“We crossed a river and arrived at a compound guarded by armed men wearing Myanmar military uniforms,” he said.

Upon his arrival at the compound, Awan soon discovered his new “job” was not with Amazon, but rather manning a centre for online scams run mostly by Chinese nationals.

Forced to pose as a successful businessman, he said his role was to cultivate relationships with victims on social media, establishing a rapport before asking for personal details such as their phone numbers and addresses.

“I was told to target individuals with an annual income of more than US$150,000,” he said. “Then a separate team would act on those details by luring the victims into bogus investment, romance or gambling schemes, chosen to suit their profile.”

Working under duress, often for 15 to 18 hours a day, Awan and his fellow captives – Indonesians, Pakistanis, Ghanaians and Moroccans among them – eventually revolted, staging a protest. Their captors promised repatriation, but Awan suspected another ploy and managed to orchestrate an escape with a fellow Indonesian from Sumedang while they were supposedly being transferred to Chiang Mai in November.

“We suspected we were just being moved to another facility, so we escaped on the way when we had the chance,” he said.

Borrowing a taxi driver’s phone, Awan managed to reach out to the Indonesian embassy in Bangkok, which referred him to Ezekiel Rain, a US anti-trafficking NGO with operations in Thailand.

The NGO took both Indonesian captives into its shelter for two weeks as they filed reports with the Thai police. Yet Awan was dismayed by the absence of any Indonesian embassy or consular staff to support them through the legal process.

When Awan finally made it back home late last year, he dutifully filed another report with the police in Jakarta, naming his local recruiter as part of the criminal syndicate.

“But so far I haven’t heard back about my case,” he said, lamenting the lack of interest from Indonesian authorities.

Liberating loved ones

A free man once more, Awan remains determined to help other Indonesians still trapped overseas by the criminal syndicates.

In March, he co-founded Jerat Kerja Paksa (Forced Labour Entrapment) – a solidarity group comprising survivors and families of victims. Its mission is to offer emotional and practical support for Indonesians working to liberate their loved ones.

Bandung-based Yulia Rosiana is an avid campaigner with Jerat Kerja Paksa. Her older brother remains trapped somewhere in Myanmar by the trafficking syndicates.

“My brother left the country in November 2022 for Thailand, and we didn’t hear from him for months before receiving a short furtive message saying he was in Myanmar working under guard,” she said.

Fearing retaliation, Yulia asked This Week In Asia to keep her brother’s identity secret, as her family had received threats and ransom demands of US$10,000 from the syndicates.

There’s a tendency in Indonesia to blame the victims

“There’s a tendency in Indonesia to blame the victims in cases like my brother’s. People would ask why the victims and their families came to trust the recruiters in the first place,” she said, noting that her brother’s placement had been arranged through a legal, Labour Ministry-certified agency.

“I’ve filed reports with the police, human rights commission and lobbied the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but things are moving at a slow pace, with no light at the end of the tunnel remotely in sight.”

“There is no one-size-fits-all solution to this problem because each country requires a different approach,” he said. “Myanmar, for one, is a conflict zone, which makes our efforts even more challenging.”

However, Yulia argued the government should recognise the “invisible victims” of human trafficking – the left-behind spouses and children.

“What about the family members of those being kept under lock and key and forced to work overseas? Most left behind spouses and children,” she said.

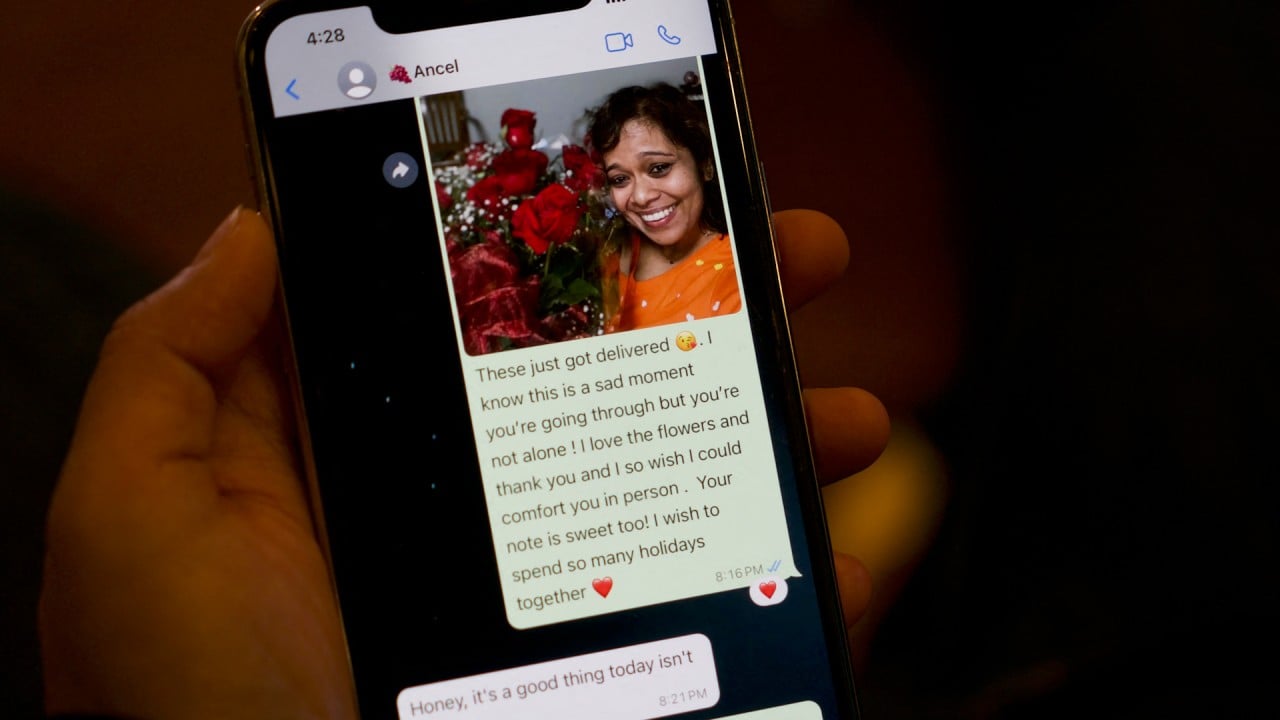

Through Jerat Kerja Paksa, Yulia said she has met women whose husbands remained trapped abroad now struggling to support themselves and their children.

Integritas Justitia Madani Indonesia, an NGO that advocates for trafficking and slavery victims, says more cases of Indonesians being illegally recruited by crime syndicates are emerging.

“While the government has no definite numbers, we estimate there are thousands of families with family members enslaved by the syndicates,” spokesman Harold Aron said.

His organisation is helping coordinate victims’ and families’ efforts to seek justice, as well as asking Indonesian law enforcement to “map out and root out” local recruiter networks and work with neighbouring countries to combat the syndicates, he said.

The NGO and Legal Aid Surabaya filed a new case on Thursday with the police in East Java on behalf of a 22-year-old from Blitar who escaped a work camp in Cambodia.

Habibus Solihin, a lawyer with the legal aid group, told This Week in Asia that the latest cases revealed a new recruitment pattern among the traffickers.

“No longer content in using work agencies, they now employ individual agents who recruit their victims by word of mouth and personal overtures on social media,” he said, urging Indonesian police to intensify their efforts and vigilance against the growing phenomenon.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime set up a regional emergency response network in May to fight human trafficking for forced criminal activities, especially scam operations.

“Southeast Asia has faced unprecedented challenges from powerful transnational criminal groups involved in money laundering, cybercrimes, kidnapping, extortion, and torture,” said Rebecca Miller, UNODC’s Southeast Asia and Pacific regional coordinator for countering human trafficking and migrant smuggling, at the time.