Hongkongers in their prime were the largest proportion of 184,700 people who left for Britain under a bespoke migration pathway since 2021, leaving a population expert with concerns that the city has lost talent that will be hard to fully replace.

They took their school-going children with them, and many also had babies after settling in the United Kingdom, adding to the overall loss to Hong Kong.

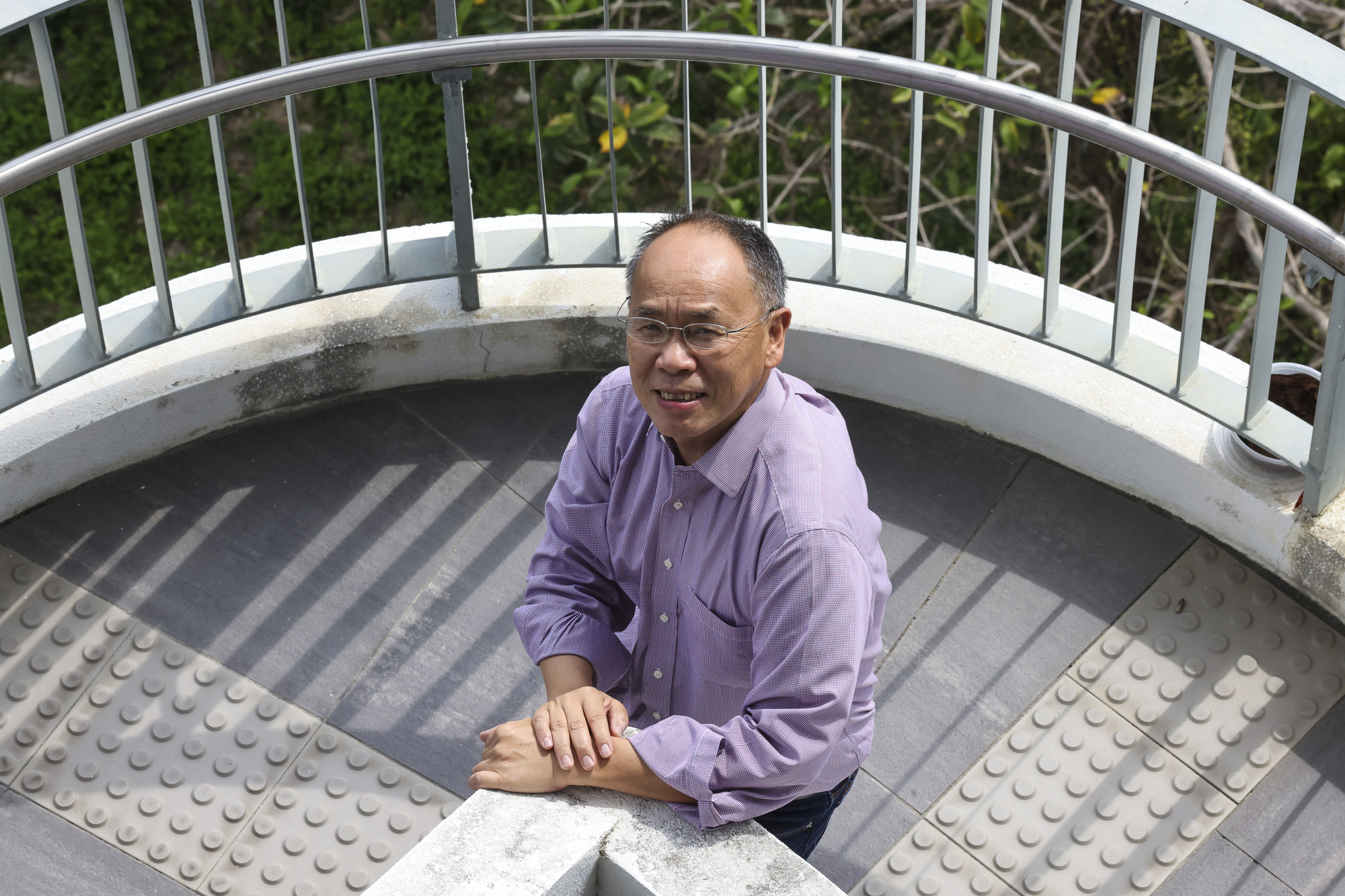

“The middle-aged in their 30s and 40s, who took their kids, wealth and knowledge to the UK, still have 20 years or even more to contribute to the workforce. They are the backbone of a city’s development,” said Paul Yip Siu-fai, chair professor of population health at the University of Hong Kong.

About 44,000 Hongkongers in their 40s, born in the 1970s and early 1980s, made up the biggest group and accounted for one in four who left. Next were more than 30,000 people in their 30s.

About 48,600 children and teenagers below 18 left the city. They comprised about 13,000 between zero and five years old, 22,700 aged six to 11, and 13,000 aged 12 to 17. Almost 20,000 others in their 20s also left.

It allows Hongkongers to live, study and work in Britain for five years, after which they become eligible to apply for permanent residency and citizenship.

Population scholar Yip said the data revealed several areas of concern for Hong Kong, aside from losing people in the prime of their working lives.

He said those in their 30s were in the fertile age range, and Hong Kong had lost their babies at a time when the number of births in the city had sunk sharply.

The number of babies born in Hong Kong fell to 32,500 in 2022, the lowest number since data has been available, and rose slightly last year to 33,200.

Yip said the impact of migration on Hong Kong schools was also plain to see, as the school-going children who left were equal to axing about 40 primary and 20 secondary schools in the city.

Among the older Hongkongers who moved to Britain were more than 23,000 in their 50s, over 10,000 in their 60s and over 4,400 aged 70 and above.

Hong Kong has announced various talent schemes to attract newcomers to fill the void left by those who emigrated and most of the arrivals so far have been mainland Chinese.

UK’s plan to curb ‘far too high’ arrivals ‘may hurt Hong Kong BN(O) migrants’

UK’s plan to curb ‘far too high’ arrivals ‘may hurt Hong Kong BN(O) migrants’

Yip doubted if the influx of mainlanders could make up fully for those who left, as the latter were from a diverse range of occupations whereas the arrivals tended to be mainly in sectors such as information technology and finance.

“We lost talent in culture and the arts too, but will people from elsewhere come to Hong Kong when there are different restrictions in that sector?” he asked.

Sid Sibal, search firm Hudson’s vice-president of Greater China and head of Hong Kong, said people in their 30s and 40s were the mid- to senior-level demographic of the city’s working population.

He said the soft job market in Hong Kong last year and this year meant weak demand for additional talent.

Although there were still shortages in white-collar sectors such as technology, new entrants were helping to make up for those who had left.

Half of BN(O) migrants jobless, but 99% do not plan to return to Hong Kong: poll

Half of BN(O) migrants jobless, but 99% do not plan to return to Hong Kong: poll

Chu Kwok-keung, a lawmaker representing the education sector and a primary school principal, said the sector had been pouring human resources and money into attracting students, as it suffered the double whammy of the emigration wave and the low number of births.

“Making a video and printing a promotional booklet to introduce the school cost around HK$20,000 to HK$30,000 [US$2,500 to US$3,800]. If all these resources went towards teaching and learning, it would be much more worthwhile,” he said.

He said the loss of more than 48,600 youngsters not only dealt a blow to the school sector but also future human resources for the job market.

“They were all originally the future of talent in Hong Kong and the productive power of the society, but they have now all gone,” he said.