Ever since the turn of the century and the IT boom, the BJP has got the better of the Congress and the Janata Dal (Secular), or JD(S), in the elections to Lok Sabha, assembly and even the municipal corporation (Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike), retaining a firm grip over the city’s administration and its votes.

Analysts say that Bengaluru largely skips caste barriers and caters to an ‘aspirational’ class looking to benefit from rapid growth and may not be very concerned about trends that are developing — or, persists— in other parts of Karnataka.

A significant section of Bengaluru’s migratory workforce — both blue and white collar — do not resonate with local issues like caste but consider more economic arguments like employment and business environment, they argue.

“Many urban dwellers or upper middle classes are into share market investments, business….and as long as it is going up, they may not be very bothered about social or economic inequality around them or in other parts,” said a former faculty member of the National Law School.

The voting patterns for state and central elections are different as well. So, a vote for the Congress in the 2023 assembly election is no guarantee of a repeat in 2024.

The Congress, the analysts say, is trying to get to the antithesis of this trend, hoping to attract votes of the urban poor who it believes have benefitted from its guarantees of free public bus travel (Shakthi) and Rs 2,000 per month for women (Gruha Lakshmi), free rice (Anna Bhagya), subsidised food ventures (Indira Canteen), free electricity (Gruha Jyothi), and financial assistance to unemployed youngsters (Yuva Nidhi).

The BJP, on its part, hopes that the city will continue to vote for PM Narendra Modi, irrespective of the candidate. Its IT cell is targeting voters through social media platforms, often tapping on nationalistic sentiments and global pride.

Even though there is general disdain for lack of development, the city has also become synonymous with voter apathy. Bengaluru recorded the lowest voter turnout of just over 54 percent in the 2023 Karnataka election, as against the state average of around 74 percent.

All four seats in Bengaluru will vote on 26 April.

Also Read: In Karnataka, a ‘khadi vs khavi’ battle as head of Lingayat mutt takes on BJP’s Pralhad Joshi

Guarantees vs development

Often termed as ‘freebies’, the five guarantees are estimated to cost Rs 60,000 crore annually, which Bengaluruians believe could have been used to fix the city’s crumbling infrastructure, analysts say.

Narendar Pani, faculty at the National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS), says that Bengaluru has resisted any attempt to divert money earned through the large services sectors such as IT.

“If you try to return some of it back to the rest of the state, whether through guarantees or other programmes, there is a huge resistance from Bengaluru. And that is something that the BJP plays up and taps,” Pani says.

The BJP has repeatedly attacked the ruling Congress over its guarantee schemes, directly linking them to Karnataka’s dismal fiscal condition. On its part, the Congress has accused the Modi government of not releasing grants, aid for drought and the ‘step-motherly’ treatment to Karnataka.

On Monday, Bangalore South MP Tejasvi Surya said that in the last five years, Bengaluru has got Rs 1.3 lakh crore worth of projects from the Modi-led government.

Though the party is relying heavily on ‘Modi-magic’, it is also being cautious, reaching out to caste groups, people from diverse backgrounds and the largely migrant workforce, BJP leaders say.

The BJP won 25 out of the 28 Lok Sabha seats in 2019 but has seen an outburst of rebellion over ticket distribution, overlooking seniors and other fault lines that threatens to break its stronghold in the city.

In Bengaluru North, B.S.Yediyurappa’s close aide Shobha Karandlaje was made the candidate despite the protests against her in Udupi-Chikmagalur over lack of development. Karandlaje replaced D.V.Sadandanda Gowda, who has since taken a vow to ‘cleanse’ the BJP of ‘dynasty politics’.

The Congress, on the other hand, has relied on sons and daughters of existing or former ministers to bag seats.

Mansoor Ali Khan, the candidate in Bengaluru Central, is the son of former Union minister K.Rahman Khan. Former Karnataka speaker M.V.Venkatappa’s son Rajeev Gowda is contesting from Bengaluru North.

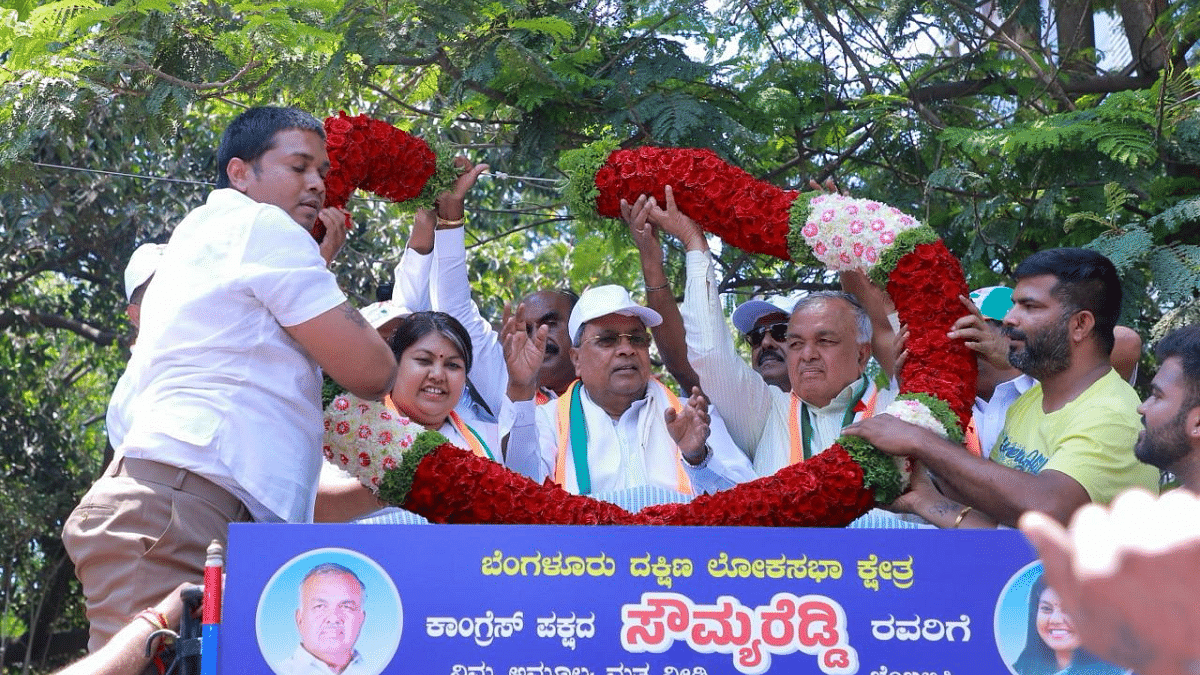

Bangalore Rural sitting MP D.K.Suresh, the brother of Deputy CM D.K.Shivakumar, is looking to retain the seat. Transport minister Ramalinga Reddy’s daughter Soumya Reddy is gearing up to give a tough fight to Tejasvi Surya. It is also banking on the support of disgruntled BJP legislators like S.T.Somashekar who is openly campaigning for the Congress.

Popularly known by its monikers as ‘IT capital’ or ‘startup hub’, Bengaluru has also seen polarising politics take centre stage like the Hanuman Chalisa campaign, communal tensions during the Covid-19 pandemic-induced lockdown among others, which the BJP is looking to capitalise. The BJP has tried to link the Rameshwaram Cafe blast and chants of ‘Pakistan Zindabad’ to the ruling party’s alleged indulging in appeasement politics.

The city has also become synonymous with crumbling infrastructure and endless traffic jams. Since 2000, Bengaluru has seen exponential growth but development has not been able to catch up as the city is riddled with problems like shrinking spaces, erosion of lakes and green cover, crumbling infrastructure, unbearable traffic and rising temperatures.

But the BJP, which has held power in the state, centre and the civic body, has made little difference to voting behaviour. As rapid urbanisation and overexploitation of resources exacerbate the city’s problems, Siddaramaiah is trying to pin this on the BJP administration — or, the lack of it to corner votes for the Congress.

“Cauvery connection for drinking water needs to be increased in Bengaluru South. Now it is only 60 percent. Soumya Reddy’s victory is essential if the Mekedatu project is to be implemented,” Siddaramaiah said at campaign Monday.

Landed class & IT workforce

Prior to the 2008 delimitation exercise, Bengaluru had just two seats — North and South. In the 1989 Lok Sabha election, Jaffer Shariff and Gundu Rao won both seats in Bengaluru, the last time the Congress won in both seats.

K.Venkatagiri Gowda of the BJP won in Bengaluru South in 1991. Since then, Ananth Kumar held the seat until his death in 2018.

Since 2004, the BJP has won all elections in Bangalore North. The story has been the same in Bangalore Central ever since it was carved out from Bangalore North and South in 2008.

The only challenge the BJP have faced is in Rural, which includes part of the urban constituencies. Former CM H.D.Kumaraswamy of the JD (S) won here in 2009 and since then, it has remained with D.K.Suresh.

Meanwhile, Shivakumar, the state Congress president, has taken it upon himself to defeat the BJP-JD(S) alliance in Bengaluru, mobilising support for the party candidates.

Pani, the NIAS faculty, said that the BJP has targeted IT workers and the landed-classes in the past but the Congress is now trying to separate the two.

Vokkaligas and Reddys are the two prominent landowning classes in the city, and Ramalinga Reddy is mobilising both in Bangalore South. Surya won a landslide victory in 2019, but he is a Brahmin.

The BJP has similar challenges in other seats as well, Bengaluru-based political analyst Sandeep Shastri said.

P.C.Mohan is contesting for the fourth time from Bangalore Central. JD(S) patriarch H.D.Deve Gowda’s son-in-law C.N.Manjunath is contesting on a BJP ticket in Bengaluru Rural.

“All four (seats) are interesting fights and I don’t think the BJP can take any of the four (seats) for granted,” Shastri told ThePrint.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Why Tejasvi Surya is not in BJP’s list of Lok Sabha star campaigners, 2nd time after Karnataka polls