A customer visits a supermarket in San Mateo, California, on Dec. 12, 2023.

Li Jianguo | Xinhua News Agency | Getty Images

Inflation is retreating from its pandemic-era highs.

Economic jargon yields two similar terms — “deflation” and “disinflation” — that might describe this pullback.

So, which is the U.S. experiencing? In short: Disinflation.

What is disinflation?

In an economy experiencing disinflation, prices are still rising. However, they’re growing at a slower pace than they had been.

The inflation rate is still positive but at a lower level.

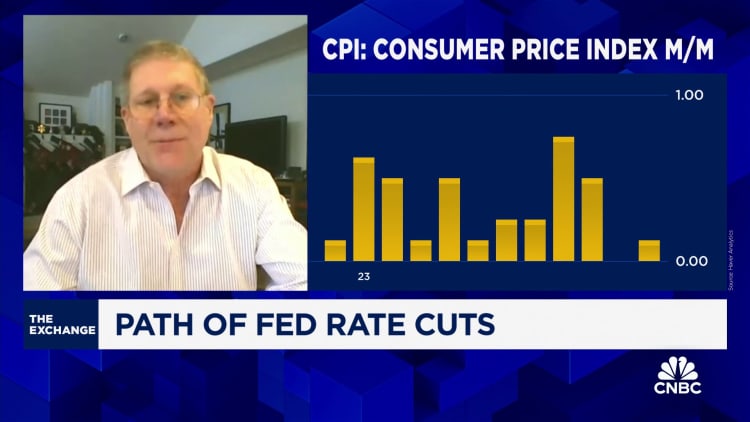

The consumer price index — a key inflation measure, which tracks average prices across a broad basket of consumer goods and services — increased 3.1% in November 2023 relative to a year earlier. That’s a significant decrease from the pandemic-era peak of 9.1% in June 2022.

“Disinflation is what we want to see right now,” said Sarah House, senior economist at Wells Fargo Economics. “It’s the more ideal outcome” relative to deflation, she said.

What is deflation?

Deflation, by contrast, is when average prices are falling outright. The inflation rate flips negative.

Some consumer categories — like used vehicles and gasoline — have deflated over the past year, according to CPI data. Their prices have declined about 4% and 9%, respectively.

However, broad, sustained deflation in the U.S. would generally be a bad outcome, economists said.

More from Personal Finance:

Why workers’ raises are smaller in 2024 — and may not go up from here

Rocky FAFSA rollout leaves millions of students, families frustrated

Tax filing season kicks off Jan. 29. Here’s what taxpayers need to know

For one, if consumers expect prices to be cheaper in the future, they may hold off on buying goods and services. Reduced consumer demand may crimp economic growth and further weaken prices, creating a self-reinforcing downward spiral.

Deflation can also cause problems for people who borrow money, economists said. The asset they own — a car or a house, say — may be falling in value while debt payments stay the same. If a borrower’s income declines, they have less money to pay down debt.

The U.S. has rarely experienced deflation

The U.S. has experienced few deflationary episodes since the Great Depression, said Andrew Hunter, deputy chief U.S. economist at Capital Economics.

“It’s something you tend to talk more about in textbooks than in practice,” Hunter said.

Historically, broad deflation has occurred in periods of “extreme economic weakness,” he said.

For example, the U.S. annual inflation rate flipped negative from March to October 2009, in the throes of the Great Recession. It nearly did so in May 2020, in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The U.S. has also seen deflation when oil prices have tumbled sharply, Hunter said. Energy prices drag down the aggregate inflation index.

That happened for several months in 2015, for example. Oil prices collapsed 70% from mid-2014 to early 2016, driven by growing oil supplies; that collapse was at the time one of the three biggest oil-price declines since World War II, according to the World Bank.

Such cases of deflation (linked to falling energy prices) can be a positive for consumers due to falling prices at the gasoline pump, for example, Hunter said.

Consumers are unlikely to see lower price tags

The U.S. Federal Reserve targets a 2% annual inflation rate over the long term.

At this “benign” rate, inflation hardly occupies consumers’ or businesses’ brain power: They generally don’t think much about costs or pricing, or how income and revenue are keeping pace with expenses, House said.

The U.S. is on its way back to that target. The supply-and-demand factors that caused inflation to surge in the pandemic era have largely unwound, economists said.

However, the Fed’s target underscores a perhaps bitter reality for consumers: Consumer price tags are unlikely to deflate (i.e., decline) much if at all for many goods and services. (Remember: Disinflation means a lower rate of price growth, not an outright price decline.)

“Consumers have woken up to the reality that prices rarely go down in the aggregate,” House said.

Of course, incomes and wages have exceeded inflation in the pandemic era, meaning the average person’s buying power has actually increased despite rising prices.

The CPI is up about 19% from November 2019 to November 2023. Average hourly earnings are up 20% over that period, while disposable personal income is up 25%.