington’s long-standing military engagement with the region.

Japan and Australia, he said, have stepped up to create reciprocal access agreements – defence pacts between countries aimed at providing shared military training and operations – and provide infrastructure and connectivity aid to the region.

Earlier this month, Japan and the Philippines agreed to seal a reciprocal pact that would allow their troops to enter each other’s territory for joint military exercises.

We should be clear that the US does not do this alone

Japan and Australia also have a similar treaty to facilitate joint drills and strengthen security cooperation, which came into effect in August.

“[These pacts] ensure that the US understands that they are increasing their burden sharing within the partnerships,” Nagy said, noting that if crises occur both in the Taiwan Strait and on the Korean peninsula, Japan, Australia and New Zealand would be focused on the former while South Korean forces, backed up by the US, would deal with the latter.

“We should be clear that the US does not do this alone,” Nagy said.

University of Sydney’s Nason agreed that “the US relies on capable partners now more than ever to meet its regional security objectives”, adding that Washington’s sustained attention on its Indo-Pacific alliances and partnerships since the war in Ukraine began in February last year was a source of assurance.

“Competing for influence in the Indo-Pacific has been elevated as a bipartisan priority in a Congress divided in almost every other area,” she added.

Jacob Stokes, a senior fellow with the Centre for a New American Security think tank’s Indo-Pacific Security Programme who focuses on China, said Washington understood clearly that “China is not going away, far from it” and would thus not overcommit in another direction.

US neglect, shunned Muslims, extremists: Asia’s fears amid Israel-Gaza war

US neglect, shunned Muslims, extremists: Asia’s fears amid Israel-Gaza war

“While Washington staunchly supports both Ukraine and Israel, the US has not committed to fight directly on either’s behalf,” Stokes said. “That restraint stems in part from a recognition that US military power is needed in East Asia to deter aggression there.”

In addition to its growing aggression in the South China Sea, Beijing has also been carrying out military drills around Taiwan, including last Sunday, when nine of its aircraft crossed the median line in the Taiwan Strait, which serves as a de facto dividing line.

Beijing regards the island as a breakaway province to be brought under mainland control – by force, if necessary. Many countries, including the US, do not officially recognise Taiwan as an independent state but oppose the use of force to change the status quo.

A big gap to fill

Despite the dense network of US-aligned security partners around the Asia-Pacific, analysts say Washington’s diminished focus on the region will still have a big impact.

“The US does all the heavy lifting,” he said, adding that no other country was in a position to fill the gap.

Kei Koga, an associate professor in the Public Policy and Global Affairs Programme at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, said that while Japan hopes to take on greater defence roles, it is limited both constitutionally and politically – though some of these constraints have been relaxed in recent years.

However, large pockets of the Japanese public have expressed concerns about their country’s growing defence capabilities, with 80 per cent saying they were opposed to tax increases aimed at financing defence spending in a poll conducted in May by Kyodo News.

“Japan’s role will be uncertain,” Koga said, noting that Tokyo could however coordinate its policies with other allies such as Canberra and Seoul as these would contribute to the “preparation for regional contingencies”.

A long Israel-Gaza war could become a “geopolitical quagmire” for the US, RSIS’ Muhammad Faizal said, explaining that it would create doubts about whether the US and the West’s advocacy for international law and human rights were “principled or self-serving”.

“It creates diplomatic and propaganda opportunities for China and Russia,” Muhammad Faizal added, noting that Washington would find it tougher to convince the region of its Indo-Pacific strategy while sustaining its support for Ukraine.

As for Israel’s siege of Gaza, many critics have accused Western governments of failing in their responsibility to act in the face of credible accounts of war crimes being committed.

They have charged that calls for a ‘humanitarian pause’ are a distraction and an abrogation of humanitarian responsibilities, and say a ceasefire is the only way to stop the bloodshed.

Hundreds killed in Gaza hospital blast, Israel and Hamas trade blame

Hundreds killed in Gaza hospital blast, Israel and Hamas trade blame

Already – through the use of visceral, emotional, politically slanted and often false narratives – Moscow and Beijing are using their state and social media platforms to disparage Washington and undercut Israel.

Case in point: a Russian overseas news outlet, Sputnik India, quoted a military expert as saying, without evidence, that Washington had provided Israel with the rockets that hit the Al-Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza on October 17.

Poor economic engagement

US attempts at realigning Asia-Pacific partners away from China are made more difficult by Washington’s lack of economic engagement with the region, analysts say – a state of affairs that is unlikely to change given the ongoing wars, and which stands in stark contrast to Beijing’s enthusiastic investments.

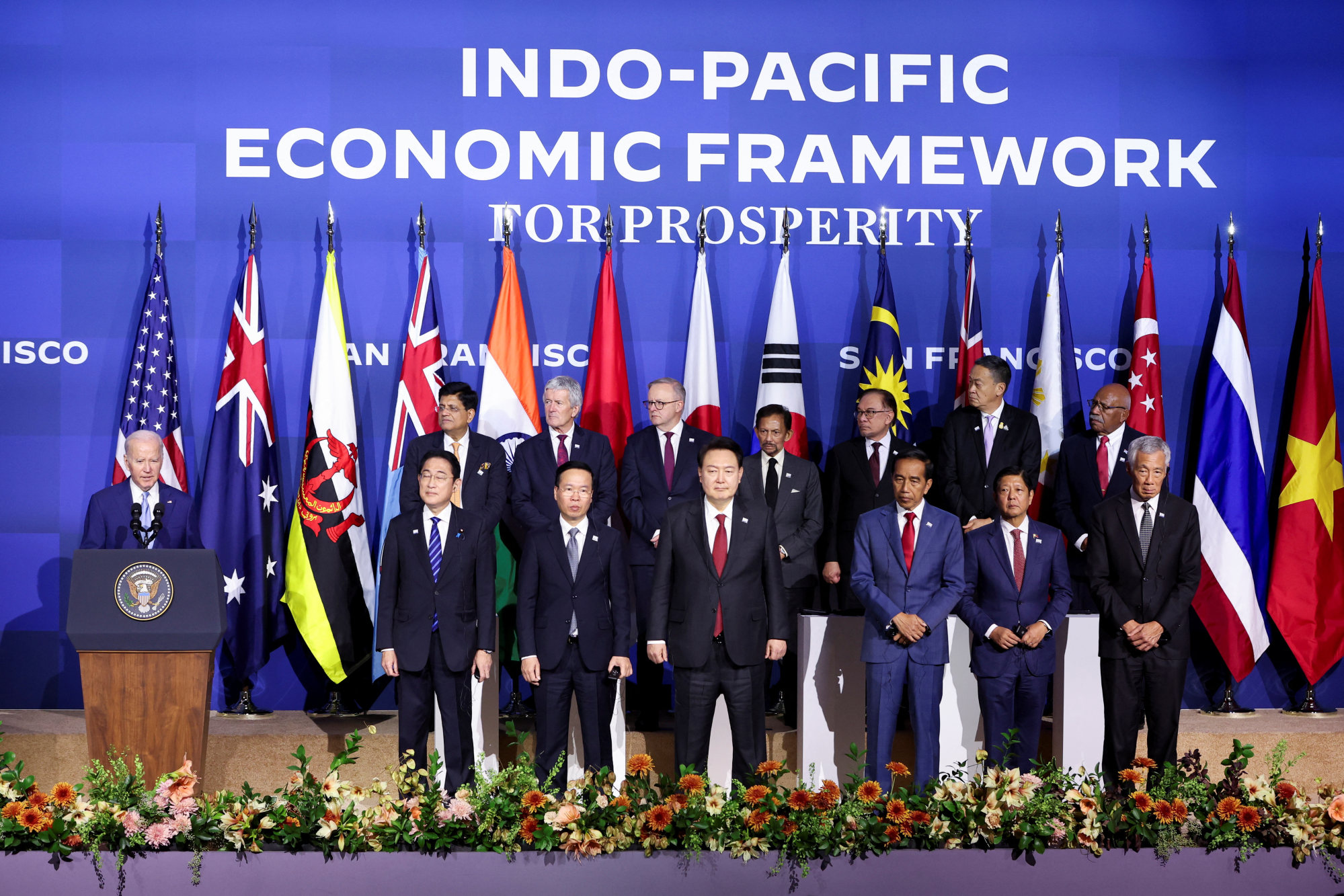

The collapse of the TPP under Trump came as a disappointment to the region and its replacement, Biden’s IPEF, does not promise the sort of trade deals and lowered tariffs that many countries were hoping for. Instead, the US says the IPEF will advance “resilience, sustainability, inclusiveness, economic growth, fairness, and competitiveness”.

Nagy said the framework was not the sort of deal that allows the US to “anchor itself into the region through concrete trade initiatives”.

“Now that these two wars have drained a large chunk of US economic resources, it will mean less investment in the region,” Anwar said.

Last year, total annual Chinese investment in belt and road infrastructure projects stood at US$67.8 billion, 34 per cent of which went to Asian countries, according to Statista, a German data-gathering platform.

In Southeast Asia, China disbursed about US$5 billion annually in development finance between 2015 and 2021, with infrastructure accounting for 75 per cent including projects in transport and storage, energy, communications, and water and sanitation.

Given the “stilted” progress of the IPEF from the outset, Nason said the US would continue “to walk on one leg in its Indo-Pacific Strategy” as it was militarily strong, but economically weak.

“It has just been announced, it will take years for it to move forward,” he said, referring to the deal signed by the governments of the US, India, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, France, Germany, Italy and the European Union.

Under the vision, a railway is expected to link ports connecting Europe, the Middle East and Asia, while facilitating the development and export of clean energy and strengthening food security and supply chains.

India’s Modi slammed for his ‘complete solidarity’ with Israel over Palestinians

India’s Modi slammed for his ‘complete solidarity’ with Israel over Palestinians

“[These] may put Muslim-majority Middle Eastern countries on a pause as to how much deeper engagement they sought to build with India,” he said.

Since the start of the war in Gaza, Modi has thrown his support behind Israel, with India abstaining from voting on a UN resolution calling for a ceasefire.