“Amitabha!”, Hung shouted in character, before climbing up three tables stacked on top of each other and then somersaulting back to the ground. He hurt his leg, was in great pain, but Yu ignored his pleas and Hung finished the show limping.

“In the two months that followed,” Hung, now 72, recalls, “I wasn’t able to train at all. I was just sitting around and eating. I happened to be going through my adolescent growth spurt and my weight ballooned as a result.”

It is certainly rare for a martial arts actor as venerated as Hung to be his size, especially back in his prime.

“I didn’t mean to keep my body shape like this, I just let it develop as it pleased,” he chuckles. “I’ve maintained my body shape ever since because my intestines are well developed and they absorb nutrients really well.”

The 25 best Asian martial arts movies of the 21st century ranked

The 25 best Asian martial arts movies of the 21st century ranked

Incidentally, the luxury hotel is a few minutes’ walk from Mirador Mansion, the building in which Hung had been undergoing his gruelling training with Yu around the time of his injury.

These days, Hung looks a bit slimmer than the portly figure to which audiences have long grown accustomed.

This has primarily to do with the diet orchestrated by his wife, the former Miss Hong Kong and actress Joyce Godenzi, who is 58. She is sitting across the room from us with great poise, supplying Hung with snippets of information – usually film titles – whenever memory fails him.

In Hung’s case, those gaps in recollection are probably less a consequence of “dementia” – as he has somehow seen fit to joke about on occasion – than the fact that he has worked in a staggering number of films.

“I don’t know why,” he offers at one point, “but since I started working as a filmmaker, all the way up to this moment, I’ve always felt like I know nothing about anything.

“Even in the old days, I had no idea at all about the salaries that my actors were getting,” says Hung. “I just told my producers that I wanted this or that actor, and then they would sort it out for me.

“For me to be able to make so many films in this industry, it’s all about the many kind and capable people who have been helping me out. Even now, I’m still very much like a kindergarten kid.”

Shaolin Plot might be ‘the best martial arts movie you don’t know’

Shaolin Plot might be ‘the best martial arts movie you don’t know’

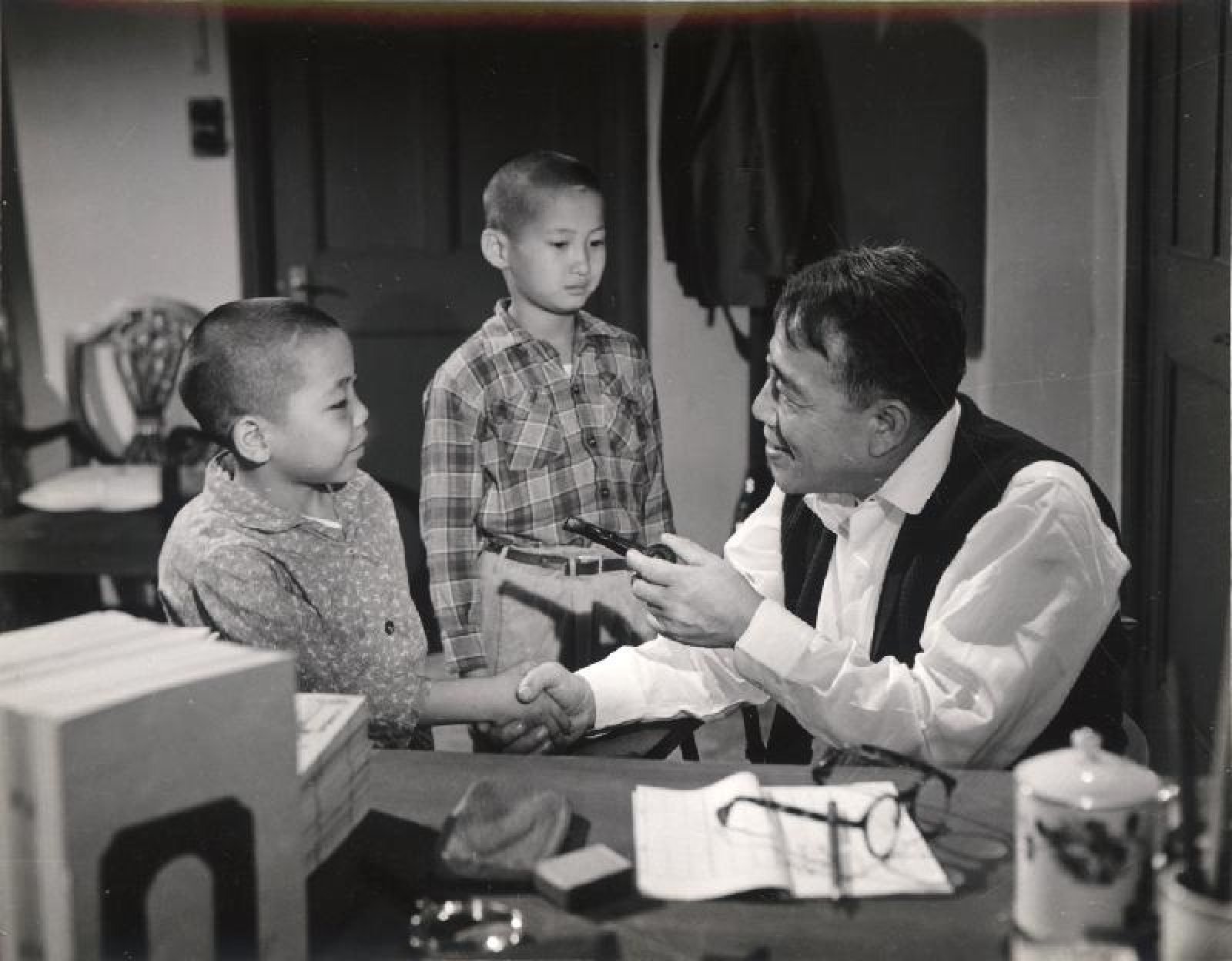

Sammo Hung was born on January 7, 1952, in Hong Kong, into a family tree weighted with film industry workers. When he was little, his mother would call him “Sanmao” – “a common way Shanghai people called their kids”, explains Hung.

The change of scenery seemed like a good fit for the boy: he was struggling to complete his Primary 2 school year for the third time, while frequently getting into trouble on the streets.

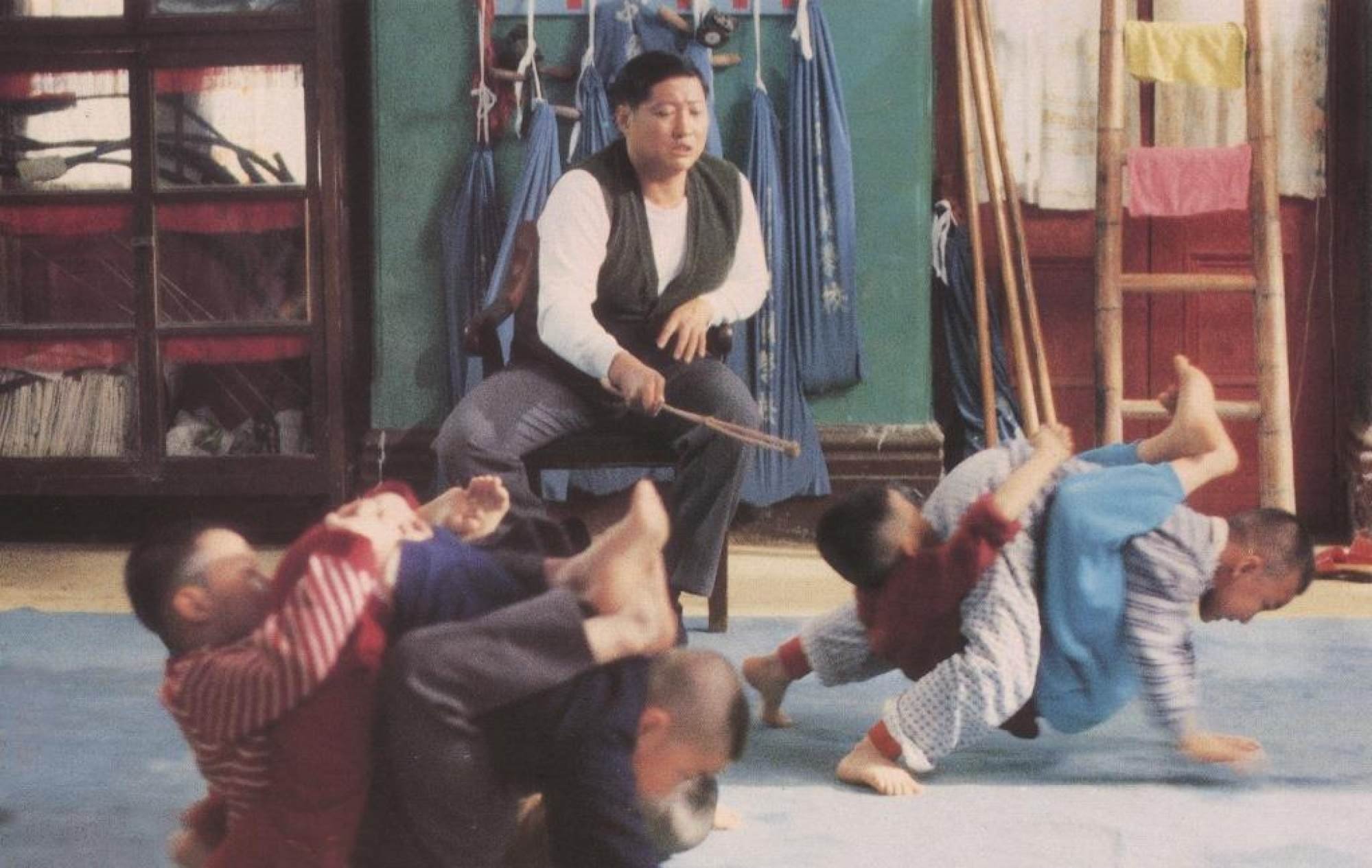

But Yu’s stern, disciplinarian approach to teaching and readiness to resort to a near-sadistic level of corporal punishment turned the wayward child’s life into a living hell.

As Hung and his fellow survivors would later say, it was an extremely common experience to have been beaten on the buttocks by their sifu, or master, with a rattan cane.

When I ask Hung to describe the single most unforgettable aspect of his training days, he says that quite often, Yu would punish all the students when only one of them had done something bad.

In one episode, after Hung had run away from the school for three days and his fellow student Yuen Wah was caught secretly helping him, the latter was beaten 70 times with a cane, and became one of Hung’s best friends in life.

“I still have a scar on the top of my head from those days,” says Hung, before explaining how one of Yu’s exercises required his young protégés to hold a handstand for more than an hour.

When Hung was “13 or 14”, he says, with his “two feet leaning on a wall, I was standing with my two hands on a wooden bench for one and a half hours. It’s no joke, you know?

“At some point, I was completely exhausted. I fell down and my head hit the bench. Blood came streaming down my face, and I remember thinking, ‘Why am I sweating so much? Is the weather that hot?’ But it was all blood.”

In it, the filmmaker cast his own son, Timmy Hung Tin-ming, to play Yu, and presented what can only be described as a rose-tinted view of his coming-of-age period.

“We have many stories – too many – from our training days,” says Hung. “It’s only after the fact that you could see the silver lining.”

Sammo Hung started working as a stuntman in films at the age of 14, and finished his apprenticeship under Yu and became a full-time performer at 16.

The Shaw Brothers production The Golden Sword (1969) marked his first credit as a martial arts choreographer, after Han Ying-chieh – Yu’s son-in-law and Hung’s mentor on his early film shoots – dropped out of the project.

I’ll keep doing my own thing and continue to realise the ideas that I’ve come up with

Sammo Hung

Hung still recalls how, under the summer sun at the Shing Mun Reservoir, in Hong Kong’s New Territories, Hu once spent a whole day doing one close-up shot of an actor looking to the camera above.

“We were all wondering: ‘What’s taking so long?’” he says. (Just a few years later, when he was making his own directorial debut, 1977’s The Iron-Fisted Monk, Hung found himself doing more than 40 takes for a close-up shot of the actor Fung Hak-on.)

Hung and Hu’s collaboration continued on The Fate of Lee Khan (1973) and The Valiant Ones (1975).

“After a day of shooting, Hu would often take us to dinner, and after that we would chat about cinema, about characters,” says Hung. “He would finally send us home at 4am and we’d all wake up at 6am to get back on set again.”

As Hung’s own career took off, the two went their separate ways.

One of the last times Hung saw Hu was in the outdoor car park of a Hong Kong hotel, where Hu got out of his car and, true to form, kept talking under the sweltering sun. Hu invited Hung to join him on The Battle of Ono, which was supposed to be Hu’s American feature debut before he died suddenly in 1997.

Sammo Hung’s 10 best films ranked, from Pedicab Driver to Ip Man 2

Sammo Hung’s 10 best films ranked, from Pedicab Driver to Ip Man 2

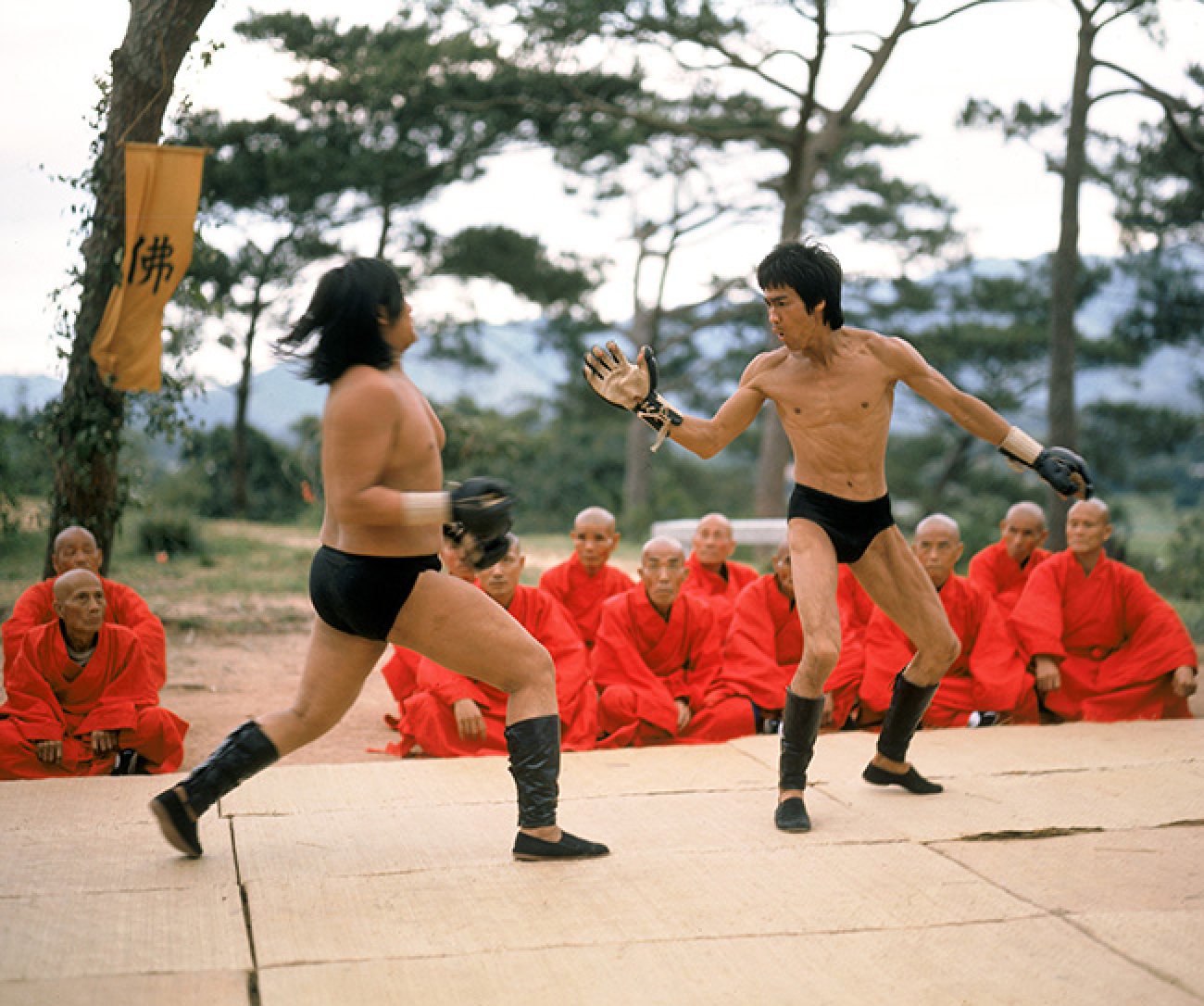

Hung was working as the martial arts choreographer on Thunderbolt (1973) when Lee came on set, inside the Golden Harvest studio, to visit some people.

“He had no idea who I was,” says Hung of their first encounter.

The ensuing turn of events – “not fighting, just a friendly match” as Hung puts it – sounds like it might as well have been taken from a martial arts pulp fiction.

As he recalls: “I said, ‘He’s awesome.’ Lee must have heard and misunderstood, because he immediately went, ‘And so? Wanna fight?’ I was like, ‘OK.’

“Before I’d raised my leg to waist level, Lee’s foot was already in my face. So I said, ‘Well done.’”

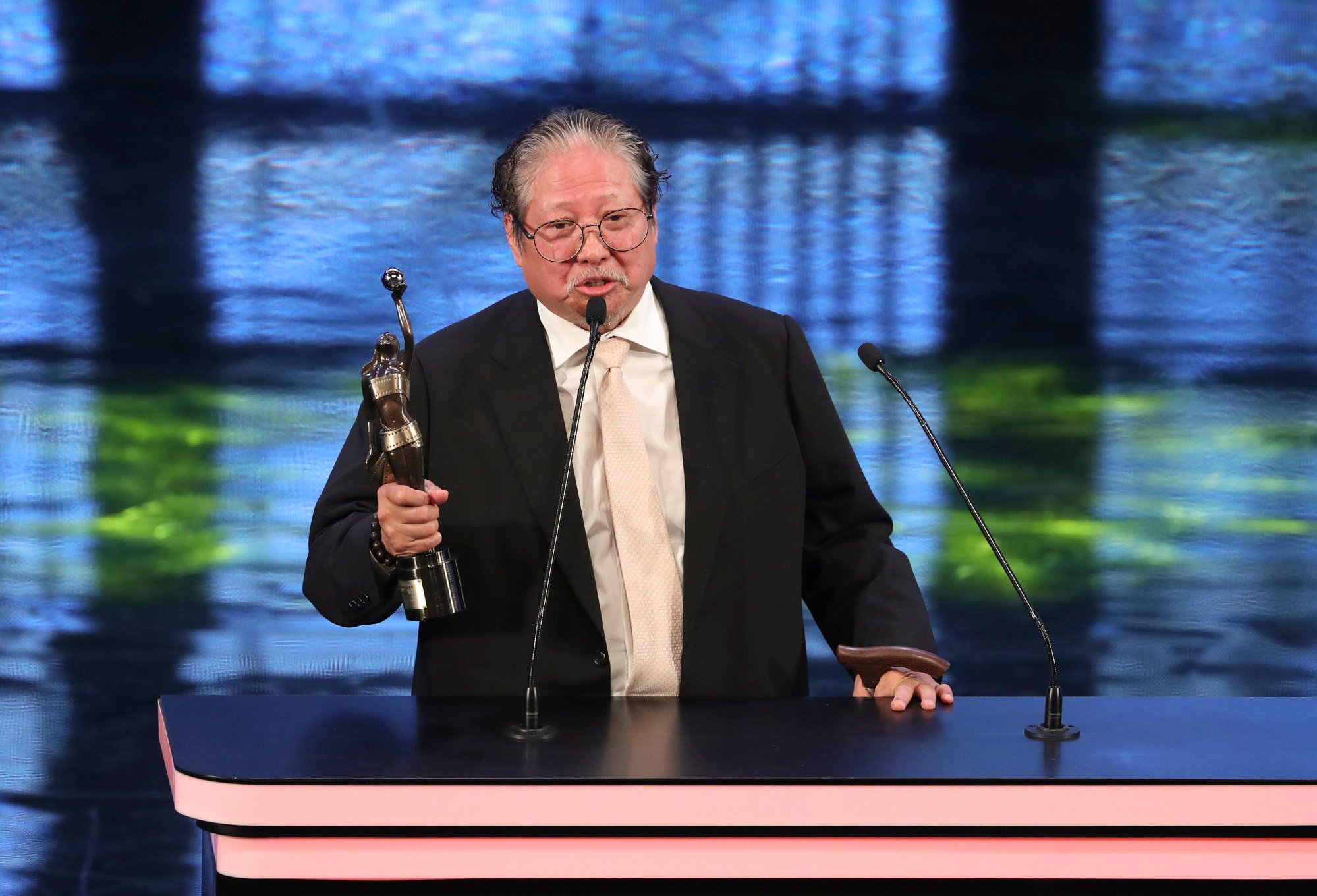

Sammo Hung is one of the most high-profile members of a declining species known as martial arts film stars, but it is no exaggeration to say that he, in his many other capacities, has reinvented Hong Kong cinema several times over.

“It’s related to our personality,” Hung says of the duo’s signature brand of action comedy.

“But it’s also down to the martial arts abilities we learned from our training days, the skills we knew, the moves we could do – these were all parts of our arsenal. Not everyone could do what we did.”

Looking back, Hung says he was surprised by every film that became a hit, “because when I made each of them I was merely guessing what would become successful. I was only thinking, ‘This is a nice gimmick,’ or ‘I think the audience will enjoy this.’”

Apart from being her regular co-star, Hung choreographed Mao’s fight scenes in some of her biggest hits, such as Hapkido and Lady Whirlwind (both 1972).

When I ask Hung specifically about Yeoh, he says, “She’s a very hard-working person; she has put in a lot of effort. I think behind every successful person there’s a story of hard work.”

I don’t really think too much about money. As long as I come across an idea that is good

Sammo Hung

Of Yen, who arguably joined the A-list with his Ip Man role, Hung quips, “There’s no point evaluating his career now – are you even allowed to say anything bad about him? Yen is such a big star. There’s no need to say anything more.”

When I ask Hung if he still remembers the first time in his career he felt he had succeeded, he says, “It’s difficult to say.”

But then he adds, “After I made Encounters of the Spooky Kind, some people who had watched it early said to me: ‘How could you expect a film like this to succeed? You have no chance!’

“And then the film came out and took the box office by storm and those very same people said, ‘See? I knew from day one that your film would be a big hit!’”

Hung pauses for a second to let his listeners’ laughter subside. “So I just let others talk. I’ll keep doing my own thing and continue to realise the ideas that I’ve come up with.”

Which is all well and good – except that Hung has sneaked this admittedly effective gag into every other in-depth interview or public seminar that he has given in the past few years, at times even linking it to different films: The Iron-Fisted Monk is another one that he has referenced with the same punch line.

“Back then, after I’d finished making each film, all I cared about were the moments I got to listen to the laughs in a cinema – that’s when I was happiest,” he says.

In a sense, Hung is as much a great artist as he is a terrible businessman. Acting in the capacity of both a filmmaker and a producer, Hung has long joked, albeit with a hint of truth, that all the top-grossing films he’s made were inevitably for production companies owned by others.

A quick example. In 1987, halfway into the shooting of Spooky, Spooky, a horror comedy being produced and directed by Hung for his own studio, Bojon Films, he received an invitation from Leonard Ho Koon-cheung, of Golden Harvest, to come up with a Lunar New Year release in just a few months’ time.

In a move that made no sense to anyone except Hung, he shelved his own production and accepted Ho’s offer. The resulting film, Dragons Forever, was completed within three months and proved a major blockbuster over the Lunar New Year period in 1988.

Meanwhile, Hung lost what he estimated to be around HK$8 million on Spooky, Spooky due to lapsing contracts in the intervening months.

“I always lose money whenever I play the boss, so no more of that for me,” says Hung. “I can’t say if I’m an artist or not, but I do have a lot of ideas.

“I don’t really think too much about money. As long as I come across an idea that is good, is new, is entertaining to the audience, and is exciting, I’ll try my best to make it happen.”

Michelle Yeoh’s mentor, Jackie Chan’s boss – the many sides to Sammo Hung

Michelle Yeoh’s mentor, Jackie Chan’s boss – the many sides to Sammo Hung

It should not have come as a surprise that eating turns out to be the only running motif in our conversation.

Early on, when I ask Hung to revisit his earliest memories as a child actor, he replies, “The memories included: ‘Were we full after eating?’ ‘Did we have anything to eat?’

“That’s what we thought about as kids. We trained together and we ate together.”

Without prompting, he tells me of the time he and a senior apprentice were working on a film; during meal times, the two would go to a particular restaurant that charged HK$1.20 for a dish with all-you-can-eat rice.

“I ate nine bowls of rice and my sihing [“elder brother”] ate eight,” says Hung proudly, pointing out that the bowls back then were considerably larger than the ones we use today.

“The restaurant owner ended up kicking us out and telling us never to come back again.”

The theme would go on. What’s he been up to? “Busy buying groceries and cooking dinners.”

What does he enjoy the most on a film set? “The moment of calling: ‘Meal time!’ I find the food especially tasty on set.”

Will he train a new generation of action actors? “Not if they’re going to end up selling char siu bao for a living.”

Does he exercise? “Yes, with my upper lip and lower lip when I eat!”

I have a lot of things to say [about the state of Hong Kong cinema], I just don’t have the courage to

Sammo Hung

Regardless of all the talk, Hung is, in person, both fitter and frailer than his former burly self. Occasionally, there is a wistful tone that suggests things may be slowly winding down – for both Hung’s career and the filmmaking environment that rendered that a possibility in the first place.

As a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic, Hung’s much heralded stunt team is, after decades of operation, no longer active.

While his fans will soon be able to see him on the big screen, in director Soi Cheang Pou-soi’s mega-budget action epic Twilight of the Warriors: Walled In, set for a May 1 release in Hong Kong, Hung says he has no imminent film projects to work on. He is “unemployed”.

Hung says he is “pessimistic, very pessimistic” about the state of things. “I have a lot of things to say, I just don’t have the courage to.”

Whatever the state of Hong Kong cinema, Hung has been around long enough to be able to look back with equanimity.

And while he admits he uses a cane for short walks, and a wheelchair for longer ones, his room service Caesar salad and minestrone soup have been getting cold for an hour.

At what looks to be a late-stage diet move for the notorious calorie-consumer, he shrugs: “I don’t want to be around for too long,” then after a second, “30 or 40 more years would be enough for me.”