“The man and woman, aged between 20 and 25, were discovered lying on a rock among undergrowth. The man had his hands tied behind his back and was gagged, while the woman had a tie around her neck.”

The police had difficulty investigating the case. At first they arrested a “grave exhumer”, the Post said. But he was released after being made to swear his innocence in front of a statue of Kwan Ti, the god of war – a procedure that led to much controversy.

Man on the Brink: the original Hong Kong undercover police drama

Man on the Brink: the original Hong Kong undercover police drama

Later reports said that the man who was finally arrested for the murder – rubbish collector Chan Yiu – was only caught after a blessing ceremony was performed at Western Police Station, a ceremony which involved offerings to, again, Kwan Ti.

Chan was found unfit to stand trial for the killings as he was mentally ill, and he was incarcerated in a mental hospital.

While that sounds like a great story for a movie, Hui and her scriptwriter Joyce Chan Wan-man actually filmed a completely different story that only took a few cues from the real event.

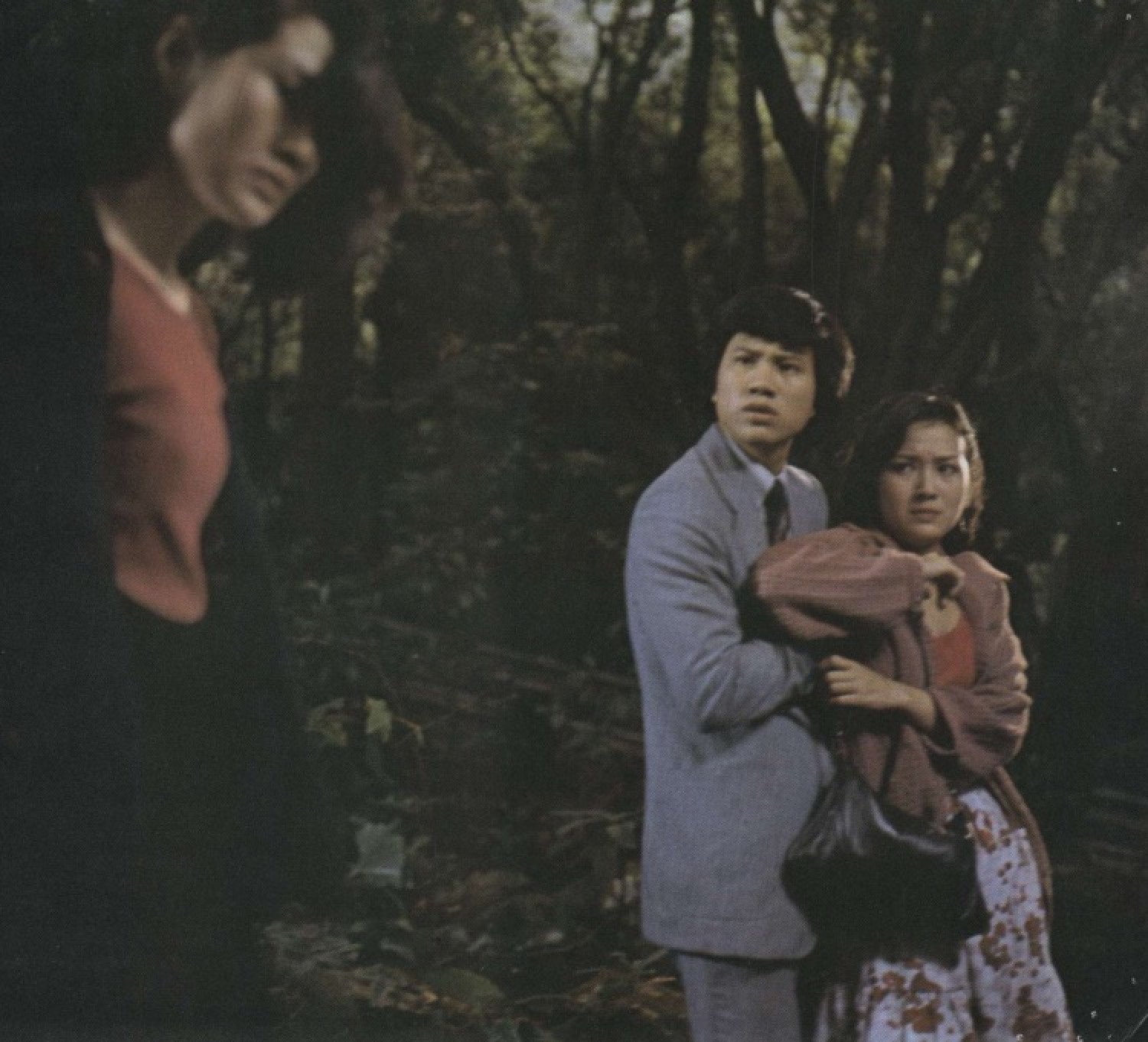

In the film, the murdered couple – renamed Li Yuen (Angie Chiu Nga-chi) and Yuen Si-cho (Alex Man Chi-leung) – are discovered in the woods in Pok Fu Lam by some boys, who report them to a police post.

Yuen, the man, is identified at the morgue. But Li’s blind grandmother and her relatives do not properly identify her – distraught, they give a positive ID on the strength of a lai see envelope that has been found on the corpse.

Li’s friend and neighbour Lan (Sylvia Chang Ai-chia) becomes suspicious when she glimpses someone who looks like Li rooting around her old room late at night. Is it a ghost?

‘This is it’: the 90s film set on which Michelle Yeoh was seriously injured

‘This is it’: the 90s film set on which Michelle Yeoh was seriously injured

Lan takes on the role of an amateur detective to try and find out exactly what occurred on the night of the murder, and a wide array of events neatly dovetail together to form a clever picture of the dark side of the human condition.

Hui, who had studied filmmaking in London, brought more modern techniques and structures to Hong Kong filmmaking with The Secret. The use of flashbacks, for instance, was much more advanced than anything that Hong Kong cinema had seen before. The plotting, too, was extremely ambitious and much more complex than most films of the time.

“What makes The Secret so extraordinary is what Hui chooses to do with her material,” Poshek Fu and David Desser wrote in their book, The Cinema of Hong Kong. “Through creation of image and sound, Hui creates a world suffused with uncertainty.

“Suspense is created by shots of empty spaces, unmotivated camera pans, misty streets, a lone cat crossing an alley, a moving light with no source, and off-screen sounds of high heels, all seen and heard against eerie organ music. Together, the elements create an atmosphere of the supernatural.”

Hui and her cinematographer David Chung Chi-man used many tropes from the horror and ghost genres, and the occasional scene veers towards the grotesque – some shots of a dissection in the morgue, and the actual murder sequence, for instance.

How early Patrick Tam and Ann Hui films show Hong Kong New Wave’s diversity

How early Patrick Tam and Ann Hui films show Hong Kong New Wave’s diversity

The Secret is forward-looking and modern in attitude – superstitions are seen as manifestations of a conservative past that constrains the characters, rather than pleasant nostalgia.

“There are no ghosts in the film, although it is terribly ghostly,” wrote critic Sek Kei in his essay “The Wandering Spook”. “The Secret tells a story of passion and murder. The ‘murdered’ female victim is, in fact, quite alive. Is she human, or a spirit? Who is the victim and the victimiser? A web of questions are intricately weaved.

“The contradictory attributes of East and West, the new and the old, are displayed in The Secret like a labyrinth and very graphically represented.”

It is worth noting that The Secret’s strong focus on the reality of Hong Kong life and culture was unusual for the time.

During the late 1960s and ’70s, the martial arts films that ruled the box office had focused on mainland China. In previous decades, contemporary-set dramas had generally been vehicles to instil conservative Confucian values into viewers.

But The Secret depicted modern Hong Kong attitudes – and locations – that viewers could recognise.

“Social touches are richly enhanced by the on-location shooting, a New Wave practice enhanced by the social realist approaches of 1970s television,” wrote film historian Sam Ho in his essay “Invigorating Contradictions”.

In hit film Boat People, Ann Hui tried to explain refugees fleeing Vietnam

In hit film Boat People, Ann Hui tried to explain refugees fleeing Vietnam

The film managed to depict the many contradictory sides of Hong Kong life, and the tension between the old and the new. It is also an early example of a woman director’s film in Hong Kong.

Women directors like Hui were rare in Hong Kong cinema, which was a male-dominated industry. The Secret also had a female screenwriter, the well-regarded Chan, who had collaborated with Hui on many of her TV works.

The film’s star, Sylvia Chang, owned the production company Unique Films, and Selina Chow Liang Shuk-yee, the executive who encouraged the New Wave filmmakers when they worked at local broadcaster TVB, was also involved with Unique.

The storyline focuses almost entirely on the women characters – the men are consigned to the sidelines.

The film’s central theme about how the strictures of male-oriented Confucian morality could lead to disaster – the crimes are committed because a female character is trying to hide her out-of-wedlock pregnancy – was also new, and represented issues that modern women faced in patriarchal Hong Kong.

Despite being such an important work, it had been very difficult to see The Secret outside special screening programmes in Hong Kong.

Elegies: Ann Hui documentary on poets is her subtle lament for Hong Kong

Elegies: Ann Hui documentary on poets is her subtle lament for Hong Kong

As with many local classics, the prints were either lost, or destroyed. The Hong Kong Film Archive restored The Secret in 2017 using recently found footage. Betacam and VHS tapes had to be used to fill in some missing scenes and to replace the dialogue track. The film is now restored and available to see in its full glory.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.