“The key moment in Barbie is when she goes from perfect beauty to bad breath, cellulite, and flat feet. Or what casting directors call a character actor,” he continued, to groans from the celebrity audience.

The assessments of his performance were brutal, with reviewers describing it as a “catastrophe” and “profoundly uncomfortable”. But some of the harshest comments came from the Philippines.

“My grandma survived WWII and she’s never seen a Filipino bomb this hard,” one X user said in a post that received more than 8,000 likes.

Another said Jo Koy brought her “deep Filipino shame”, while one user went further and proclaimed the comedian to be an “embarrassment to all Filipinos”.

While they were in the minority, there were a few people who publicly defended Koy.

“[Jo Koy’s] got balls made of iron to accept that hosting responsibility. That alone deserves a round of applause,” said a popular content creator said in a Facebook post, earning over 132,000 likes.

“Accepting the task in the very first place displays [Jo Koy’s] Filipino courage,” said another influencer on Facebook.

Seeking validation

“Pinoy” is a colloquial term to refer to Filipinos, and “Pinoy pride” occurs when someone of Filipino descent is recognised on the international stage or even when a foreign personality or film makes a passing reference to the Philippines.

Kim Bernard Fajardo, assistant professor at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines’ Department of Broadcast Communication, describes the phenomenon as complex and diverse, “characterised by a sense of shared identity based on cultural pride, patriotism and a desire for positive depiction”.

“Their accomplishments serve as a source of inspiration, instilling a sense of belonging and pride that promotes the belief that Filipinos can make a difference on a worldwide scale,” he said.

Champion boxer Manny Pacquiao and Miss Universe 2018 Catriona Gray are among the figures treated as national heroes.

The inverse of that explains why Koy’s performance seemed to sting so many Filipinos. When one falters on the global stage – not the least in a room of Hollywood’s elite – it can be viewed as a collective failure.

Fajardo says the successes of individuals like Koy become a reflection of their own potential, allowing them to defy stereotypes and empower their self-perception.

“The collective sense of ownership over their success transforms into disappointment and criticism when these representatives deviate from the expected standards,” he added.

Fajardo believes this cultural behaviour is a legacy of the Philippines’ colonial past.

Spain colonised the Philippines for more than 300 years and the United States’ occupation lasted nearly 50 years. Natives were labelled as indios, the lowest rung of the societal ladder, while Americans called Filipinos their “little brown brothers”.

Yet decades after gaining independence, Filipinos continue to measure their worth against Western ideals and standards, Fajardo says.

“The praise and backlash surrounding Pinoys on the global stage are influenced by a complex interplay of cultural identity, nationalism, and the deeply ingrained need for external approval,” he said.

“The phenomenon is a double-edged sword, as it reflects both a yearning for international recognition and a potential internal struggle to assert a distinct Filipino identity free from external validation.”

Athena Charanne Presto, a sociologist at the University of the Philippines, argues that Pinoy pride goes beyond international recognition to asserting a national identity distinct from its colonial underpinnings.

The desire for a distinct cultural identity is especially strong among the Filipino diaspora, such as in the US – home to the largest concentration of overseas Filipinos – where such representation can be limited.

This becomes more potent when one considers the experiences of overseas Filipino workers, who leave their families behind and endure hardships in search of better opportunities.

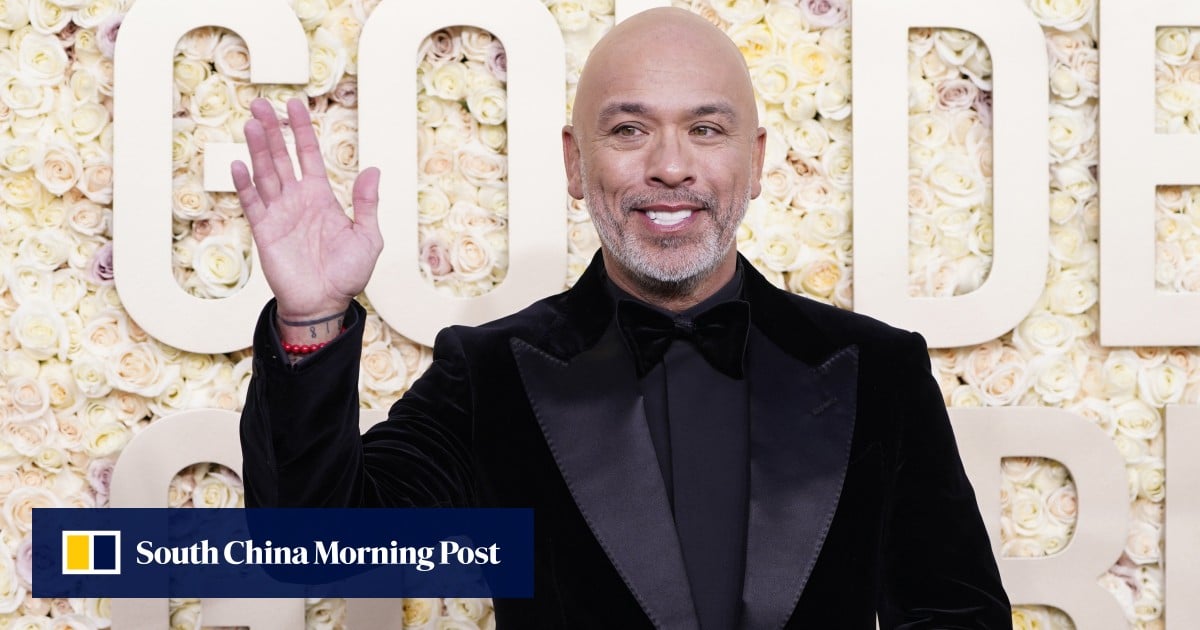

Jo Koy, son of a Filipino immigrant, fits the bill for a figure of national acclaim after achieving considerable international success. Yet it also means bearing the weight of the flag and expectations of an entire people.

“Jo Koy’s success comes from the fact that Filipinos want representation, especially because of our colonial history. For the longest time, some Filipinos have been finding it hard to think about a distinct cultural trait that we can call our own,” Presto said. “So any affront to Jo Koy is seen as an affront to one’s identity.”

Stand-up solidarity

Comedians from the Philippines’ stand-up scene say the odds were stacked against Koy from the start.

“I honestly felt bad for Jo Koy. He’s obviously a talented stand-up comedian, has paid his dues and has worked hard to becoming one of the biggest comedians in the industry,” said Edward Chico, a Manila-based lawyer and a stand-up comedian.

Kel Fabie, a comedy magician and host, said Koy was out of his depth at the Golden Globes. “Were some of his jokes inappropriate? Sure, but that never stopped people like Ricky Gervais before.”

Both Chico and Fabie agreed there were several factors behind Koy’s poor performance, such as him being given the job just 10 days before the event, its deviation from his usual brand of comedy, and lacking the A-lister status of previous hosts like Gervais that protected them when delivering roasts.

Despite this, Chico and Fabie said Koy’s popularity had opened doors for the Philippines’ once-languishing stand-up comedy scene.

“To a certain extent, he was responsible for mainstreaming point-of-view comedy, as Filipinos prefer insult-based and slapstick comedy. Because of Jo Koy, it is now easy for stand-up comedians like me to find an audience. He paved the way and I am thankful to him for that,” Chico said.

“He brings attention to the alternative type of comedy that isn’t as mainstream [locally],” Fabie said.

Has the Filipino diaspora fuelled Jollibee’s global growth?

Has the Filipino diaspora fuelled Jollibee’s global growth?

Koy is subjected to such high levels of scrutiny as a Pinoy pride poster child, which Chico believed stems from a misplaced yearning to elevate the country’s middling reputation.

“We seek validation from the rest of the world because we want to secure our national identity and sense of pride as a people … Jo Koy embodies that sense of pride. And as we live vicariously through him, we celebrate with him when he succeeds but also get hurt when he fails,” Chico said.

One takeaway from the debates over Koy’s performance is that Pinoy pride merits a nuanced take, so the weight of a nation’s diverse yet collective identity does not rest on any one man’s shoulders.

Another may be to simply accept the good with the bad. As Fabie put it: “Yes, we can be proud that Jo Koy is representing us at the Golden Globes, but it’s also fair to say he didn’t exactly do an excellent job at it.”