India counts 8.6 per cent of its 1.4 billion population as a tribal demographic – with their own indigenous culture, food, clothing and lifestyle. The government and private agencies intend to ride on such uniqueness from this segment in the name of tribal or eco-tourism.

Although the national strategy of eco-tourism calls for involvement of local communities before any protected or pristine area is identified for the purpose, this rule is often not followed, critics say.

One such project is a grand US$9 billion scheme by the Indian government, under which New Delhi plans to create its own “Hong Kong” on land occupied by some 240 indigenous Shompen tribespeople in the Greater Nicobar Island of Andaman and Nicobar archipelago. There are plans to build a mega-port, city, international airport, power station, defence base and industrial estate in the area.

In India, a remote island tribe risks losing its voice and cultural identity

In India, a remote island tribe risks losing its voice and cultural identity

Nearly 40 international scholars have slammed the move as “genocide” of the Shompen tribe, who are nomadic hunter-gatherers. The academics have urged Indian president Droupadi Murmu to pressure the government to halt the project.

A former senior tribal welfare department official, who worked with aboriginals in the archipelago for more than three decades, told This Week in Asia on condition of anonymity that the development would destroy natural resources and leave the Shompens in the lurch.

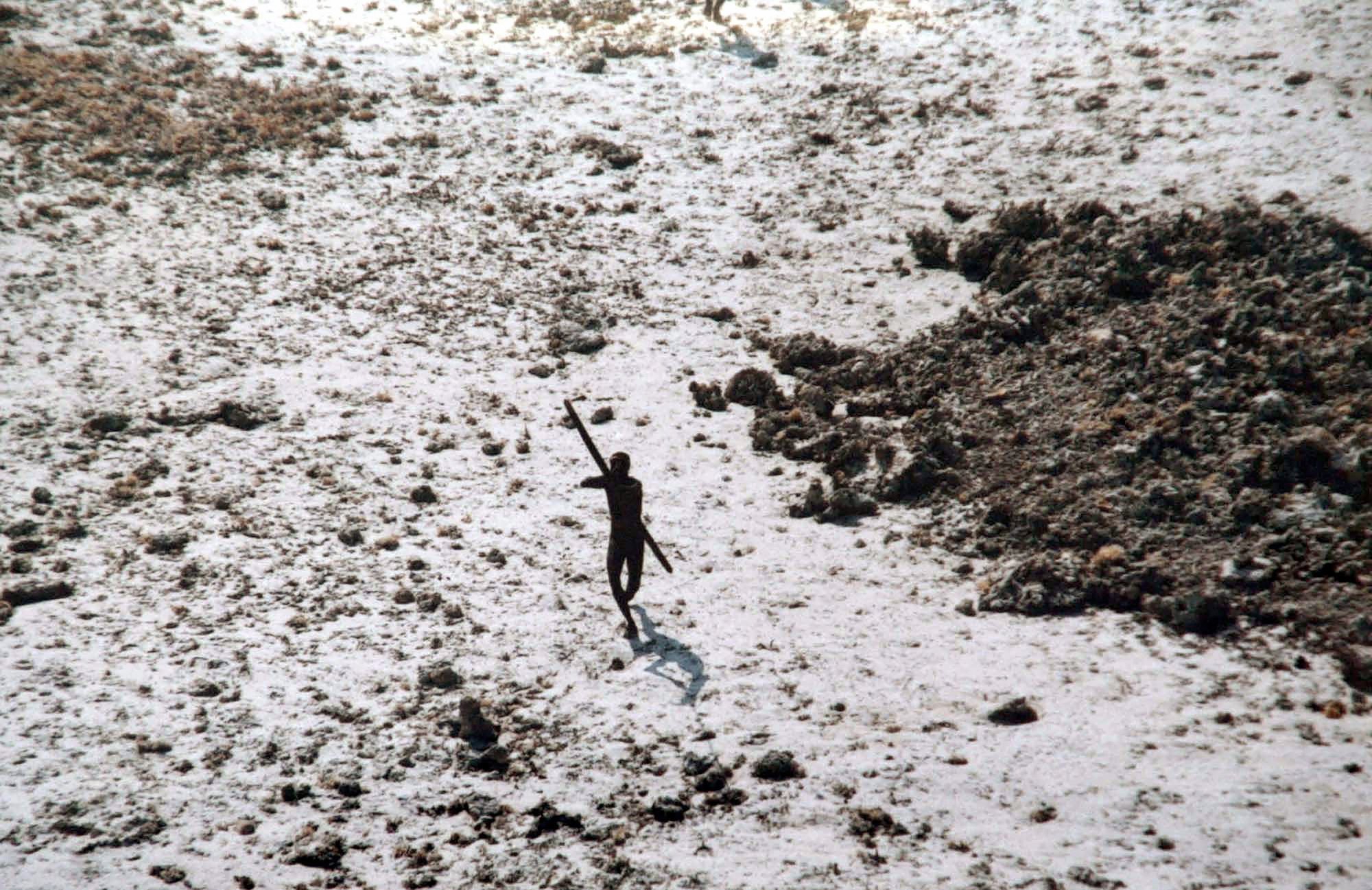

The indigenous Jarawa tribe’s existence is already under threat from the construction of a highway cutting through their habitat in the archipelago, as tourist buses often stop to watch them “naked” or offer them spicy food, thus making them vulnerable to diseases.

Lack of respect

Tribal tourism has been expanding in most Indian states at lightning speed.

Of the 62 tribes in Odisha, tourists travel to see 13 particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs) including the rustic Bonda women, who wear multicoloured beads, and Dongria Kondh men, who sport aluminium neck rings, beads and coin necklaces.

In 2012, following the abduction of two Italian tourists by Maoists in the tribal belt of Daringbadi, the government banned foreign tourists in PVTG areas and slapped a three-year prohibition on photography and videography of tribal groups.

The restrictions were lifted in 2016.

Now, the government invites “nature tourists” to experience wild landscapes sustainably, through camping, stay in eco-resorts, trekking and boating.

Benjamine Simon started tribal tourism in Odisha’s various districts such as Kalahandi, Kandhamal, Jeypore, Mayurbhanj and Koraput in 1977 to provide an opportunity for outsiders to learn about the tribes’ rich cultural heritage, housing and food habits through visits to local weekly markets and certain areas permitted by local communities.

Simon is disappointed at how tourism is managed now, with rampant use of plastic bottles and packaged food.

“Many people have jumped into the tourism business without understanding that respect towards tribal people is key,” warned Simon, founder of destination management company Travel Link.

India’s last tribe of literal headhunters mourn the passing of ‘simpler times’

India’s last tribe of literal headhunters mourn the passing of ‘simpler times’

“When tourists visit a tribal village, they must give back to the community by planting a tree, promoting local art and craft and maintaining an eco-friendly travel approach.”

Bhubaneswar-based independent forest and tribal rights researcher Tushar Dash said eco-tourism was promoted in several forested areas, such as the Simlipal Tiger reserve in Mayurbhanj district inhabited by particularly vulnerable tribal groups – Mankidia, Lodha and Kharia.

Such action, however, impinged on the habitat rights of tribes protected under India’s Forest Rights Act.

Rampant construction of tourist accommodation in these areas and frequent movement of tourism vehicles are destroying “critical biodiversity and ecology”, according to Dash.

“They are as destructive as any infrastructure and highway projects, since both aim to take away the land and resources of tribals,” Dash added. “Tribals hardly get any benefit from tourism.”

Siliguri-based social activist Soumitra Ghosh said the forest and tea garden-dominated areas in the northern region of West Bengal had been plagued by “unregulated” and “unrestricted” eco-tourism.

He added that the government should clearly state the number of resorts or homestays to be constructed and the stakes tribespeople should hold in the tourism business, as well as annual limits on tourist footfall.

But businessmen in connivance with local politicians had been taking away tribal land by making them sign dubious documents or giving them very little money in exchange, Ghosh claimed. “It defaces the history of the landscape and culture while tribals remain mute spectators.”

In the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, the government invested 992 million Indian rupees (US$11 million) to develop a tribal circuit covering Jashpur, Kunkuri and Mainpat, and other parts of the northern region.

But in 2023, India’s supreme audit institution reported a series of drawbacks in the project such as a lack of proper criteria for the selection of destinations, a failure to attract tourists in the previous two years in the tribal craft hub, a lack of drinking water, water supply to the toilets and telephone connection, and a failure to enable local craftsmen to practice crafts at artisans’ centres in these destinations.

Social activist Alok Shukla said that roads are constructed and widened in the Maoist stronghold of Abujmarh in southern Chhattisgarh, which the locals suspect to be the first steps to inviting tourism and mining.

Adding that homestays and resorts had been constructed in other parts of the southern region, Jagdalpur-based tribal rights activist Anubhav Shori, from the Gond tribe, said government agencies, settler businessmen and middlemen reaped all the profits in tribal tourism by exploiting natural and cultural resources, while the locals were made to dance and cook for tourists with no ownership in the project.

To protest against such exploitative projects, 650 people from the Dhurwa tribe of Dhurmaras and Tiriya villages started sustainable eco-tourism two years ago by offering bamboo rafting and kayaking services to about 40 tourists daily, earning about 30,000 to 65,000 Indian rupees (US$360 to US$780) a month.

“They have taken ownership of their own resources by implementing ecological sustainability and self-governance,” Shori said. “Plus, the villagers don’t allow use of plastic and polythene to maintain the ecological balance.”

At Amadubi village of 1,000 tribal members in the eastern Jharkhand state, tourists pay to sample local food such as sorey (porridge) and ledo (a type of biryani with meat and rice), watch tribal dances and interact with local artists.

But Amitava Ghosh, secretary of non-profit Kalamandir, which facilitates the tour, said the locals had set clear rules that they should not be displaced, no trees would be cut and no more than 10 tourists would arrive at set times. Large crowds are allowed to enter the village only during tribal festivals.

“It is important for tourists and the government to understand that self-esteem and respect of tribals cannot be compromised in the name of tourism,” Ghosh said. “Ethics is key in tourism.”