One of Leung Hing’s children recalled that, being the tallest, Hing was often called in for help by his compatriots.

As in the United States, Hing noticed how docile and timid his fellow Chinese were in the face of the bullying and aggression they suffered. He ventured that the reason could be that the Chinese did not know the local language and so were unable to speak back.

At the turn of the century, an American missionary in China observed that: “The Chinese dislike fighting, although they do not readily yield. Their dislike is not from fear of pain, but because they do not like to be considered rude.

“They are able to bear more pain than we are […] When a Chinese really does lose his temper, he uses very bad language, but he does not come to blows. If the insult or injustice is so great as to provoke murder, he does not kill the other man, but himself, because in doing so the other man is looked upon as a murderer, since he was the cause of the deed.

“They often kill themselves by swallowing poison, after first hiring men to carry their bodies to the door of their enemy.”

Hing was aware that the foreign devils called him and his compatriots cowards, yet he knew that, although his people were more temperate and not as demonstrative as the Mexicans and Americans, they displayed their courage in different ways.

At the gambling table, there are no fathers and sons

Chinese saying

A character trait common to many Chinese migrants, considered a virtue in China, was their forbearance, being able to stand life’s sufferings without complaining or showing any stress or sadness, which were both seen as signs of a weak character. Resentment and negative feelings were then kept repressed within, sometimes until the migrant’s death.

A familiar Chinese expression, conveying that state of mind and used to this day to describe a harsh life, is to “eat bitterness”, which was the lot of most migrants in those days.

Hing’s compatriots generally did not drink, but some had pipes and were addicted to the betting game of fan-tan, which helped distract them from their miseries, and which had been banned by California legislators a couple of years earlier.

During their rare moments of freedom, aside from washing and mending their clothes, they smoked opium or gambled, both of which Hing avoided at all costs, knowing they would make him lose the little money he had managed to save.

Hing knew well the deleterious effect of gambling on his people, thinking of the saying that “at the gambling table, there are no fathers and sons”.

If Hing, like most Chinese, believed in fate and destiny, he did not trust luck, relying all his life only on himself and his hard work. He preferred to spend his free time learning Spanish with the Mexican workers, some of whom had become his friends.

On Saturday nights spent around the fire, Hing enjoyed chatting under the stars, finding strange the feeling of solidarity and fraternity.

In China, he had wanted to put as much distance as possible between himself and anyone who was not from his clan or village, always being on his guard not to be robbed, beaten or kidnapped, as he saw happen to so many of his relatives.

In his overcrowded province people were everywhere, every field was full of labourers, hills were cultivated to their very crests, and pedestrians lined the roads, cities and canal sides. In Mexico, by contrast, he found himself in an empty country full of virgin land.

In 1885, the population of his new country was almost 40 times lower than China’s, its population density almost 10 times less (and almost 20 times less than the overcrowded province of Kwangtung, modern-day Guangdong).

Nonetheless, he and his Chinese compatriots remembered with nostalgia their lives and families back home, their kinship being now their only link to their homeland.

They also discussed their plans for when they would have set aside sufficient money or had had enough of the railroad.

Some thought about working in the mines, others wanted to open their own laundries and asked Hing for advice, many others still dreamed of becoming merchants.

In 1888, after three years of exhausting work and with his first savings in hand, Hing was advised by other workers to try his luck in the trade of goods along the newly opened Mexican railway lines.

At the age of 22, he contacted a San Francisco trading company (via the Sze Yap Company) about obtaining goods that he could easily receive by rail. To get him started, they offered him credit, which he added to his meagre savings, buying his first stock of merchandise.

The whole country of England relies for its livelihood on the trade of its crowd of merchants. There is none who does not look only for profits.

Chinese imperial observer on the practice of deception in trade

Through their family-based credit system, the San Francisco merchants knew Hing’s family address in Hoksaan, and would hold his family accountable for any missing repayments.

In addition, those same merchants were well acquainted with Hing, knowing he had already worked seriously for eight years in San Francisco and Mexico.

This was another important feature of the Chinese diaspora, where each person’s credit was known to everyone else, as within a large family.

Each member of the clan abroad strove all his life to keep a pristine reputation within it, as if he had never left his ancestral village.

One sign of their mercantile mindset was that no product in any Chinese market had a fixed price, everything being always a haggle between buyers and sellers, each carrying their own scales, if not two, to avoid being cheated by the other side.

In the 18th century, having met Chinese travellers in the French court and read the tales of Western missionaries in China, the philosopher Montesquieu suggested that, due to their climate and land, the Chinese could only survive through hard labour and industry, which gave them a great greediness, not tempered by laws, with the result that in China deception was not only widespread but permissible.

The common Chinese opinion, still true today, was that anyone deceived in a business transaction was alone responsible for his loss, for not having shown sufficient caution. Ironically, the Chinese held identical views about Westerners.

An imperial adviser in the 19th century opined: “The whole country of England relies for its livelihood on the trade of its crowd of merchants. Superiors and inferiors compete against each other. There is none who does not look only for profits. If that country has some undertaking afoot, they turn around first to listen to the command of the merchants.”

In any case, Hing found the Mexican markets and stores infinitely less animated and noisy than those in his home province of Kwangtung or even in California, and was surprised at first to find Mexicans so apparently dispassionate about business.

Now that Hing had learned some Spanish, he felt confident about convincing Mexicans to buy his products. Since he did not have enough capital to set up a physical store, he bought himself a suit and became a street vendor, like those in China, going door-to-door between wealthy Mexicans’ homes.

He also decided to cut his pigtail, knowing that he must look as Mexican as possible and that his parents would understand when he returns to China without it.

This made his head feel light and free, and he himself felt different; he could not have imagined that this act would be so liberating.

The Chinese … stand much higher in Mexico than in the United States and in time will be prominent politically and even socially

Liang Cheng, Chinese ambassador to the United States, in 1904

He soon realised that Mexicans were curious about anything Chinese, finding he could earn higher margins by selling Asian handicrafts, which Mexicans had never seen and did not know the real value of.

Hing’s experiences were typical of that era. In the late 19th century, Mexican railroads, mines and large farms developed an organised system of recruitment of contracted Chinese labourers, in collaboration with the Mexican government and the Six Chinese Companies of San Francisco.

Initially recruited to Mexico to serve as contract workers, many later became merchants, small traders, grocers, tailors, laundrymen and restaurant owners.

Long before Mexicans learned to appreciate Chinese cuisine, migrants had begun opening the ubiquitous “Cafes Chinos”, serving bread and snacks. These continued to offer their services in several Mexican cities throughout the 20th century.

Although this was not in the Porfirio Díaz government’s plan, more and more Chinese in the north avoided manual jobs in mining and the railway to focus exclusively on local trade and small businesses, providing daily services to an expanding domestic market, serving not Chinese but Mexican customers.

The transition to small businesses was relatively easy, requiring little start-up capital – usually US$600 to US$800 – often lent by San Francisco merchants.

With a real demand for previously unavailable services, the Chinese quickly found a loyal clientele.

In the United States, the Chinese are restricted to narrow limits for their livelihood, while in Mexico every venue is open

Liang Cheng, Chinese ambassador to the United States, in 1904

Importantly, these small businesses were all transnational, buying their products from Chinese wholesalers located across the border, who travelled regularly to Mexico to supply their clients.

Another advantage was that many merchants belonged to Chinese fraternal societies, buying their products in bulk at near wholesale prices, more cheaply than any of their Mexican competitors.

By 1930, nearly 40 per cent of Mexico’s Chinese had become traders; 20 per cent were farmers, less than 10 per cent worked in industry and only 1 per cent in mining, quite a contrast with the situation of their compatriots in the United States.

With neither capital nor contacts abroad, most poor Mexicans were unable to elevate themselves from their peasant roles in the large haciendas; the Chinese, on the other hand, formed a new petty bourgeois class, mostly in the northern Mexican states, such as Sonora.

The cultures of the early settlers in the US and Mexico stood in stark contrast. The Anglo-Saxon and Eastern European settlers in the US brought a mercantile culture, whereas the early Spanish settlers in Mexico retained an agrarian mindset.

This cultural difference between north and south across the border is still visible today. It meant that Chinese merchants, as well as newly arrived European businessmen, found limited competition in Mexico.

The Chinese were the first to introduce the practice of itinerant trade, door-to-door and village-to-village, which had been unknown in Mexico but widespread in China for centuries.

They sold vegetables, rice and other foodstuffs, not only quickly penetrating the market but also gaining a certain notoriety among Mexicans.

They introduced new sales techniques, such as giving away free products to build customer loyalty, and were also willing to carry large inventories.

The Chinese [in Mexico] receive higher wages than the [local] peons and are everywhere recognised as more valuable workers

Liang Cheng, Chinese ambassador to the United States, in 1904

Like the hated employee stores of large haciendas, Chinese stores also provided credit to customers, thus creating a relationship of dominance and dependence.

While they prospered, they quickly made friends with some of their clients but also enemies among the most disadvantaged Mexicans, who did not understand their rapid success.

At the beginning of the 20th century, 20 years after my ancestors’ arrival, Chinese stores had become ubiquitous in most northern Mexican states.

Two decades later, around 1920, the Chinese had developed a virtual monopoly in small businesses and groceries in the north of Mexico, something that could never have happened in the US on such a large scale.

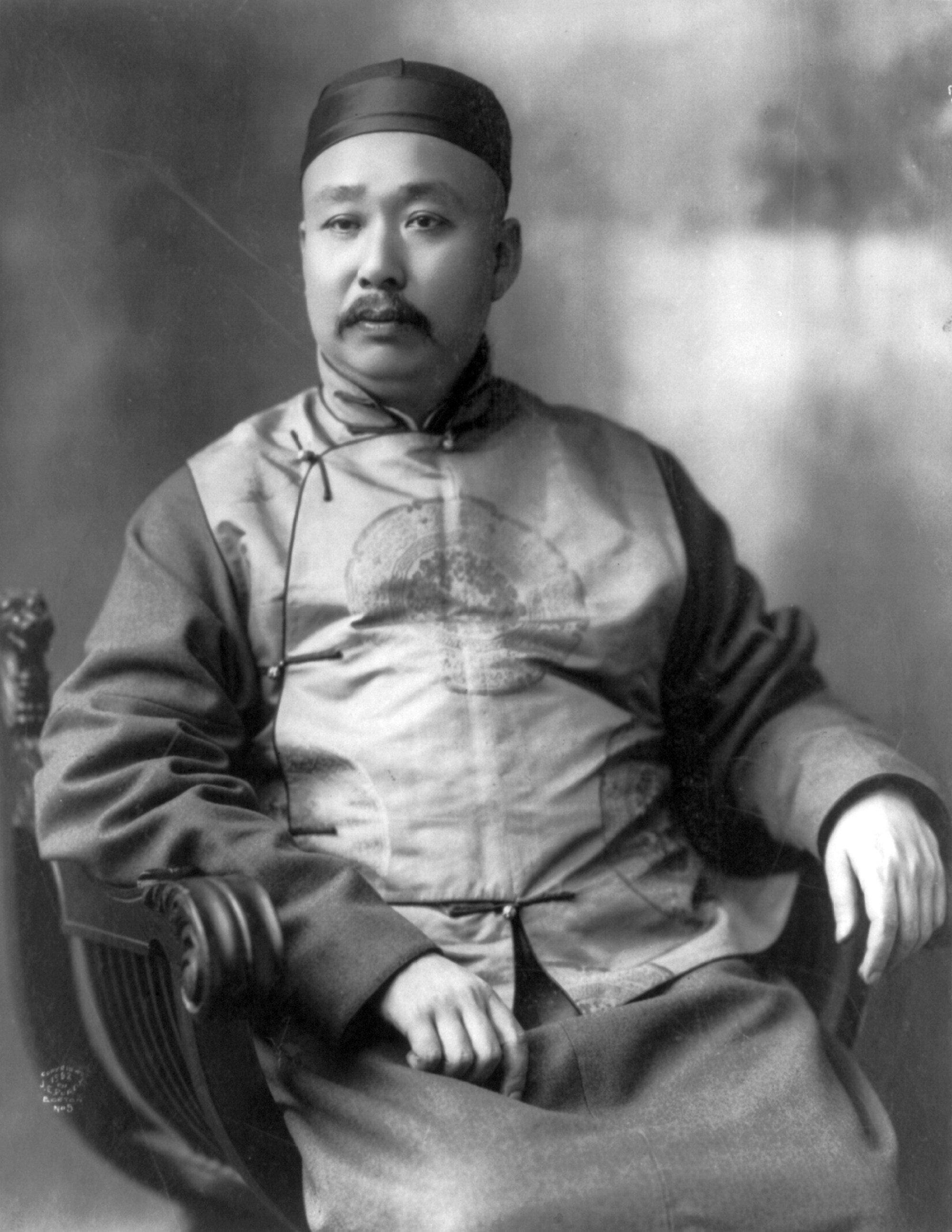

The high level of acculturation of the Chinese in Mexico was observed in 1904 by the Chinese ambassador to the US, Liang Cheng (1864-1917), another Kwangtung native.

Liang had travelled to Mexico on an official state visit and met President Díaz, who told him, “The Chinese are heartily welcome as their industry, frugality and ability are valuable in building up the country.”

Back in Washington, in an article titled, “A Chinese Eldorado,” the ambassador summarised the situation of his countrymen in Mexico: “The Chinese are rapidly becoming a factor in its business life, inclined to become Mexicanized through intermarriage, they stand much higher in Mexico than in the United States and in time will be prominent politically and even socially, the Mexicans being inclined to receive them as equals.

“In the United States, the Chinese are restricted to narrow limits for their livelihood, while in Mexico every venue is open. The Chinese receive higher wages than the [local] peons and are everywhere recognised as more valuable workers.”

Liang belonged to a new generation of Chinese diplomats, who were more familiar with Western culture than his predecessors.

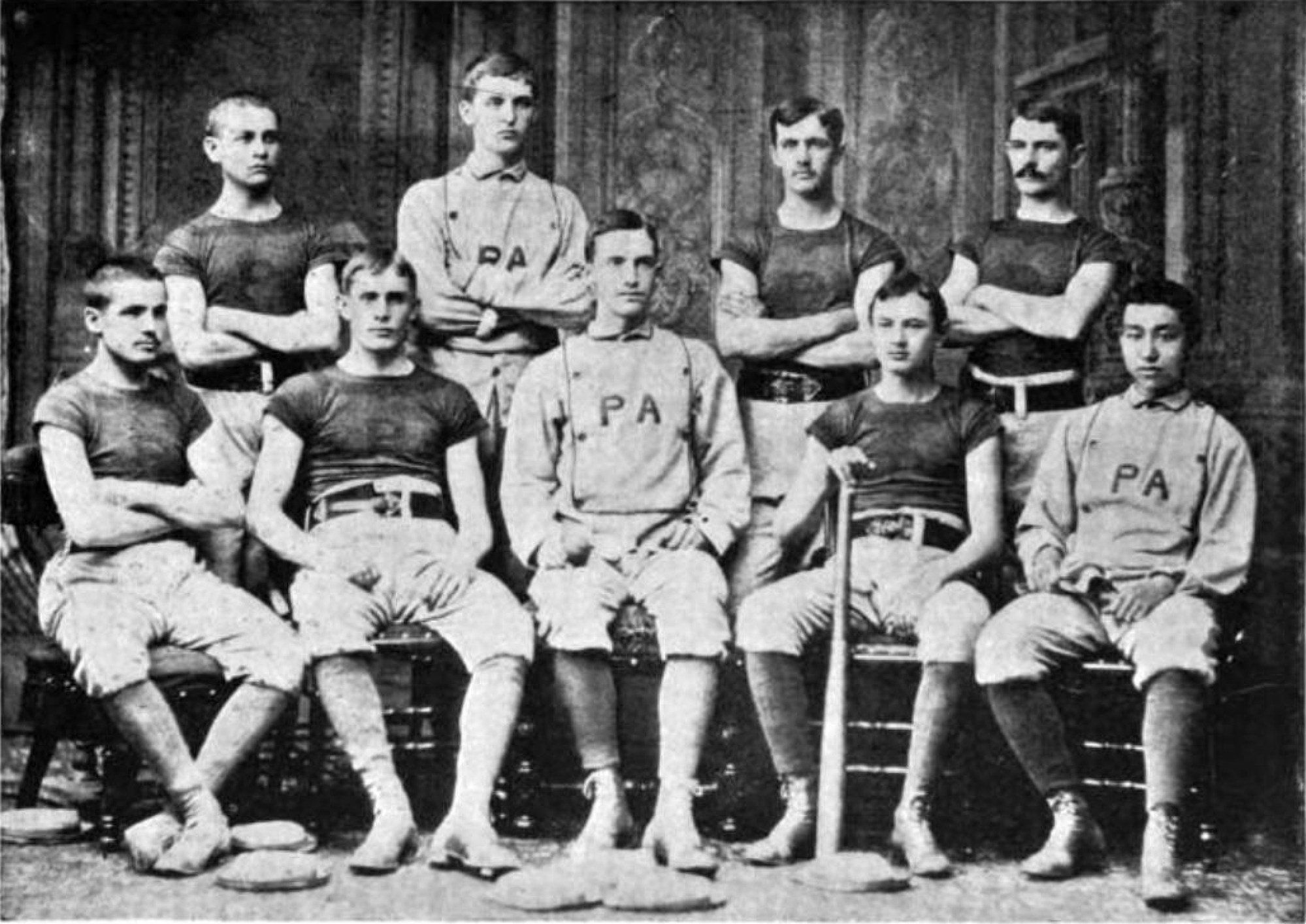

A member of the first group of Chinese students sent to the US, he had attended the prestigious Phillips Academy, in Andover, Massachusetts, where he even became a baseball star.

He was apparently asked by President Theodore Roosevelt, himself an excellent sportsman, about his school days and who was the best baseball player on his school team.

Putting aside his modesty, Liang replied that he himself was, and later reportedly said that, “From that moment the relation between President Roosevelt and myself became 10 times stronger.”

One diplomat was not enough, however, to change the anti-Chinese stance of Roosevelt, who had often been dismissive of the Chinese people, viewing them as an inferior race, calling them Chinks and “poor trembling rabbits”, and tightening the Exclusion Act in 1902.

By contrast, Roosevelt believed that Japan’s strong military was a key indicator of the worth of the Japanese, writing of them in 1905 that they were “a wonderful and civilised people” who were “entitled to stand on an absolute equality with all the other people of the civilised world”.

That same year, Roosevelt brokered the Treaty of Portsmouth, giving Japan free rein to colonise Korea, for which he dubiously received the Nobel Peace Prize.

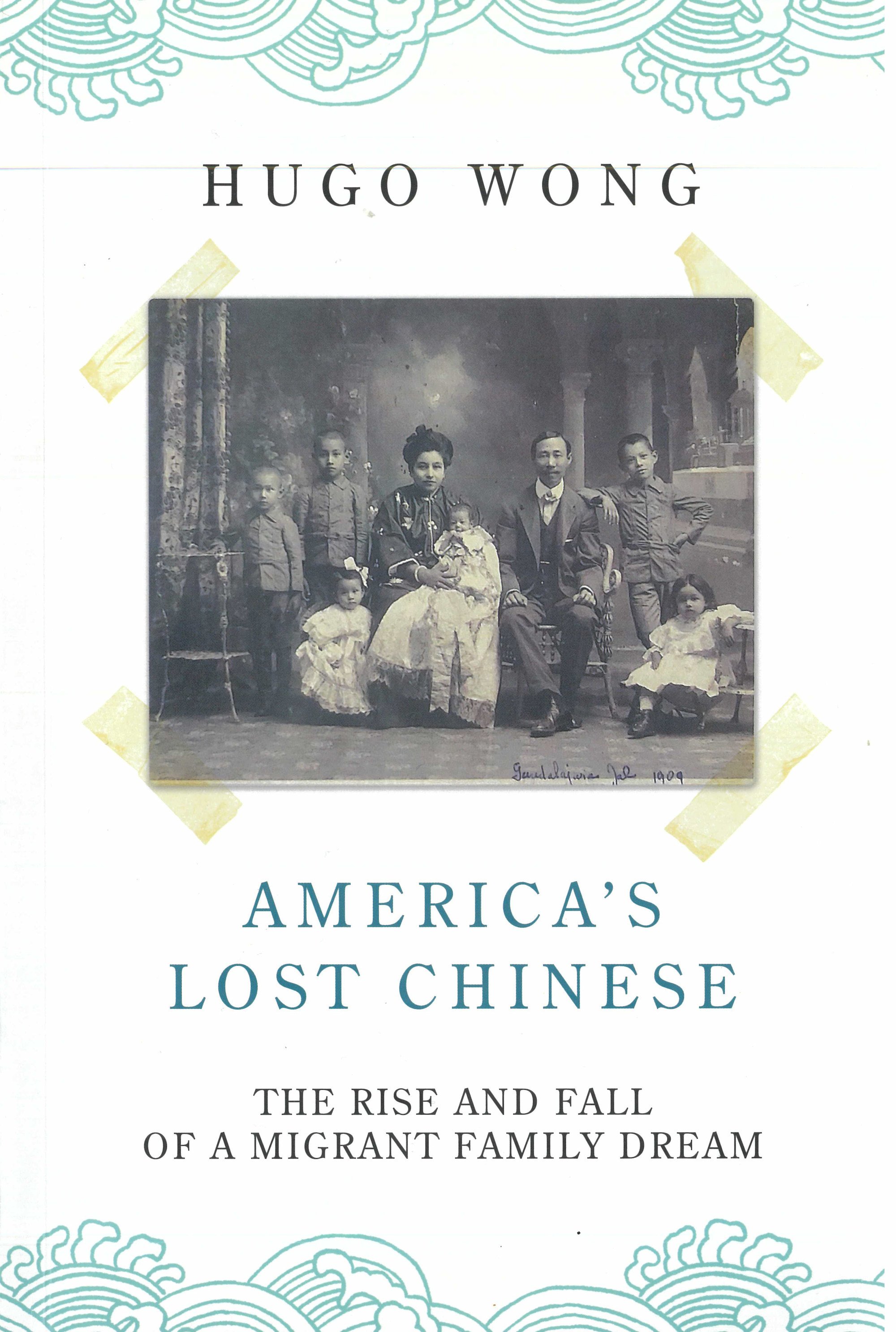

Excerpted from America’s Lost Chinese: The Rise and Fall of a Migrant Family Dream, by Hugo Wong, Hong Kong University Press, 2024.