The second follow-up, Infernal Affairs III, would be a sequel which followed directly on from the first film, and also backtracked in time to tie up some loose ends.

The film enjoyed massive success at the Hong Kong box office when it was released in 2002, and almost single-handedly set the city’s film industry back on track after the problems it faced arising from the popularity of Hollywood films in the city and the fallout from the 1998 Asian economic crisis.

Infernal Affairs benefited from being pegged to a strong theme, made implicit in the Chinese title, which translates roughly as “no way out” and refers to the Buddhist notion of Continuous Hell – a place where those who have committed the most heinous crimes on Earth end up.

The title is a metaphor for the hellish existence of the police and gangsters in the film.

It had particular relevance for Andy Lau’s triad spy, who betrayed his brothers in the gang, and his new-found colleagues in the police, to achieve his personal aims and then cover his tracks.

Infernal Affairs II, released in 2003, had no such philosophical concerns – it was an old-school triad drama about honour and betrayal. Although much less metaphysical in nature than the original, it worked very well on its own terms.

“The cast is excellent, and the filmmakers provide the players with plenty of opportunities to flex their thespian muscles,” the Post’s Paul Fonoroff wrote in his review. “Technically the production cannot be faulted.”

The prequel turned out to be difficult. The problem was that there was no suspense, because we already know what happens to the characters

When Andrew Lau, Mak and Chong made the original, its box office success was by no means guaranteed – in fact, it was regarded by many in the industry as a risky proposition, as police films were thought to be out of favour with audiences.

So the team did not plan for a sequel, and had no qualms about killing off one of the main characters – a creative decision that played a big part in the artistic success of the film. The ending seems definitive, and makes its point perfectly. So how to go forward with it?

A prequel seemed the logical choice, but there were some concerns about matching the quality of part one. “We had to do this well,” Andrew Lau told the Post’s Winnie Chung in 2003. “We could not make a cheap movie just to exploit the original.”

He and Chong reportedly had difficulty getting the story right. “The prequel turned out to be difficult. The problem was that there was no suspense, because we already know what happens to the characters at the end of the film,” he said.

Leung and Andy Lau did not appear in the film, as it revolved around their younger selves, played respectively by Shawn Yue Man-lok and Edison Chen Koon-hei.

The filmmakers compensated for their stars’ absence by developing some extremely strong characterisations, and they tried to give the screenplay the reach and breadth of a novel.

“Two new characters are the mafia boss impersonated by Frances Ng Chun-yu, who is quietly compelling in the way he combines the refinement of a well-educated CEO with the cunning and viciousness of a wily predator, and a senior police officer portrayed by Hu Jun,” Fonoroff wrote.

Ng was considered for a role in the first film but wasn’t available. His scheming triad boss in part two had him playing against type, as he had to appear calm and collected rather than wild and unpredictable.

“Francis is easily agitated,” Andrew Lau said in an interview, “but he decided to play a character who is never agitated. It was a challenge for him.”

Ng, for his part, said he could not find much of the triad boss Ngai within himself, and simply stuck to the script.

The story meanders, but does a reasonable job of providing a backstory to the original. Although the characters work together well enough in the film’s sprawling plot, their relationships only reflect those of the first, more sophisticated, movie in the most basic terms.

The original Infernal Affairs was a clever, Hong Kong-style police drama, but part two suffered from delusions of grandeur; it styled itself as a Hong Kong version of The Godfather, something more than hinted at by its resounding operatic score.

Part three arrived on screens just a few months after part two. But the story had run out of steam, and the result was messy. Andy Lau, whose character was still alive at the end of the original, returned, as did Tony Leung, whose character had been killed.

To accommodate Leung, the story had two timelines split by his character’s death – one details events six months before it, the other is set 10 months after it.

“We felt that the storyline could be developed further,” Mak told the Post. “How did the characters arrive at this stage? What were their connections to each other? These were questions that we thought the audience would be interested in.

“And the other question is, of course, does Ming [Lau’s character] get away with murder?”

Leung was intrigued by how the filmmakers would resurrect his character.

“Before they started working on the script, I really didn’t see how it could be done,” he told the Post. “So I was interested in finding out. They managed to find an interesting way of bringing me back through a series of flashbacks.”

The original saw Lau’s Ming doomed to exist in “continuous hell” because of his actions, living with his guilt, and always terrified that his true criminal nature will be discovered by his police colleagues.

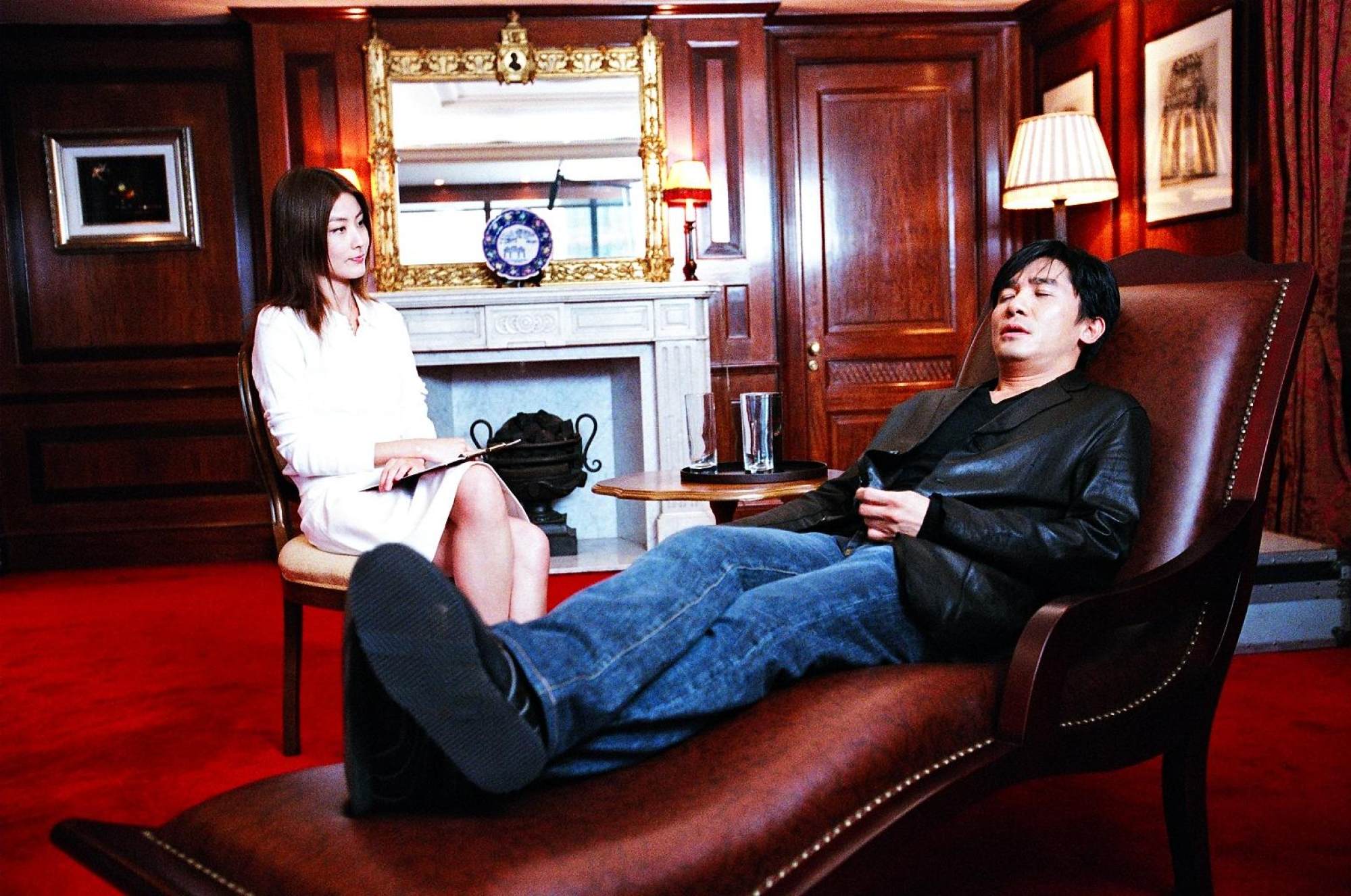

The third film has him suffering from mental illness and delusions, driven by his overwhelming guilt and uncertainty. Lau gives the part his all, but the film’s various ideas fail to add up.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.