Human Rights Watch said in a 2023 report that it had collected information on 37 political prisoners in Bhutan detained between 1990 and 2010 – the number could be much higher. Of those, 24 were serving life sentences while others were jailed between 15 and 43 years.

The Bhutanese authorities should “urgently remedy the situation,” she added.

A dark past

Ram Karki was part of a primary teacher training programme in Bhutan in 1990 during the initial human rights demonstrations by thousands of ethnic Nepalis in southern Bhutan, where most of the Lhotshampas lived.

“Those who were in the streets were identified and given 24 hours to leave the country,” said Karki.

In the 30 years since Bhutan’s ethnic cleansing of its Nepal-speaking population, the country had introduced political reforms including its transformation into a constitutional monarchy and holding its first National Assembly elections in 2008. With a liberal leadership heading a new government in January, activists and families of political prisoners hope it would initiate steps to free the inmates.

Susan Banki, an associate professor at the University of Sydney, told This Week in Asia that Bhutan still portrays its political prisoners as criminals and the government’s refusal to release them shows it is unwilling to drop that narrative.

“This is not a great look for democracy because it suggests that people should continue to fear expressing themselves,” said Banki. “But the issue of the release of political prisoners is straightforward because their release … would be a public relations ‘win’ for the government.”

Is India’s billion-dollar aid to Bhutan aimed at curbing China’s influence?

Is India’s billion-dollar aid to Bhutan aimed at curbing China’s influence?

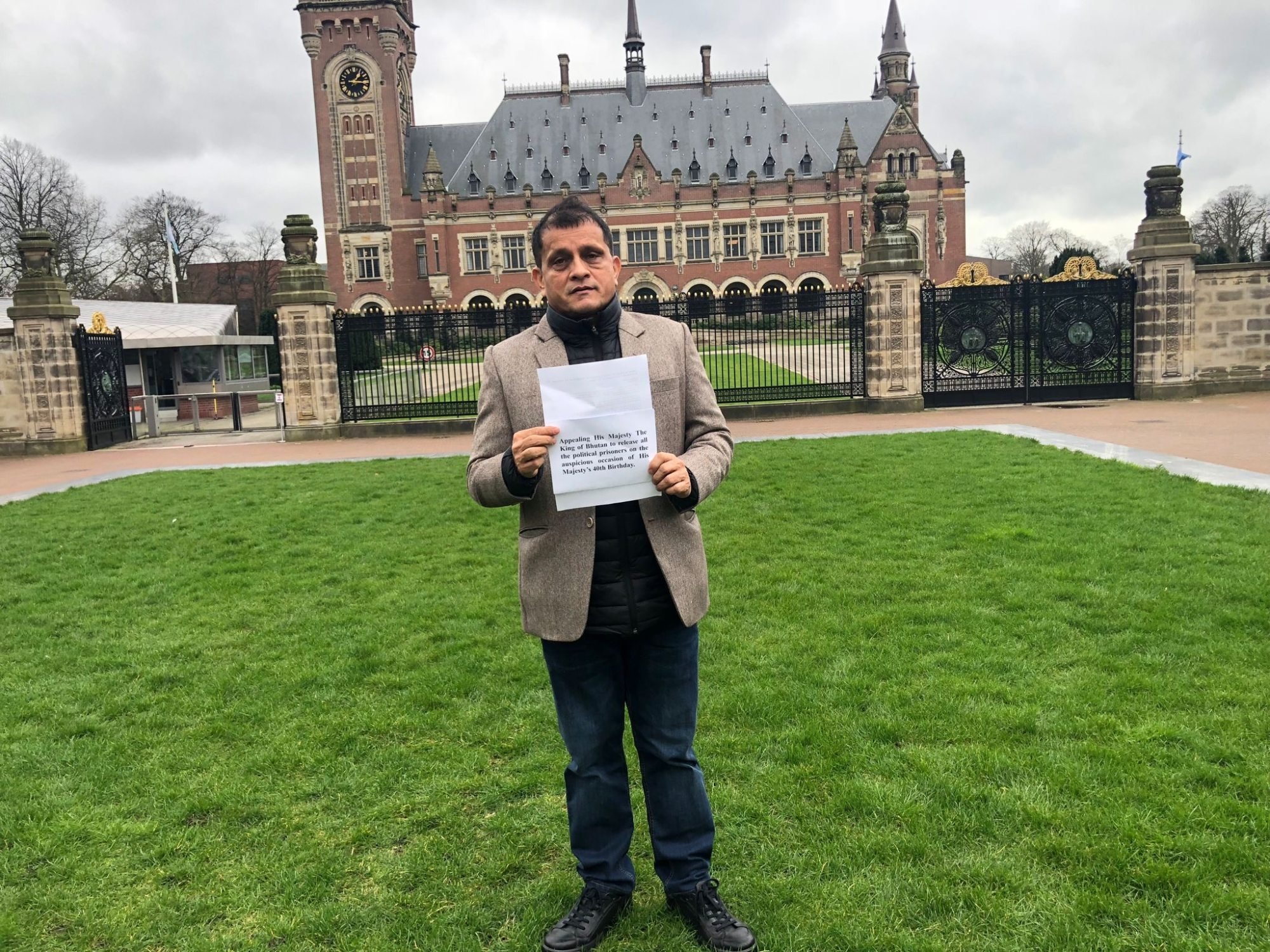

Campaigning for release

In July 2019, Karki said he received a handwritten letter from a political prisoner in Bhutan through a third person via Facebook. It said those who have resettled in other countries may have “forgotten our plight” and asked Karki to take up the issue.

Karki and Human Rights Watch were able to find details of 37 of them, two of whom have been released since the HRW report was published. About 15 of the 37 were convicted in the 1990s for protesting against the Nepali community’s mistreatment, while others were either jailed while revisiting family members they left behind or those helping the returnees.

Many of them are said to be in Chemgang Central Prison, near the capital Thimphu, while others are in Rabuna and Paro prisons.

Rai, who was jailed in Chemgang and freed in 2017, said conditions in the prison were poor – inmates were not given proper food or medical care and had to use buckets to relieve themselves.

Rai said he was also tortured during custody, with police officers stamping on his chest and hands, as well as depriving him of sleep.

“I was in jail when democracy came to Bhutan but it didn’t make any difference to the political prisoners,” he said.

After visiting Bhutan in 2019, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention noted that several prisoners had been imprisoned under national security legislation, with a number of them serving life terms. The report said the working group was “informed of a number of due process violations” and those serving life sentences had no prospects of release except for amnesty.

“Bhutan government doesn’t have to fear us,” Karki said. “The political prisoners aren’t harmful. The government should release them on humanitarian grounds.”

Bhutan’s Ministry of Home Affairs did not respond to emails seeking comments from This Week in Asia.

In limbo

Shantiram Acharya was released from Bhutan’s prison in 2014 on humanitarian grounds, some seven years after he was arrested while attempting to visit his homeland. He said the torture he endured while incarcerated had left him paralysed below his waist.

“I was all alone when I came to Nepal from jail, and I was sick” he told This Week in Asia, adding he hopes to once again meet his almost 80-year-old mother.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) started arranging family visits after receiving the greenlight from the Bhutanese authorities in 2004, said Sandesh Shrestha, the organisation’s head of mission in Nepal. During those visits, it also assessed the conditions of the jails. The visits were stopped in 2012, with Bhutan saying it had taken measures to improve prison conditions as per ICRC recommendations and standards.

Dhan Bahadur Basnet said his brother, Nanda Lal Basnet, had gone to Bhutan to find their missing sibling Kul Bahadur Basnet in 2008. Nanda Lal was arrested and is now serving a life sentence in Chemgang for “treason”.

“We haven’t been able to contact him or call him since 2014,” Dhan Bahadur, who now lives in the US along with his family, told This Week in Asia. “If we can’t even make a phone call, it’s hard to hope for his release.”

Rights activists have repeatedly urged the Bhutanese government to make such arrangements.

YouTube series aims to change face of Nepali journalism through human stories

YouTube series aims to change face of Nepali journalism through human stories

“There hasn’t been much progress on the release of the political prisoners since 2023,” Deekshya Illangasinghe, executive director of South Asians for Human Rights, told This Week in Asia, referring to the Human Rights Watch report.

“The government of Bhutan has not had a public position on this issue or acknowledged its political prisoners,” Illangasinghe said.

At the refugee camp in Nepal, Rai said life for many of the remaining refugees remains in limbo. He said freedom from prison was like “starting life again” but his daily routine since has become stagnant, with little hope of a better future.

“We don’t want to be lifelong refugees,” he said. “I was in my 20s when I left Bhutan, so I have vivid memories of my country. If the government decides to take us back, I will return immediately.”