The Philippines has pinned its hopes on exports of nickel and other critical minerals to capitalise on China’s new energy bonanza and generate more revenue, and officials have made “business as usual” their mantra despite ongoing tensions in the South China Sea.

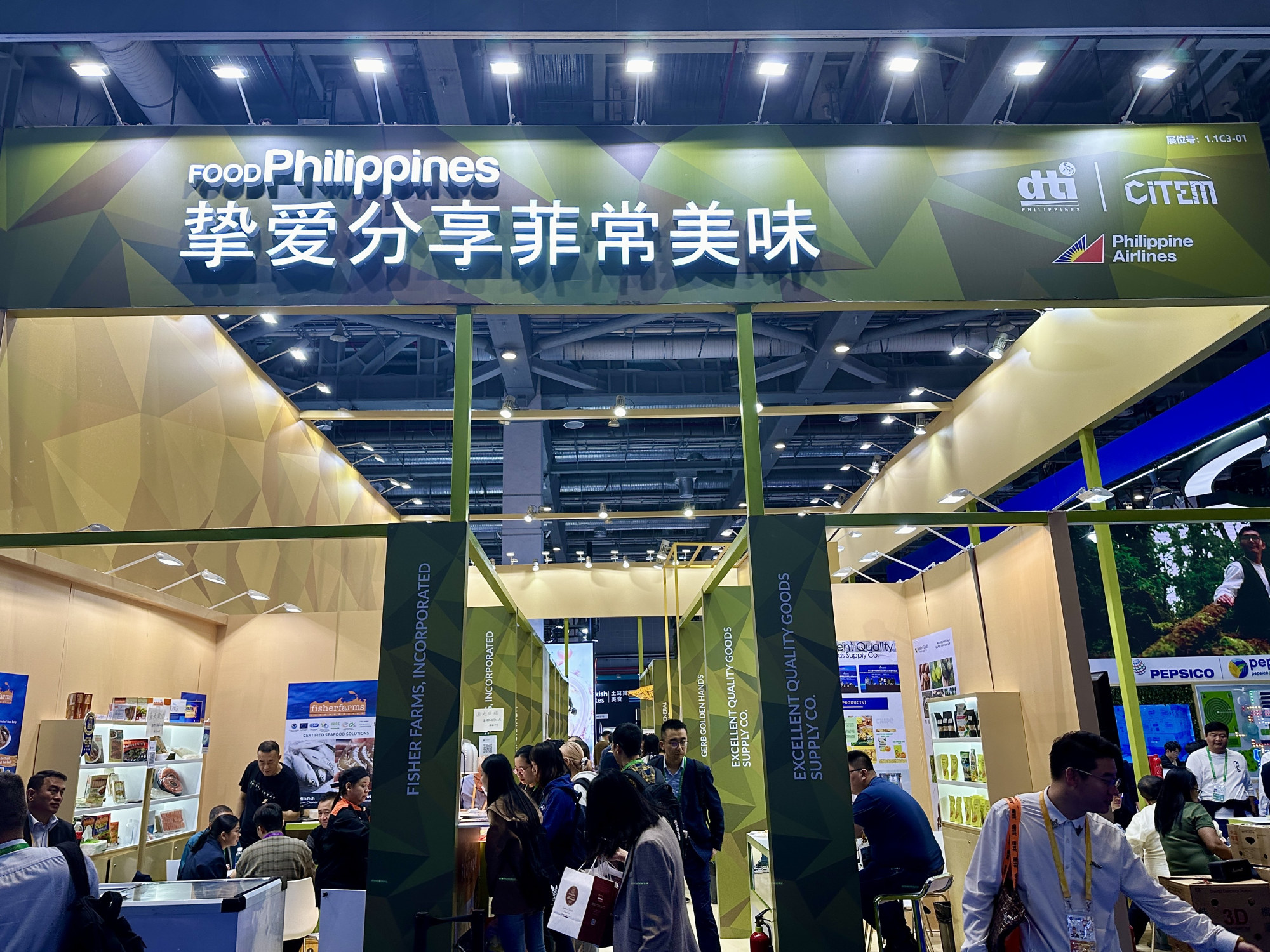

At the China International Import Expo (CIIE) in Shanghai this week, diplomats and trade representatives from Manila are redoubling their efforts to make trade with China more balanced, showing off a variety of Philippine exports from coconut to copper.

The Philippines, already a major nickel ore supplier to China, has more than 30 mines in operation. That infrastructure will go far in China, as domestic production struggles to meet ravenous demand.

Of the 5.96 million tonnes of nickel ore China imported in September, 5.52 million originated from the Philippines, according to China’s General Administration of Customs.

“We have seen a sharper focus on minerals,” said Glenn Penaranda, commercial counsellor at the Philippine consulate in Shanghai.

“The Philippines is among the top three producers of raw nickel – a key EV battery ingredient – and China is transiting to more green energy … We have deposits, capacity and we have the geographic proximity.”

His country, he added, would need more renewable energy technology and equipment from China for offshore wind farms.

China is the Philippines’ No 1 trading partner. Data from China Customs show bilateral trade in 2022 grew 7.1 per cent year on year to US$87.7 billion.

The Philippines imported US$21.7 billion worth of items from China in the first nine months of 2023, but only shipped US$8.18 billion worth of goods the other way, Philippine Statistics Authority data showed.

China’s exports to the Philippines, meanwhile, were down 14.9 per cent year on year to US$39.7 billion in the same period and the country’s imports from the Philippines were US$14.36 billion, down 19 per cent.

Ana Abejuela, agriculture counsellor at Manila’s embassy in Beijing, said food and agricultural products accounted for 10 per cent of total trade. But even in this area, the Philippines bought more from China than the other way around.

“We were so close to breaking even [in agriculture trade] in 2019, when the deficit was just US$200,000, but then Covid struck,” she said.

“For a period China basically stopped importing fruit from overseas.” The Philippines booked a US$661 million deficit in agriculture trade with China in 2022.

Penaranda did not expect the maritime clashes to affect business cooperation.

“It’s business as usual for trade between us and we are attending this (CIIE),” he said. “[Recent incidents in the South China Sea] should not stop us from doing business because it benefits both sides.”

“The Philippines and China have been trading for more than a thousand years, since China’s Tang dynasty,” Penaranda added.

“It’s deep, varied … Politics is a small part. We don’t even talk about [territorial disagreements] in business talks.”

Manila … should leave some baggage behind and focus on how much more it can gain from trade

Wang Huiyao, founder and president of the Centre for China and Globalisation think tank, said Manila must maintain a long-term vision when managing trade and territorial issues.

“While pitching business deals with China, Manila appears reluctant to fall into line on other issues like territorial disputes. But trade is distinctively complementary for both countries,” he said.

“Manila knows that too well. It should leave some baggage behind and focus on how much more it can gain from trade.”