But a lack of specialised teachers, social respect and corporate participation have stunted the growth of vocational schools, leading to an oversupply of university graduates and white-collar professionals, and a shortage of skilled technical workers, according to school principals and experts.

These include an amended law that stipulates vocational education is as important as general education, as well as detailed requirements for vocational schools to cultivate more skilled mentors and provide more on-the-job training.

China already has the world’s largest vocational education system. More than 8,700 schools enrolled around 10 million students in 2022, according to the Ministry of Education (MOE).

As a result, China is expected to face a shortage of 30 million skilled workers in the manufacturing sector by 2025, according to data from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

“When I worked in the hospital … I always felt there was an urgent need to cultivate talent that better meets the industry’s changing needs,” he said.

The former orthopaedist of traditional Chinese medicine said at the hospital more than 60 per cent of the inpatient services went to treating elderly people, and there was a skill mismatch among new workers.

Although his current school has a reputation that is “not bad”, which makes it easier to enrol students and hire staff, only about half of the teachers are “dual mentors”, meaning they have both a teacher’s licence and a qualification for the area they teach, as ordered by the government.

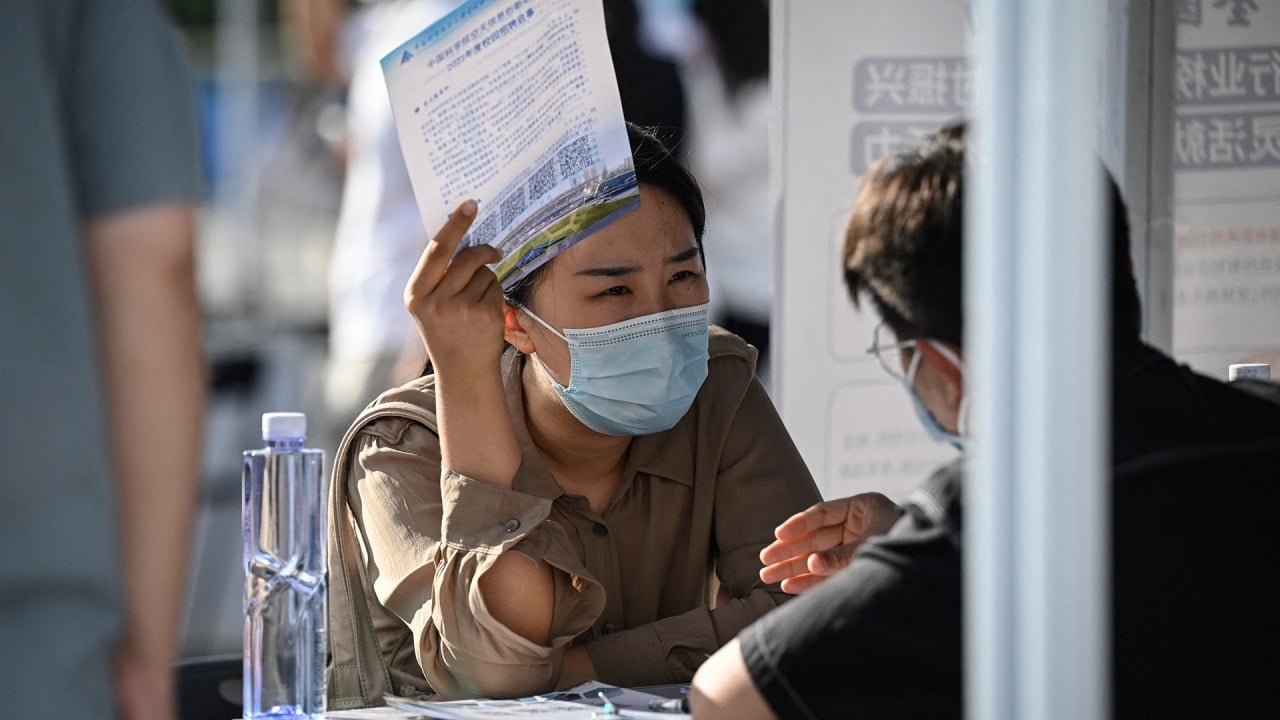

Premier calls for more blue-collar workers to plug skills shortage

Premier calls for more blue-collar workers to plug skills shortage

Quality and expertise aside, there are simply not enough teachers for vocational schools due to their low social status and low pay, said Jiang Xinhua, principal of Guangzhou City Construction College, at a seminar held by the state-run Educator magazine last month.

“In fact, the government ordered as early as 2020 that vocational schools should recruit from those who have spent at least three years in a company, but we still are not able to find such talent,” he said.

However, with just over 610,000 teachers, the higher vocational schools had roughly half the number of educators as the institutions for undergraduate courses.

The amended Vocational Education Law, which took effect from May 2022, has upgraded the status of vocational education, saying it is equally important as general education, and vocational school graduates should therefore enjoy equal education and career opportunities.

Some schools have invested big sums to upgrade their facilities amid the push.

The move “brings a workshop to the campus”, giving students practical experience, the institute’s party secretary Shao Weijun was quoted as saying.

But to many of those who have entered employment, vocational education will only thrive when graduates are decently paid.

Han Qifang, a senior technician with Chenguang Cable, a power cable producer in Zhejiang province, said workers in China were poorly paid compared to other countries.

“There is still a considerable gap between the income of Chinese blue-collar workers and those in Germany or Japan,” he said.

And while Han is an award-winning and somewhat influential figure, he said rewards and cash incentives from the government still often ended up in the accounts of his employer.

The government has rolled out various projects to encourage businesses to support craftsmanship, he said.

“[But employers] tend to think that they have paid the outstanding technicians, even at a higher level than ordinary employees,” he said. “So they’re unlikely to volunteer to share the government funds with the technicians.”

Can China’s ‘out of touch’ vocational system fill blue-collar void?

Can China’s ‘out of touch’ vocational system fill blue-collar void?

In 2022, the average monthly income of fresh graduates with vocational education degrees in China was 4,595 yuan (US$643), compared with 5,990 yuan for those with bachelor’s degrees, according to a survey by Beijing-based education consulting firm MyCos.

Han added that because of the low pay for blue-collar workers, the worst performing students ended up going to vocational schools, leading to a negative social perception of vocational education.

Under the existing education system, all students sit two major exams, known as the zhongkao and gaokao, before being admitted to a traditional secondary school and university respectively. Those whose scores are not high enough either end up in a vocational school or enter the job market, feeding into the negative stereotype.

There have been news reports about some vocational schools offering fake majors to attract students who hope to enter new professions. Many companies have been accused of exploiting students by making deals with vocational schools to recruit “interns” and pay them below minimum wage.

As part of the reform to this education segment, authorities have encouraged corporate engagement to improve vocational training and have vowed to build more than 10,000 companies that also function as training centres in partnership with vocational schools.

But most companies have shown little interest due to the high cost of training, according to a human resources manager at an advanced material manufacturer in Dongguan, Guangdong province.

“It takes at least half a year to train a beginner from school, while it’s easy to find experienced workers directly in the job market. So small and medium companies won’t be very keen to work with schools,” said the manager, who gave his surname as Liang

“It is more of an assignment for industry leaders, which have a heavier burden in fulfilling social responsibility,” Liang said.

Ye Senlin, who owns a biotechnology company in Zhejiang province, was not enthusiastic about collaborating with vocational schools either, especially during an economic downturn when there are plenty of choices in the labour market.

“So many companies have shut down and there are people looking for work everywhere,” he said.

China’s urban unemployment rate hit a peak of 5.6 per cent in February 2023 and stood at 5 per cent as of November, according to the latest data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

But the jobless rate for the 16-24 age group had climbed to an all-time high of 21.3 per cent in June of last year before the NBS stopped releasing the figures on the grounds that the statistics needed to be “further improved and optimised”.

“Fresh graduates may be able to take some office work, but not really when it comes to manual labour,” he said. “To be frank, few vocational school graduates live up to our expectations when they’re hired as frontline workers.”