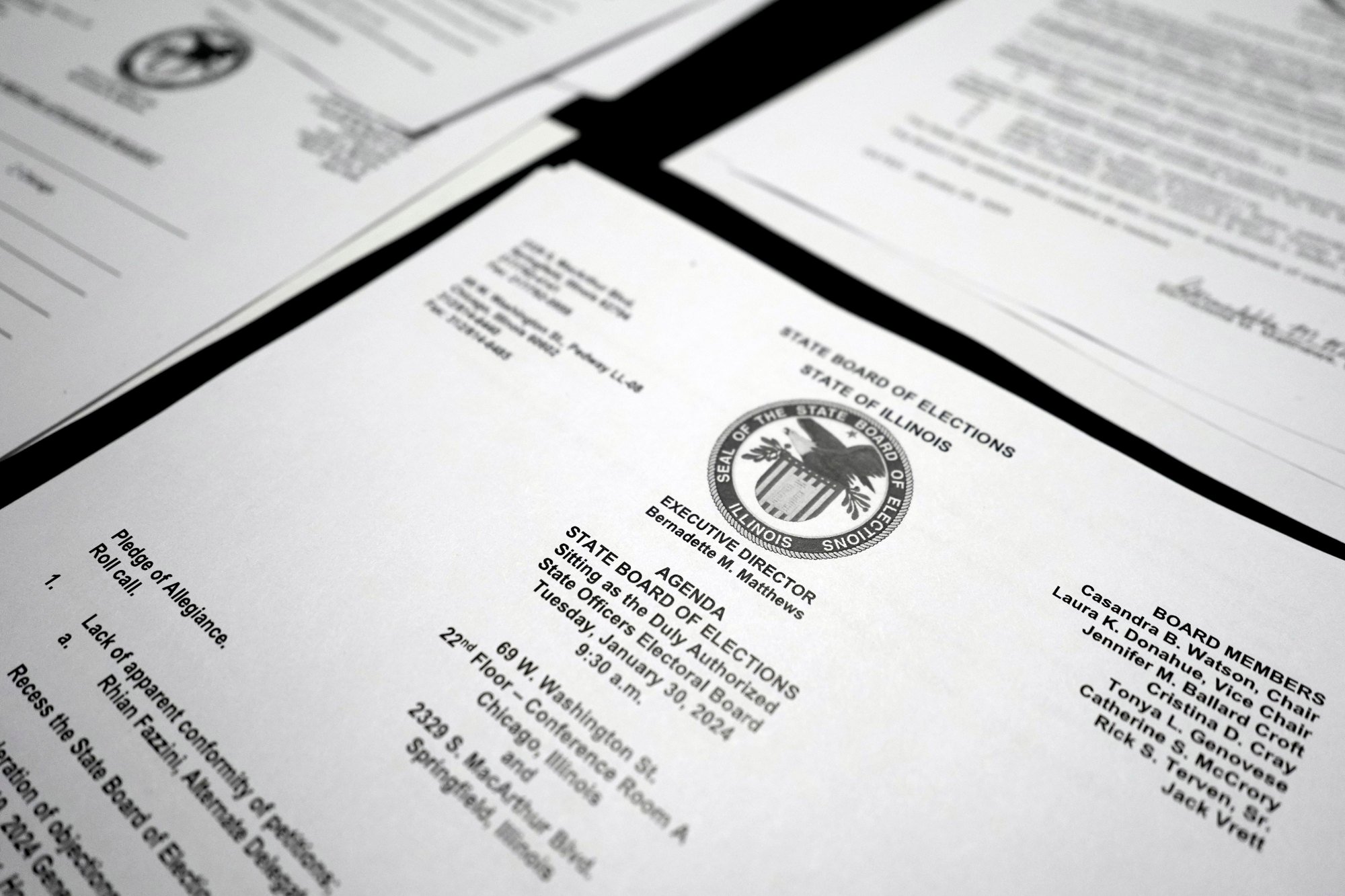

The eight-member board, composed of four Democrats and four Republicans, agreed with a recommendation from its lawyer to let Trump – the front runner in the Republican primary – remain on the ballot by determining it did not have the authority to determine whether he violated the US Constitution.

Board member Catherine McCrory prefaced her vote with a statement: “I want it to be clear that this Republican believes that there was an insurrection on January 6. There’s no doubt in my mind that he manipulated, instigated, aided and abetted an insurrection on January 6.”

But McCrory said she agreed the board does not have jurisdiction to enforce that conclusion.

Trump’s lawyer urged the board not to get involved, contending the former president never engaged in insurrection but that was not something it could determine. “We would recommend and urge the board to not wade into this,” lawyer Adam Merrill said.

Trump cheered the decision in a post on his social media network, Truth Social: “The VOTE was 8-0 in favor of keeping your favorite President (ME!), on the Ballot,” he wrote.

Trump could lose his business empire in New York. Here’s why it would be a first

Trump could lose his business empire in New York. Here’s why it would be a first

A lawyer for the voters who objected to Trump’s presence on the ballot said they would appeal to Cook County circuit court.

“What’s happened here is an avoidance of a hot potato issue,” lawyer Matthew Piers told reporters after the hearing. “I get the desire to do it, but the law doesn’t allow you to duck.”

The issue is likely to be decided at a higher court, with the US Supreme Court scheduled next week to hear arguments in Trump’s appeal of a Colorado ruling declaring him ineligible for the presidency in that state.

The nation’s highest court has never ruled on a case involving Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which was adopted in 1868 to prevent former Confederates from returning to office after the Civil War but has rarely been used since then.

Some legal scholars say the clause applies to Trump for his role in trying to overturn the 2020 presidential election and encouraging his backers to storm the US Capitol after he lost to Democrat Joe Biden.

Dozens of cases have been filed around the country seeking to bar Trump from the presidency under Section 3. The Colorado case is the only one that succeeded in court. Most other courts and election officials have ducked the issue on similar grounds to Illinois, contending they do not have jurisdiction to rule on the obscure constitutional issue.

Maine’s Democratic secretary of state also ruled that Trump violated the 14th Amendment and is no longer eligible for the White House, but her ruling is on hold until the Supreme Court issues a decision.

Trump’s critics argue he’s disqualified by the plain language of Section 3, which forbids those who swore an oath to “support” the Constitution, then “engaged in insurrection” against it from holding office. They contend the former president is ineligible just as if he did not meet the constitutional threshold of being at least 35 years old.

Maine becomes second state to bar Trump from presidential primary

Maine becomes second state to bar Trump from presidential primary

But Trump’s lawyers have argued that the provision is vague and unclear and that January 6 does not meet the legal definition of an insurrection.

Even if it did, they argue that Trump was simply exercising his First Amendment rights and is not liable for what occurred, and that the ban on holding office should not apply to presidents.

Though Trump has blamed Biden for the lawsuits because several have been filed by liberal non-profit groups, there is no evidence the president was involved.

On Tuesday, before the Illinois ruling, Biden said he did not have a problem with Trump being on presidential ballots. Biden made the comment in response to a reporter’s question before flying to Florida for campaign fundraising.

Section 3 was heavily used immediately after the Civil War, but after Congress granted an amnesty to most former Confederates in 1872 it fell into disuse. Legal scholars can only find one example of it being deployed in the 20th century – against a socialist who was not seated in Congress because he objected to US involvement in World War I. It has been used a handful of times since the January 6 attack.

The Illinois board members ducked the issue by concluding that, under state law, all they can do is assess whether the basic paperwork candidates fill out is true. The only way to remove Trump would be by concluding he made a false statement when he swore under oath in that paperwork that he was eligible for the office he sought.

Board member Jack Vrett, a Republican, warned that would create a dangerous precedent, given the dozens of election boards in the state that follow the main one’s lead.

“If we allowed them to say, ‘Don’t just look at the papers, look at the underlying allegations,’ that would open a floodgate,” Vrett said. “Every possible school board candidate would seek to challenge the qualification” of their rival “based on some alleged criminal conduct”.