The malaria of the title is probably not malaria as we understand it today. In fact, apart from a few official medical references, people at the time rarely used that word.

In 1843, when the city – really more of a ramshackle town – was blighted by illness, it became known by the catch-all “Hongkong Fever”; in 1848, it was called “barrack fever”.

“‘Marsh miasma’ was another term,” agrees Cowell, cheerfully. “It was ‘bad air’, which is what mala aria means.

“The interest for me is not what it is, it’s that it had a strange agency. It threw itself into the planning of Hong Kong and disrupted it.”

Today’s residents may like to know that even then, the local population found the south side of the island more salubrious.

We tend to dismiss doctors from that period as stupid. But they had great acuity in observation.

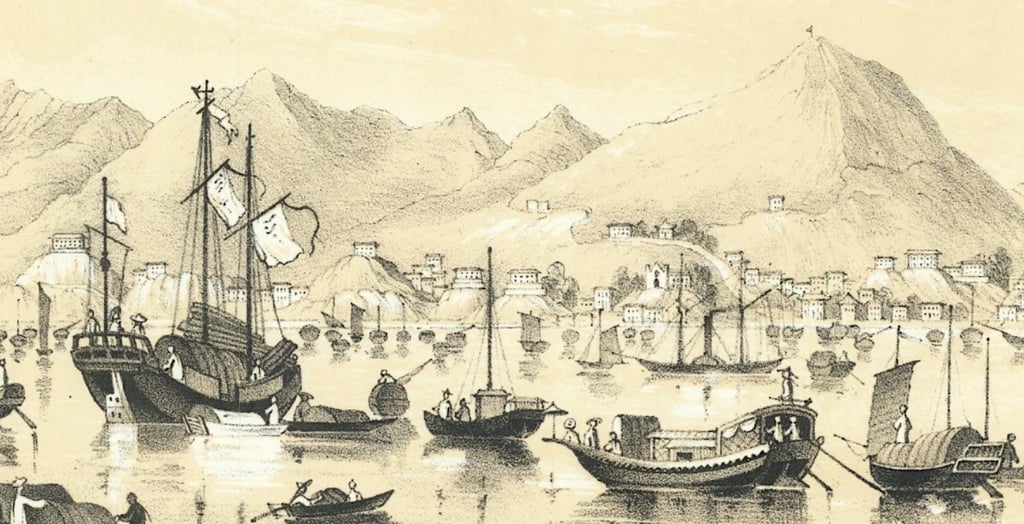

Elliot had arrived in January, a dry, cold month. As the winds and weather shifted, however, sickness set in. By August 1842, Sir Hugh Gough, the head of the expeditionary land force, was writing to Sir Henry Pottinger – then Hong Kong’s second administrator, later its first governor – that he was convinced the north side “will never be healthy during the hot and wet season”.

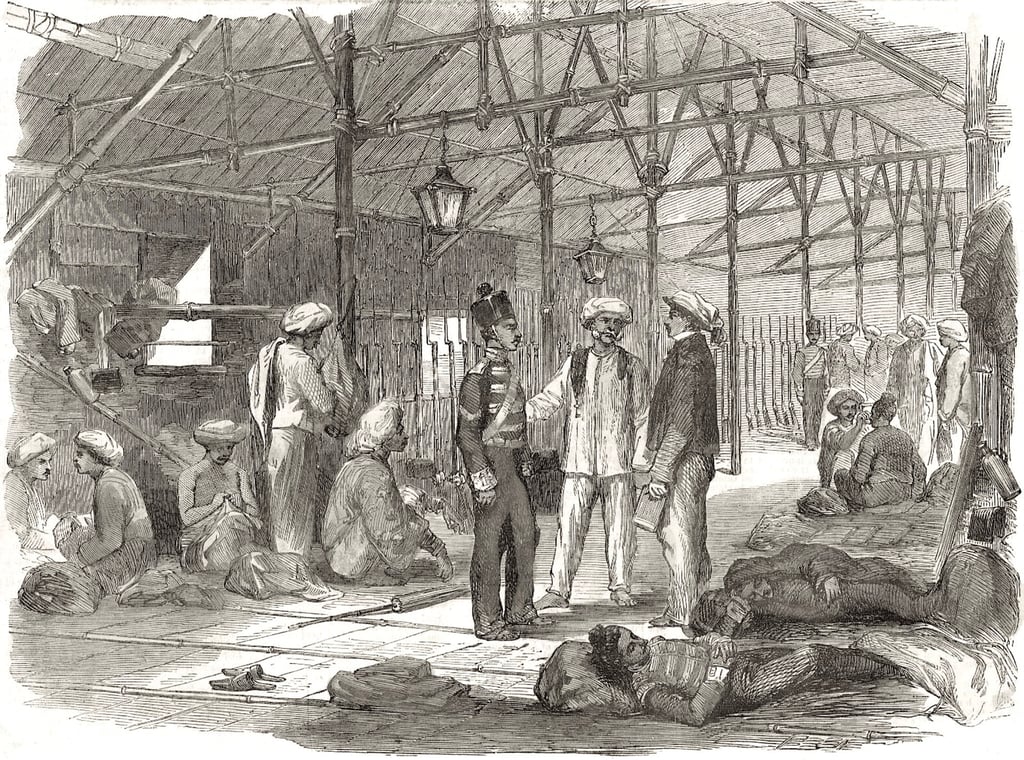

But the British were already building roads, churning up mounds of soil that would later be used for reclamation. Land auctions had also begun. Purchasers were obliged to construct a property within six months, so speed was of the commercial essence.

As a result, pools of stagnant water formed in the disturbed, abandoned earth. Mosquitoes, considered irritating but not deadly, moved in; they would not be identified as the fatal transmitters of malaria until 1897. In the subsequent 1843 fever, about 24 per cent of the military garrison and 10 per cent of the European civilian population died. The city began to seek higher locations.

Reading Cowell’s book with 2024 wisdom, one winces at contemporary speculation about cause and effect: lightning? A magnetic force in the rock? Rotting vegetation? A poison concentrated along the island’s surface?

“One of the things I wanted to emphasise is we tend to dismiss doctors from that period as stupid,” says Cowell. “But they had great acuity in observation; they were trained in geology, in weather, in climate.”

It was an 1845 medical report, with a paragraph stating that the fever was caused by “bad building, bad construction and damp ground”, that triggered his interest.

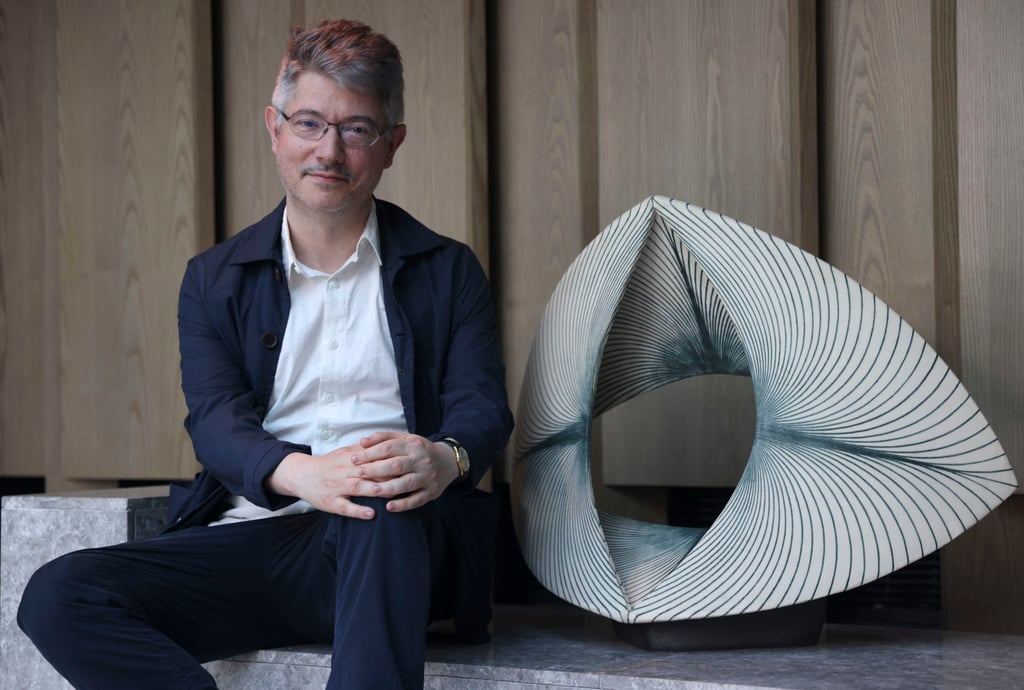

Cowell had arrived in Hong Kong in 1996 to work as a young architect on the Hong Kong MTR station. Later, he became a senior research assistant at the University of Hong Kong and in 2006, he began his Master of Philosophy thesis.

He had intended to write about the Corps of Royal Engineers but reading that brief report encouraged him to combine history with urban design.

I think at the beginning I was more nonchalant. But my time in America made me more critical of colonialism.

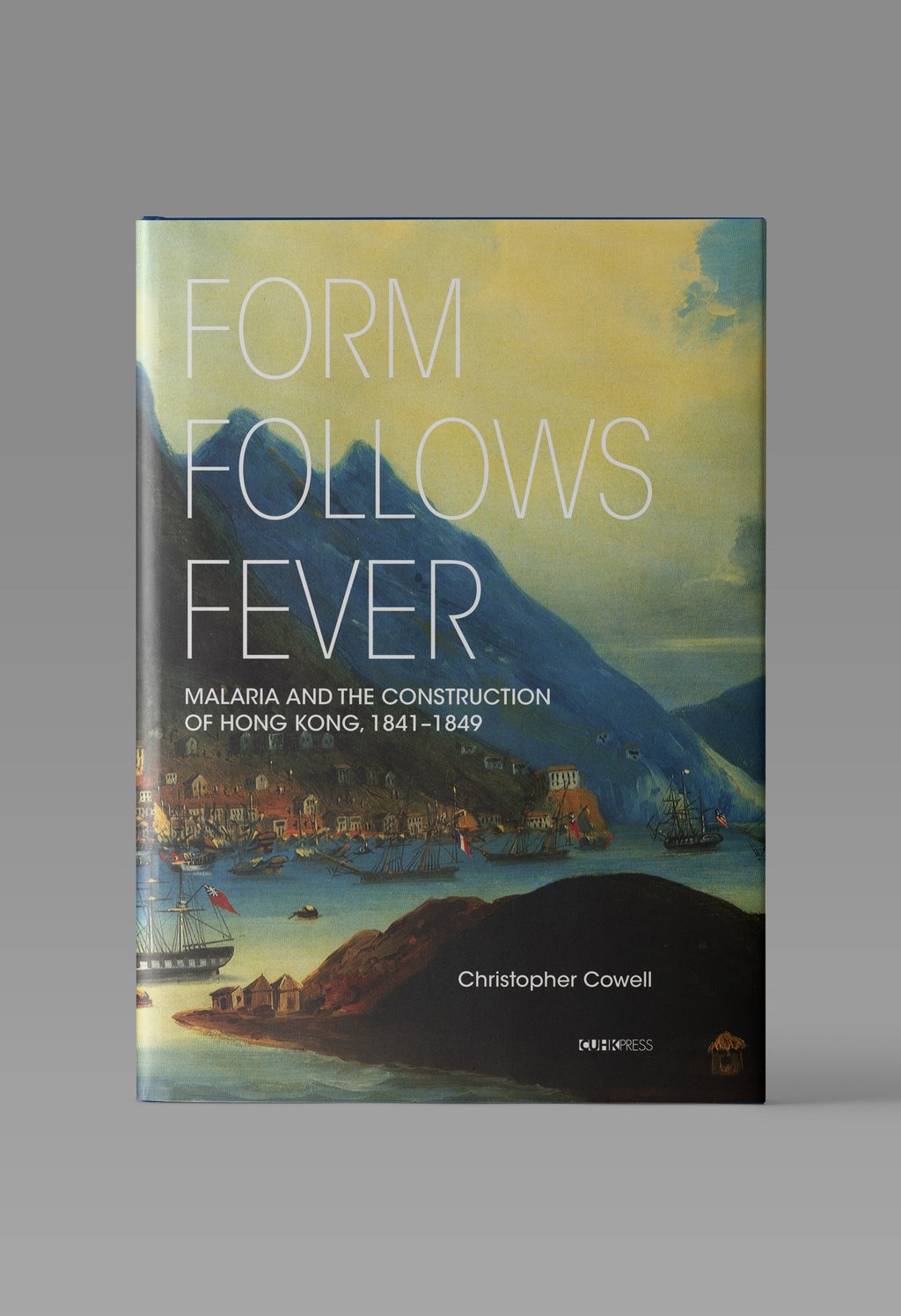

His 2009 MPhil title was Form Follows Fear: Malaria and the Making of Hong Kong, 1841-1848. You will spot the overlap. (Despite his love of alliteration, he had to jettison ‘making of’ because it has featured so often in recent Hong Kong titles; and he extended the timespan by a year.)

When he presented his candidacy, he told the examiners that HKU’s Department of History, then in the courtyard of the university’s Main Building, was where the latrines at West Point barracks – Ground Zero for the 1843 Hongkong fever – had once been sited.

The army subsequently marched – or staggered – out to seek a healthier location and the only clue it had ever been there remains in the Chinese name for West Military Camp: Sai Ying Pun.

After Hong Kong, he acquired a PhD at Columbia University, in New York, and now teaches at London South Bank University.

Cowell had always intended his thesis to become a book. Fifteen years ago, he had already chosen the cover image: an anonymous painting of Hong Kong Island from c. 1843 with, he writes, “a sickly hue of bile-ish greens, mouldy blues, and a jaundiced sky”, which may be more of an indication of his determination to remain on topic than the artist’s intention.

Other illustrations – including the world’s first printed map with contours and some remarkable drawings of the city’s construction with mat sheds – have been lavishly reproduced by The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

The book’s emphasis on colonial architecture and urban design is described in the introduction as a “new strand” in CUHKP’s catalogue.

This was, appropriately enough, a pandemic project. At the same time, his attitude towards the British Empire was changing. “I think at the beginning I was more nonchalant,” says Cowell.

“But my time in America made me more critical of colonialism. The tone has got more hard-edged.”

The text reproduces a suicide note by a debt-laden contractor, Achou, who hanged himself in January 1846. Some of the European community felt that the workers should have a day off; but that was in order to keep the Sabbath day holy.

Curiously, what comes over most is the hurry-up-and-wait atmosphere of those early years. The military, the merchants and the civilian government worked feverishly – sometimes literally – but their intentions weren’t aligned.

Kowloon exerted a force, it sat there teasing the settlers

“I don’t know any other examples of a founding-colonial story where the founders don’t want to found,” says Cowell. “They’re setting it up but they’re not sure they want it. They could use it as a bargaining chip to get another place, maybe get back into Canton.”

Across the harbour, however, there was a tract of land called Kowloon. There were two Chinese forts on its tip; the British nicknamed them Victoria and Albert. These were demolished and their bricks were used in the early building of Hong Kong.

But Kowloon – sunny, flat and, somehow, apparently healthy – was not British territory and until Britain controlled both sides of the harbour, there could be no ease.

“They needed both bookends,” as Cowell, who is speaking at the Hong Kong Book Fair on July 17, aptly puts it. “Kowloon exerted a force, it sat there teasing the settlers.” Picnic tours to Kowloon side were illegal but became, as he writes, “a flagrant habit of the British”.

He ends his book with one such picnic in March 1848, actually organised by the chief magistrate, Major William Caine – a foreshadowing of what was to come.

Form Follows Fever: Malaria and the Construction of Hong Kong, 1841-1849 is published by CUHK Press