Chinese scientists have found water molecules in lunar soil for the first time, a discovery that could be fundamental for understanding how the moon evolved and how to exploit its resources.

Samples brought back by American Apollo astronauts decades ago revealed no sign of water and led scientists to conclude that lunar soil must be completely dry, according to Nasa.

The research – carried out jointly by researchers from the Beijing National Laboratory for Condensed Matter Physics and the Institute of Physics of CAS and other domestic research institutions – was published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Astronomy on July 16.

The researchers ruled out the possibility that the water-bearing mineral was contaminated by terrestrial sources or rocket exhaust.

But one geochemist said he expected the team to find more evidence in their further study.

“If this water-bearing mineral is present in the lunar samples, more than one piece should be found,” said the scientist who asked not to be named and was not associated with the study.

The search for water on the moon has been a decades-long quest for lunar scientists.

When the United States’ Apollo mission first took humans to the moon in the 1960s, researchers had the chance to search directly for signs of water on the lunar surface.

However, initial analyses of their soil samples were disappointing and led to the prevailing notion of a “dry moon”. The prospect of lunar water was not seriously considered again for decades.

In recent years, the dry moon concept has been challenged thanks to technological advances, such as microanalysis techniques and remote sensing, according to the Nature Astronomy paper.

In 2009, for example, the Indian Space Research Organisation’s Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft detected signs of hydrated minerals in the form of oxygen and hydrogen molecules in sunlit areas of the moon.

More recently, in 2020, Nasa announced the discovery of water on the sunlit surface of the moon based on data from the airborne Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, which detected water molecules in the Clavius crater, one of the largest craters visible from Earth, in the moon’s southern hemisphere.

But the lack of returned lunar samples from high latitude and polar regions means that “neither the origin nor the actual chemical form of lunar hydrogen has been determined”, according to the Nature article.

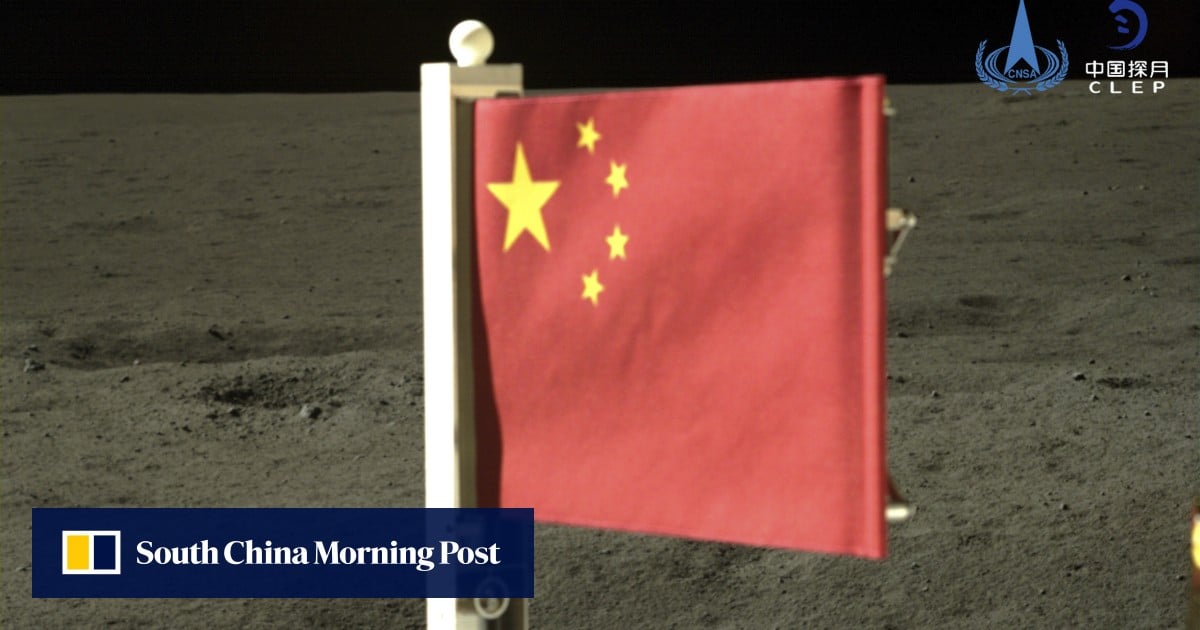

After the Chang’e-5 mission retrieved the first lunar samples in decades from the moon’s near side in 2020, researchers had a fresh chance to investigate a number of lunar mysteries – including the presence of water on the moon – because the samples were much younger than those brought back by the Apollo and Soviet Luna missions five decades ago, and from a much higher latitude.