One weaver, who declined to be named, said the visitors used derogatory words on him.

Several others from the community echoed similar concerns, but said it had caused no bad blood in the neighbourhood because the sari business thrived on interdependency, with Hindu traders supplying the raw materials and buying the garments from Muslim weavers.

“We have never heard of such a thing,” said Vidya Sagar Rai, the BJP’s Varanasi chief. “There may be some unwanted elements who may have tried to provoke people, but there has been no tensions in the city. The prime minister held a roadshow recently and people from all communities participated.”

Another BJP leader, who did not want to be named, claimed opposition parties instigated such incidents to give the ruling party a bad name during elections.

Silk saris from Varanasi are coveted all over India and the overseas diaspora because they are the outfit of choice for special occasions such as weddings.

People from the weaver community say the city’s infrastructure has improved under Modi – roads have been broadened, steps leading to the Ganges River for ritual baths have been spruced up and lighting installed in several places.

But many have expressed unhappiness over the tenor of speeches during the country’s ongoing national election, which have raked up issues relating to Muslims time and again.

“We want a good and clean administration, like everybody else. But it hurts us when we hear remarks about Muslims,” said Mohammed Faheen, a 26-year-old weaver whose family has lived in the city for generations.

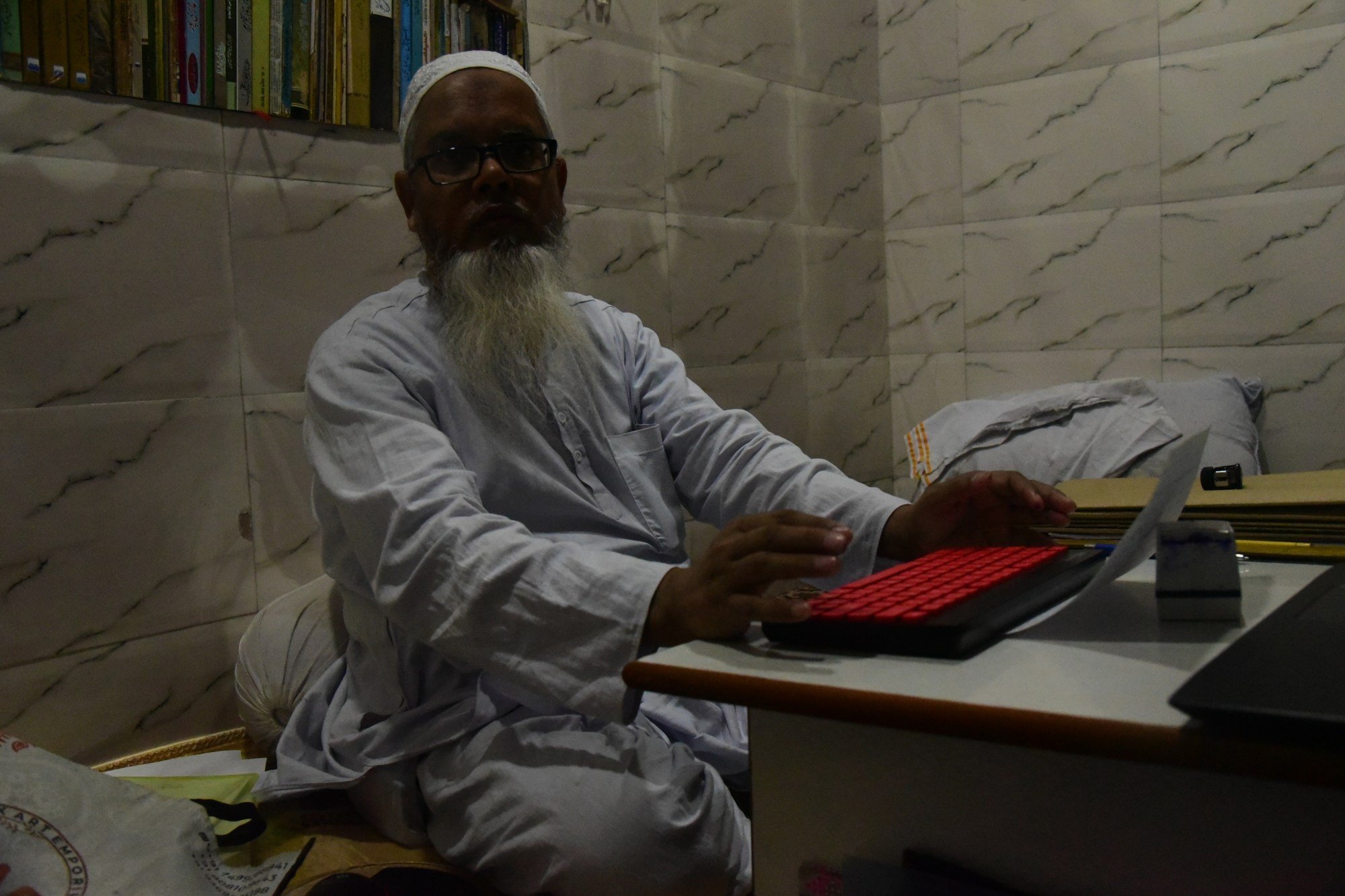

Abdul Wasim, a mufti or Islamic scholar who has the power to rule on various religious and personal matters, said he was dismayed by the comments on Muslims.

“It has been 10 years since they have been in power. Do they have nothing more relevant to talk about than raising Hindu-Muslim issues to get more votes?” he said. “People are upset, and they wonder in what direction the nation is heading.”

“But they have stopped paying attention to such talk because they realise it’s meaningless,” he added. “If they do, then it can cause tensions.”

Though the peace in Varanasi had largely been maintained by the two communities’ long-standing relationship, Wasim rued the fact that violence had occurred in other parts of the country.

“Whenever a person steps out of his home and the city, family members worry about their safety,” he said, adding that people had been attacked on trains.

In July last year, a railway police constable on a Mumbai-Jaipur train shot dead three Muslim passengers and his superior officer.

In another incident in New Delhi, a Muslim man was tied to an electricity pole and thrashed by people because he was suspected to have taken a banana meant to be a temple offering.

Wasim reiterated the complaint of weavers that some “outsiders have been trying to provoke anger” occasionally, but added that the strong understanding in the local community, especially in the sari business, had ensured peace was maintained.

According to Wasim, earning a living from the city’s sari business has become more difficult since the Covid-19 pandemic caused a drop in sales. Some families have even moved to other cities in search of employment.

The BJP’s Varanasi chief Rai disputed this claim, saying that business had been booming at many sari shops since the construction of the Kashi Vishwanath corridor encircling the city, which he said brought in a steady stream of domestic and foreign tourists.

The corridor, inaugurated by Modi in December 2021 and set to be expanded, connects the city’s ancient Kashi Vishwanath Temple and other important pilgrimage sites through a modern pathway to avoid the narrow and congested lanes that would hamper pilgrims earlier.

Varanasi’s lanes and alleyways have always commanded a steady flow of pilgrims. It is home to the Kashi Vishwanath Temple, dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, and also Sarnath, where Buddha is believed to have taught his first sermon.

It has more than 1,000 holy Muslim places, three Sikh Gurdwaras, temples for the Jain community as well as churches.

People from the majority Hindu community, who live or ply their trade near the homes of the Muslim weavers, expressed hope that peace and amity would remain intact.

“We need each other,” said Sonu, a taxi driver who goes by only one name.

“The day this relationship breaks down, the entire sari trade in the city will come to a halt.”