Standing pensive in the narrow Rua do Bocage alley that pours onto the historic Praça de Ponte e Horta, where aunties exercise and uncles read newspapers and sip tea, I peer up at the 15-storey Hotel S.

Originally built in 1949 as the Hotel Sun Sun (sometimes spelled San San), it is covered in modern street art around the back, with a giant mural of indigo koi fish swimming across the front. Nearly 40 years ago in this spot, Indiana Jones jumped out of a top window.

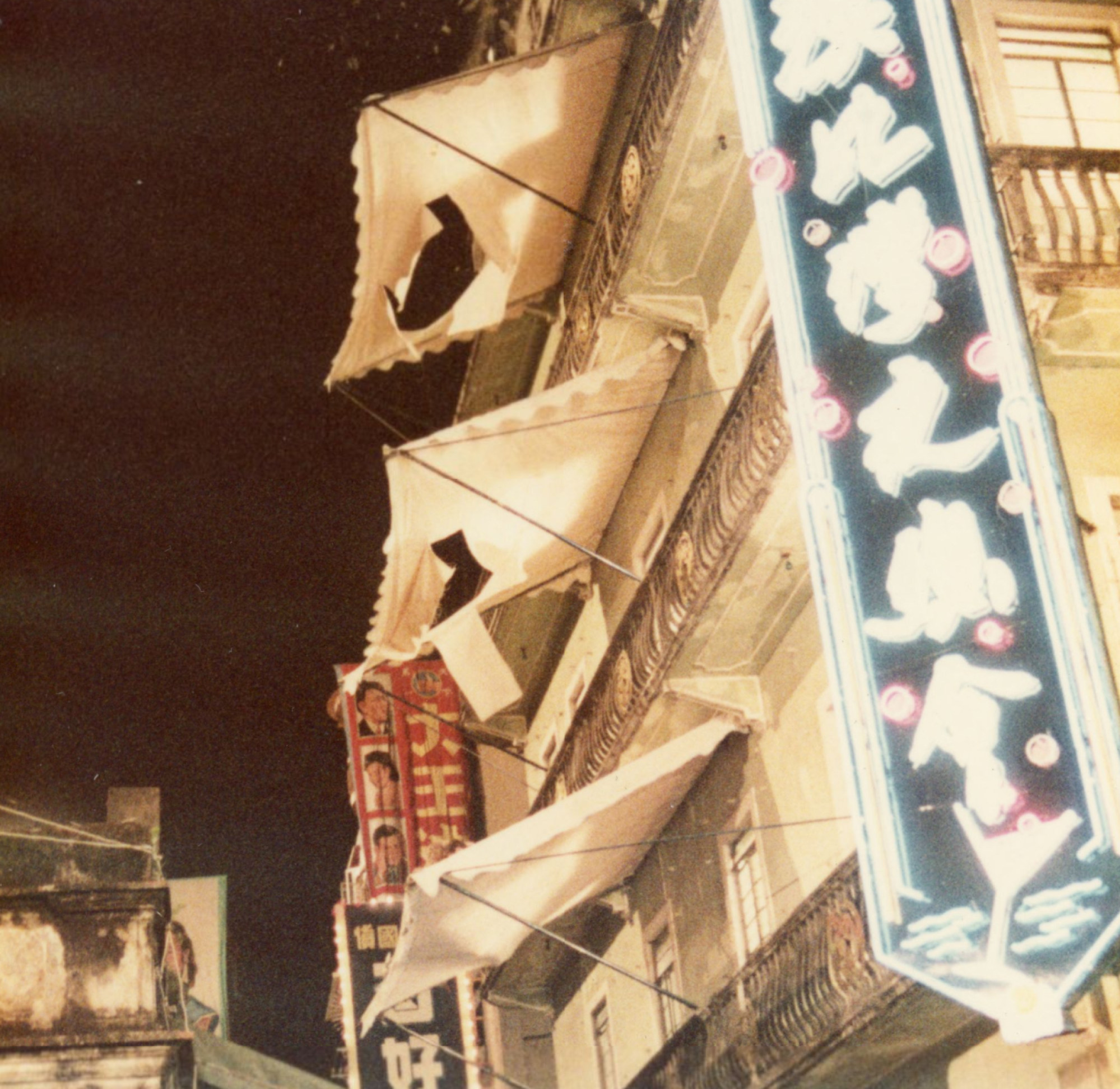

The scene of Indy and heroine hanging onto an awning before they fall into a waiting Cadillac below frames neon Cantonese shop signs looking north into Rua do Bocage.

An alley away from it is the start of a rabbit warren of former bordellos and the red-light quarter of the colonial period that feeds over to the Rua da Felicidade, “the street of happiness” in Portuguese.

After cascading down the side of what was then the Pensão/Hotel Sun Sun, they land in a waiting white 1930s Cadillac manned by a Chinese child named “Short-round”, with wooden blocks tied to his feet so he can reach the pedals.

In the car chase that ensues, locals and Macau regulars will notice small streets and the grand Avenida de Almeida Ribeiro boulevard that slice through downtown are edited rather awkwardly; moving back and forth in second-by-second cuts from alley to main street during shooting.

Today, these old-quarter lanes are inspiring young Macanese artists and filmmakers to breathe new life into these former opium dens, fan-tan gambling halls and bordellos in the decaying Western part of Macau that regularly floods when typhoons strike.

“The old parts of Macau, the real settings of local life, are where many young short-film, independent and anime makers are drawing inspiration to talk about their lives and relationships with their families,” says Rita Wong Yeuk-ying, operational director at Cinematheque Passion, an indie film house supported by the Macau government.

Its relevance speaks to the larger legacy of pre-handover filming, often lost on the Macanese youth of today, with the predominance of Portuguese films and documentaries.

“There are not many chances to screen these movies, or learn about them,” says Wong, “unless you really research.”

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom is an exception to pre-handover 20th century filming here for the West, in that it was not a Macau-casino marketing film.

Hotel S was a stand-in for Shanghai. In fact, says Wong, “it was cheaper to film in Macau [posing] as China in those days over Hong Kong.”

These days, indie productions by young Macau natives are more prevalent than major Hollywood motion pictures.

When I first discovered Hotel S and the folkloric Club Obi Wan, in 2019, the bar was on the ground floor and played Temple of Doom on a big screen, with worn leather chairs to sink into and drink while taking in the spectacle. Film memorabilia and related images lined the walls.

Walking into the lobby today, all mention of the film is gone, the former one-show cinema now a post-Covid, minimalist white cafe.

Upstairs is the austere Epic Food Union restaurant, with a squiggly silver serpent logo, interior of light wood, high ceilings and long tables, and a menu of craft cocktails.

It is peppered not with grim, tuxedoed triads at circular, Chinese-style dinner tables ready to do shady diamond deals, but young artists with forearm tattoos, professionals with designer watches and mixologists with lip rings.

Some servers don a custom shirt with a line Indiana imparted to Short-round after they outran the triads and began their journey in India: “Fortune and glory.”

Most of the time, Macau symbolises an exotic background, but those films don’t represent who Macau really is

Award-winning Macau filmmaker Tracy Choi

Sporting a goatee, Hotel S co-owner Yany Kwan says, “This building was made long ago, in 1949. My father bought it in the early 1980s.

We were here for the filming of the movie. I was young and so happy to see this movie being made. This part of Macau has an old history, so it was good they filmed here.

“When I took over from my father, we renovated several times to keep it modern. During the pandemic I took out the TV playing the movie and we have made it classier, with a few references here and there, more subtle. Younger people now have new tastes in art, music and movies, so we are really attracting them.”

Which is all fair enough, so many decades later, but staying with the film theme, I spy a drink on the menu called the “Temple”, with sandalwood-infused whiskey, ginger and Hinoki bitters, the latter extracted from timber used to make temples in Japan.

The bartender cups the drink and uses a handheld blowtorch to burn a sandalwood ember for the smoke to infuse and flavour the whisky on ice.

![The car in which Indy escapes filmed during production of “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom”. Wong says that at the time, “it was cheaper to film in Macau [posing] as China in those days over Hong Kong.” Photo: Hotel S](https://cdn.i-scmp.com/sites/default/files/d8/images/canvas/2023/11/08/b4373cb9-925e-45d5-8978-068e98c814fd_5b21820d.jpg)

Thankfully, the drink is not laced with poison like in the film, where Indiana’s triad foil Lao Che teased, “Too much to drink, Dr Jones?”

Unlike my smooth sandalwood-smoked whisky, the film has not aged well with more socially conscious young viewers who frequent the hotel these days.

Contemporary audiences can quickly identify old stereotypes, the cartoon versions of Chinese gangsters in the film’s opening scenes.

The same goes for the scenes set in India, where, in a quasi-Hindu ceremony, a cult leader rips out a live beating heart from a sacrificial human chest, and at the end, it is a troop of British Empire sepoys that save the day.

Even when the film was still played on a loop here, mass-market mainland Chinese guests checking in looked on in bewilderment.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Kwan welcomed young artists to use the back alleys for their artwork, and held micro art-installation festivals to help support them.

Twenty-something local cultural promoter Chan Ting Ting, nicknamed Cass, with her blue-streaked shock of dyed blond-silver hair, sits at the hotel’s Epic bar with other artists and mixologists chatting about body art and the 2023 instalment of the Outloud International Street Art Festival she co-organised last month.

“We began back in 2017 in a few local street locations including here,” she says, “but we really rallied around Hotel S during the pandemic years and now opening up. The festival is all about graffiti, street art, hip hop culture, street dance, B-boy and rap, and DJ music.”

“Look here,” says Hotel S and Epic manager Billie Fong as she opens a back door into the alley off the Rua do Bocage.

“The youth are creating their own expressions and paintings now back here. A lot of old movies were made in Macau, from the 1950s to the 1980s, with Indiana as a starting point for reminding them [of that].”

Award-winning Macanese feminist filmmaker Tracy Choi Ian-sin says, “Most of the time, Macau symbolises an exotic background, but those films don’t represent who Macau really is.”

Born in 1988, Choi’s breakout documentary, I’m Here, about lesbians in Macau, won the 2012 Jury Award at the Macau International Film and Video Festival.

Choi has also produced local fictional films such as Sisterhood (2016), Years of Macau (2019) and Lonely Eighteen (2023).

“When I was young, I liked to shoot some short films with my friends,” says Choi. “This was the starting point of enjoying moviemaking.”

Years of Macau, nine stories set between 1999 and 2019, serves as a cinematic microcosm of the first two decades of the city post-handover.

These alleys featured in the film are also attracting international street artists, such as French-Moroccan graffiti artist Ceet Fouad, who came to Macau just for Hotel S and its Indiana Jones legacy.

“I grew up with the Indiana Jones movies,” says Ceet.

“When I saw them in the cinema, it was like a dream, you know. Now, to be able to paint on one of the buildings that was in the movies, I am very proud and honoured to be part of this project, because, for me, art and cinema are always connected.”

Along the Rua da Sé, behind the Macau GPO and Leal Senado Building is Cathedral Cafe, run by Australian Stephen Anderson.

Originally from Brisbane, Anderson moved to Hong Kong 32 years ago and has been in Macau for the past 15.

During his decades in the region, he has been collecting old Macau film posters, many of which adorn Cathedral Cafe’s interior, like a museum exhibition with a Lisbon wine bar and menu built in.

“I have always found the old movies fascinating,” says Anderson. “I picked up the old movie posters [of Macau] in Hong Kong years ago, usually in backstreet wanderings.

“It’s interesting how Macau was very much a centre of the early years of cinema in Asia, particularly the ’30s and ’40s. I believe the 12-plus old cinemas around the city mostly date to those times.”

An anchor piece in Cathedral Cafe is a poster of the 1952 action film noir Macao, starring Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell, produced by Howard Hughes, the famed American engineer, aviator and eccentric.

Anderson says it’s one of his favourite Macau films because it’s “about outsiders and lost souls”.

While Macau’s cinema legacy runs the full gamut of Portuguese art house to Americana noir to two James Bond films to Hong Kong triad action thrillers, hope is riding on a new wave of innovative locals, who, Wong hopes, “will look for their own Macau, in their own movies”.

Or as Dr Jones said to Short-round, “Fortune and glory, kid, fortune and glory.”