To understand the potential ramifications of Raisi’s unexpected death on Iran’s domestic and foreign policy, it is essential to examine the country’s political landscape, process of succession, and its broader regional and international relations.

President vs supreme leader

After the outbreak of widespread unrest and mass demonstrations in 1979 – triggered by dissatisfaction with the rule of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi – the Islamic Revolution led to the establishment of a new government in Iran.

Through a popular vote, Iranians chose to become an Islamic Republic, effectively dethroning the monarchy and forcing the shah into exile. This new system transformed Iran into a Shiite theocracy and, that same year, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was elected as the country’s first supreme leader, who had the last word on all matters of state.

The country’s constitution, ratified in 1979 by a popular referendum, features a blend of Islamic theocracy and democratic principles.

Sitting at the top of Iran’s political structure today is supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, 85, who succeeded Khomeini after his death in 1989. Khamenei has final say on Iran’s foreign policy and its controversial nuclear programme.

Raisi was widely regarded as a staunch ally of the supreme leader, implementing his policies and promoting the expanded role of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in both politics and the economy realms, experts say.

As such, not much is likely to change regarding Iran’s major foreign-policy stances because “the president has very little influence” on these decisions, according to Alam Saleh, an Iranian studies specialist at the Australian National University.

“The ultimate decision-maker is the supreme leader, so when it comes to regional and foreign policy, things are likely to stay the same as before.”

Question of succession

Given Khamenei’s age, the question of who will become the country’s next supreme leader is the subject of much speculation. Raisi was considered by some to be a potential successor, but analysts say his prospects were limited, particularly because he was in competition with Khamenei’s son, Mojtaba, an Islamic cleric who already works closely with his father.

Iran’s constitution states that an elected body of clerics, called the Assembly of Experts, must pick the supreme leader. But the assembly is more of a ceremonial body with limited power, according to observers, and Khamenei is likely to have a major say in determining who takes on the mantle.

Raisi’s death has highlighted that Mojtaba is the only “obvious” candidate in line to succeed his father as supreme leader, Saleh said.

Iran’s economy has taken a hit under Raisi, with the country’s currency, the rial, reaching record lows, losing at least 55 per cent of its value in the last three years.

“One thing about Raisi was that he was not popular at all. He wasn’t able to deliver on his economic promises. We saw a further retraction of political space and a reduction of freedoms under his rule … he was not well-liked by Iranians,” Kamrava said.

Power struggle looms

The most pressing political issue for Iran at the moment is holding a vote to elect its next president, which is set to take place within 50 days. First Vice-President Mohammad Mokhber was appointed as acting president of the Islamic Republic on Monday, and is expected to organise the election.

Observers warns of a potential power struggle over the presidency, particularly among the country’s ultraconservatives. According to Saleh, hardliners could look to Raisi’s death as an opportunity to gain power and influence domestically.

Political analyst Arash Azizi said the regime’s focus would now be on “an orderly transition of presidency.”

“I expect a harsh struggle waged by various factions of the Islamic Republic over who gets to become president,” said Azizi, a writer and a senior lecturer of history and political science at Clemson University in the US.

“There won’t be a constitutional crisis as the Islamic Republic is rather good at an institutional response to moments like this … But there will surely be a power struggle over the presidency,” he said.

Observers say suspicions of foul play surrounding Raisi’s death could fuel conspiracy theories questioning the true nature of the accident. This was especially problematic “in a closed system like the Islamic Republic, where there is no free press”, Azizi said.

Continuity in foreign relations

Notably, there were fewer immediate reactions from leaders in the West, but the European Union and Japan did offer their condolences.

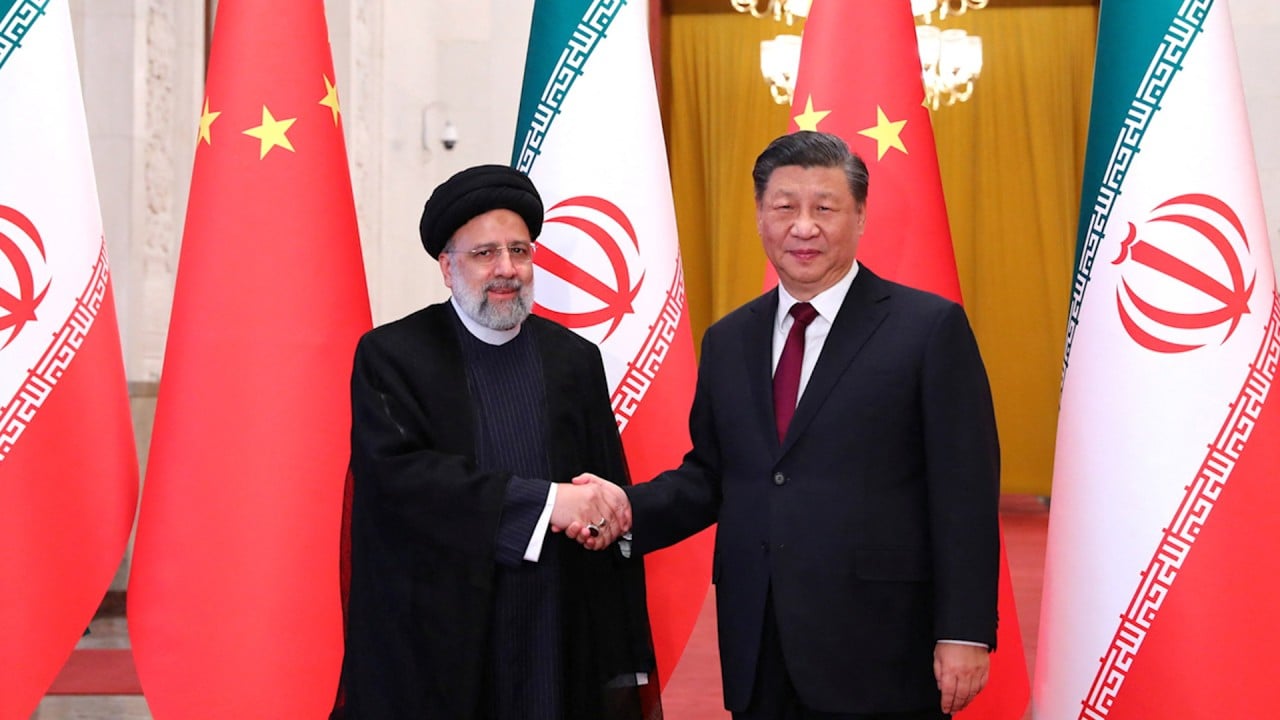

Raisi took on the presidency three years after the sanctions were put in place but had not been able to come to an agreement with the US. Instead, Iran shifted its approach from engaging with Western nations to fostering closer ties with Russia, China and India.

According to analysts, little is expected to change in terms of how Iran conducts its foreign relations.

“When it comes to key foreign policy issues and strategic decision-making, the president has very little say … the supreme leader and the deep state play a big role and are the ultimate decision-makers,” said Iranian studies specialist Saleh.

“The foreign minister, who also died along with the president … was able to draw Iran closer to countries like China, India and, most significantly, Russia,” said analyst Kamrava. “I don’t think we’ll see major changes to this in the foreseeable future.”

Kamrava added that it was evident from Supreme leader Khamenei’s response and statements to the people of Iran that the government’s focus was on continuing “business as usual”.

“Khamenei has said the country’s borders are safe, the country is safe, there will be political continuity as normal. I think that’s the government’s primary focus right now,” he said.

“We see that in the live state media television feed that was being broadcast even before the death was confirmed … it’s business as usual with all sorts of arrangements being made for what is next.”

Additional reporting by Reuters