It has filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court seeking the annulment of the Citizenship Amendment Rules, 2024, while asserting that the Centre’s notification of the Rules on 11 March contradicts the Assam Accord and Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955. The AASU believes that the CAA contradicts the purpose of the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

Earlier this month, Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma asserted that he will step down if non-NRC applicants gain citizenship via the CAA — his words seems to have calmed tempers and slackened the movement, but analysts and political observers also point at the dwindling clout of the organisation, whose six-year movement against ‘outsiders’ or ‘foreigners’ had led to the Assam Accord in 1985.

Six decades since its inception, critics point out the past lapses and the present AASU leadership’s test of sincerity over the CAA issue. A sequence of interrelated events over the past almost two decades has gradually dragged the students’ organisation into virtual insignificance, they say.

The weakened movement has led to some analysts questioning if many sympathisers of the cause are also suspicious of the AASU’s sincerity because of its “past history of alleged compromise”.

While the election fervour has taken much wind out of the AASU’s sail, some feel that the only recourse is now through the doors of the Supreme Court — the apex court has already taken up the issue for examination.

“The AASU has failed to calibrate its strategies with the changed political environment. It is not surprising that the organisation finds itself in a mess now, and is unable to retain the space in student politics,” one of the observers tells ThePrint.

But, AASU advisor Samujjal Bhattacharyya tells ThePrint that the focus remains intact since its formation — securing the future of Assam and the indigenous people, and a safe future for the students.

“It is a continuous journey, a continuous struggle. Whenever there has been a crisis situation affecting the indigenous people, the AASU has led from the front. Since the very beginning, we have covered many milestones, and as time changes, and with advancement of technology, our strategies too have changed,” Bhattacharyya says.

Another political analyst claims that the movements of the AASU have lost steam over the years even as the students’ union along with the Asam Sahitya Sabha, the apex literary body in the state, remain the “pillars of the Assamese community”, the Jatiya (national) organisations.

“Along with the AASU, Assam has seen the emergence of several ethnic organisations led by youths in their districts. That the AASU needs the support of 30 ethnic groups suggests it has weakened over the years. The way it collectively led movements in the past involving the entire student fraternity of Assam is not much seen now. It also indicates the eroding support of people in different parts of the state towards the student body,” the analyst said.

“Even during the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) rule, the way the AASU was expected to fight for the rights and identity of the Assamese people did not happen. Today, the CAA has been implemented in Assam. Will the AASU still restrict itself to memorandums and slogans?”

The AGP leaders were primarily student activists of the Assam Movement. Formed two months after the Assam Accord was signed on 15 August 1985, the AGP had gone on to win the state election held in December that year under the leadership of Prafulla Kumar Mahanta. The AGP formed the government for a second time in 1996.

Similarly, former chief minister Sarbananda Sonowal, who moved the Supreme Court against the now scrapped Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act, began as a student leader with the AASU before joining the AGP. In February 2011, he resigned from the AGP and joined the BJP which made him the chief minister five years later.

Bhattacharyya clarifies that the AASU will work only with ideologically similar outfits and on common grounds.

“When violence erupted in Barpeta during the NRC updating exercise in 2017, AASU and 26 ethnic organisations joined hands against the Bangladeshi lobby. The number gradually increased to 30. We are working together on common issues, and also with the Sahitya Sabha units. It’s a cordial atmosphere in Assam because of that,” he says.

Former Assam DGP and noted writer Harekrishna Deka feels that the AASU-led agitation in 2019 received mass support, mostly in urban centres, but the message failed to reach the rural areas.

“The existential fear of the indigenous people is strong but at the same time, no ethnic organisation has been able to earn uncritical trust of the people. They are unable to galvanise rural people as before. The Assam Agitation, having begun with a roar, ended in a whimper; the people resignedly, but grudgingly accepted the Assam Accord. The masses seem not so much influenced by the exhausted pattern of agitation and do not give blind support to these methods as they did before,” he says.

Sounding a caution, Deka says a possible reduction of ethnic population can prove disruptive in the future, as is being witnessed in Manipur. The discontent may have apparently weakened on the political surface — with strong undercurrents not visible on the ground, he warns.

“If the next Census shows that the percentage of ethnic population has been reduced, resulting in further erosion of their political space, a centrifugal force may manifest strongly to complicate the federal structure. Though the issues of Manipur and Assam are different, its fault line may equally be complicated.”

Reacting to the announcement of a statewide anti-CAA agitation, Raijor Dal chief and Sivsagar legislator Akhil Gogoi had said that AASU’s movement was nothing but a “drama to show its presence”.

“CAA is unconstitutional, communal and a legislation against the interests of the Assamese community. Assam’s 80 percent population had revolted against the CAA in 2019. But AASU’s programme suggests only that they have taken up certain plans in consultation with the state government, possibly not to upset it,” he tells ThePrint.

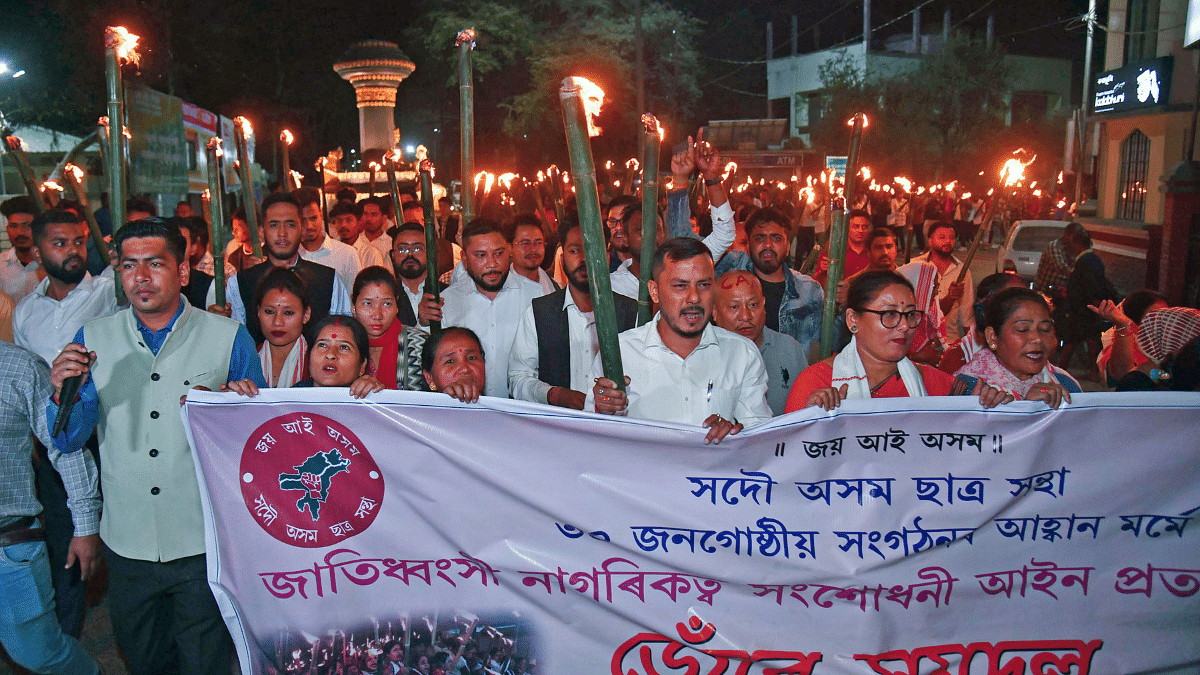

Also Read: Renewed protests in Assam over CAA rules notification

Student politics in Assam & AASU’s journey

As seen in the role played by All India Students Federation‘s (AISF) Assam unit during the freedom struggle of India, students were at the forefront of socio-political movements post Independence too — be it the Refinery Movement of 1956, and the Language Movement in the 1960s.

In the decade that followed, an upsurge in student activism was seen in the 1972 movement that demanded Assamese as a medium of instruction up to university level, the 1974 Food and Economic Agitation, and the 1979-85 Assam Movement that sought the detection of illegal immigrants, their deletion from voter list and deportation to Bangladesh.

Formed in 1967, the AASU was a result of the churn generated by political parties and organisations who came together, despite political and ideological differences, to wage a joint struggle against the then prevailing economic crisis including price hike of essentials.

Slowly, AASU gained significance as a mass students’ base, and assumed an independent and apolitical character. The next 15-20 years following the sixties were the decades of protest and political turbulence in Assam. While the aspirations of many of these student leaders remained unfulfilled, some were driven to consolidation of power by joining politics.

The analyst quoted earlier believes the year 1985 was the end of AASU’s character as a formidable student organisation, especially after the formation of the AGP.

“AGP and AASU worked in a parallel way — each influencing the other in different times. After 1985, their movements haven’t been able to make progress. The mindset of youth changed, too. They started to believe that the platform of AASU is their next step to politics,” he says.

Elaborating on the role of the AASU leaders who joined politics, Deka terms it a “poor shadow of its predecessors”.

“After the Assam Accord, the student leaders’ hidden agenda of capturing political power was exposed, and misgovernance made them unpopular. The next generation of the AASU still gained some emotive space on various issues, but it has never been overwhelming. There has been loss of credibility of AASU leaders over the years,” the writer said.

Also Read: Will resign if anyone not part of NRC gets citizenship, says Himanta amid CAA protest in Assam

‘No results for Assam Accord, NRC & CAA’

According to the analysts, the AASU has failed to see any cause to its logical conclusion — be it the NRC, the CAA, the Clause 6 of Assam Accord, the recent threat to Assamese language as medium of instruction, or the standard of higher education in Assam.

As an example, one of the political analysts highlights the delay in implementation of the Accord that was signed between the Centre and the leaders of the AASU and the regional political party, All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP).

The Assam Accord promised that all immigrants who arrived in Assam after 1965 would be disenfranchised, and deportation of those settling after 1971. Also, the date of 25 March 1971 was accepted as the cut-off date for the identification of “foreigners”. This officially marked the end of the six-year Assam Movement that started in 1979.

But Assam “could not recover from the deep scars left by the political unrest”, writes Professor Arupjyoti Saikia in his book ‘The Quest for Modern Assam’.

The promises made in 1985 still remain unfulfilled, asserts a senior citizen of Guwahati. “After six years of the Assam Movement, and almost 40 years since the Assam Accord was signed, nearly 46 years have gone by — and we have only raised slogans, bearing no results.”

On his part, Bhattacharya says that non-implementation of the Assam Accord is a government problem.

“AASU has been continuously hammering for implementation of the Assam Accord and all its clauses. All consecutive governments did nothing to take it forward. It is only because of the AASU pressure to implement Clause 6 that the government formed a high-level committee. AASU members were also part of the committee, and we could submit the report in time. But till date, it has not been implemented,” he says.

The clause deals with legislative and administrative safeguards promised by the Centre to protect the Assamese cultural, social and linguistic identity, and heritage.

“We want the foreigners’ issue to be solved urgently. The final NRC results were not satisfactory when we found that over 40 lakh people were excluded. These numbers are given by the government, not the AASU. We demanded recertification long back for a Bangladeshi-free NRC,” Bhattacharyya says.

In leading the anti-CAA movement, Bhattacharya says that the people of Assam wanted a democratic, peaceful and non-violent movement.

Justifying the organisation’s role in the anti-CAA movement, he says that the AASU was the first from Northeast to file a petition challenging the act. Of the 247 petitions from across the country, 53 are from the Northeast including 50 from Assam, Bhattacharyya tells ThePrint.

Deka asserts the Centre tackled the CAA issue “cleverly” by not framing rules, and could divert the attention of the masses from it after the declaration of elections.

“The leaders of AASU and other organisations formed different political parties, thus diffusing their strength. The message against the CAA did not percolate down to the rural masses, and politically, these leaders cut a sorry figure in election,” he added, referring to regional political parties formed after the unrest like the Asom Jatiyatabadi Parishad (AJP) led by former AASU general secretary Lurinjyoti Gogoi, and the Raijor Dal.

The AJP and Raijor Dal, formed by a committee of Assamese intellectuals constituted by the AASU and the Asom Jatiyatabadi Yuba Chatra Parishad (AJYCP), had jointly decided to contest the state election in 2021. Lurinjyoti Gogoi rose to prominence in 2021 after the formation of the AJP.

There have also been numerous incidents of AASU leaders shifting allegiance from one political party to another.

For instance, AASU leader Zoii Nath Sarmah served as MLA from 1991 to 2001 in Sipajhar constituency on AGP ticket, and later joined the Congress in 2016. In January, AASU president Dipanka Nath, who severed his 20-plus years ties in 2022, joined the BJP. He was joined by former AASU vice-president Prakash Das. The next month, Congress leader Shankar Prasad Rai, who was formerly with the students’ outfit, joined the BJP.

The analyst explains that if AASU has to return to the glory of its formative years, it has to fulfil all causes taken up till date — in a time-bound manner, “by staying apolitical, and with people’s support”.

“The AASU had been a powerful organisation. If the AASU has grown weak, it means a big loss for Assam. For the future of the student fraternity, the AASU should introspect and revise its strategies. With the formation of every new committee, the previous committee of the AASU leadership leaves the organisation to join politics,” he says.

Bhattacharyya, meanwhile, asserts that the organisation still remains “apolitical”.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: ‘Even Ram bhakts in Assam don’t have Aadhaar’: Congress MLA & CM Sarma’s war of words over NRC