Minister for Home Affairs and Law K. Shanmugam later that month said the government would look into legislating against cancel culture.

“We should not allow a culture where people of religion are ostracised, attacked, for espousing their views or their disagreements with LGBTQ viewpoints. And vice versa,” he said.

A survey last month found that about two-thirds of 500 respondents thought transgender people face discrimination in Singapore society today.

The same Ipsos survey, of people aged 21 to 74, showed that 45 per cent of respondents supported LGBTQ people being open about their sexual orientation or gender identity, while 15 per cent did not.

On marriage equality, about half said same-sex couples should be allowed to marry legally or be allowed to obtain legal recognition, while a quarter of respondents disagreed.

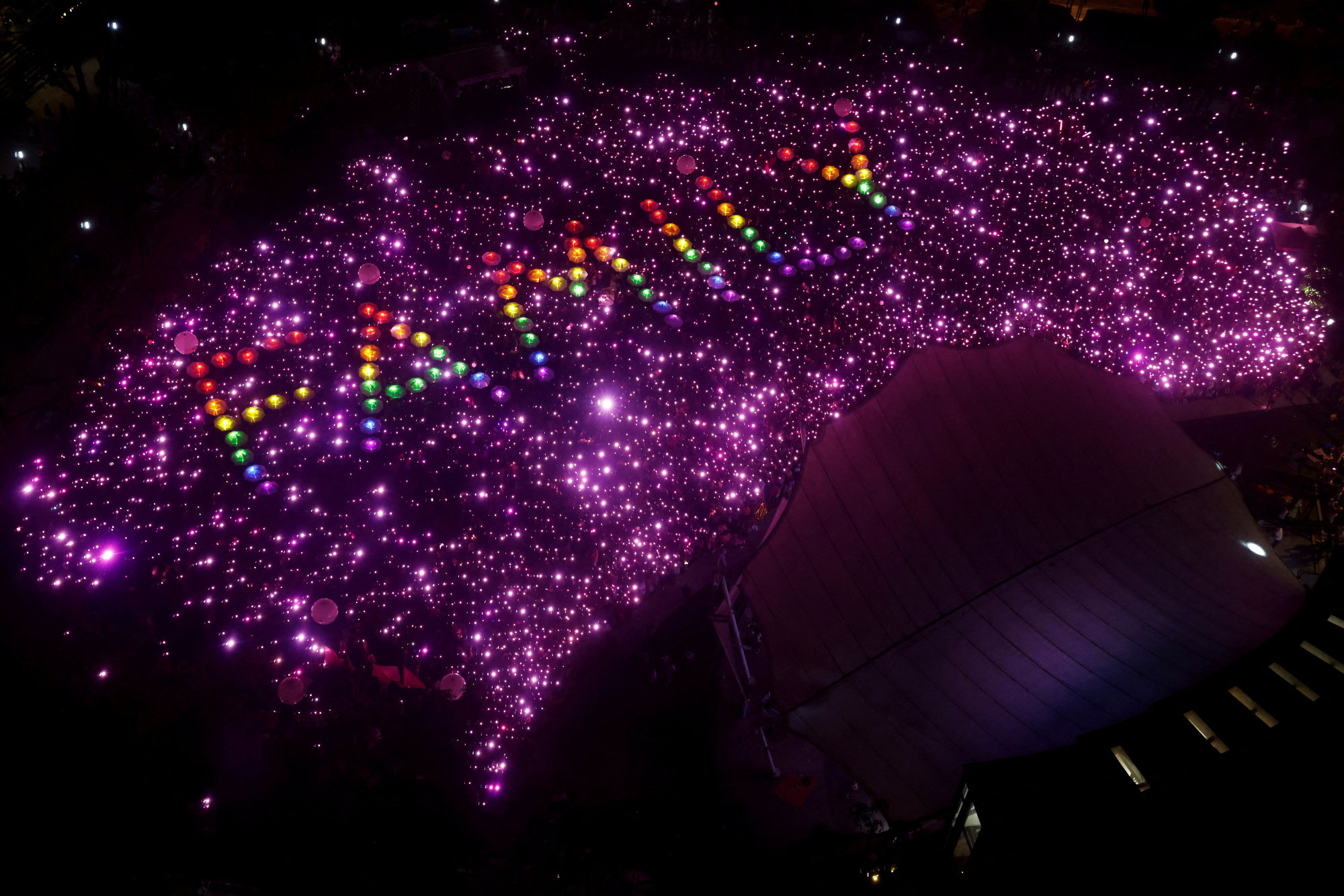

Organisers of Pink Dot, Singapore’s annual LGBTQ pride event, expressed disappointment about the cancellation of the talk, saying it could have helped to reduce stigma and encouraged a more informed and inclusive society.

They noted a trend of “certain quarters” successfully mobilising to shut down such events for going against the groups’ personal beliefs.

Protect Singapore said it welcomed discussions on gender dysphoria, but panels should include “organisations and individuals who provide scientific information on sex and gender”.

On Tuesday, it rejected the assertion that it “orchestrated a campaign” to cancel the panel, telling local news site The Online Citizen the move came from “ordinary people who simply had enough” of LGBTQ activism “and its negative impact on the field of science”.

Mathew Mathews, principal research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Institute of Policy Studies, said “greater expectations” existed for discourse in society now “particularly on how LGBTQ persons have been discriminated against”.

Mathews, who has studied Singaporeans’ attitudes towards LGBTQ people, said the focus of activists and advocates has shifted since the repeal of Section 377A.

“Since that has been achieved, more of those who are concerned about LGBTQ issues want more public education and understanding of the lives of LGBTQ persons,” he said.

He said those opposed to the repeal feared it would be a slippery slope, leading to stronger LGBTQ rights and greater challenges for those with more conservative beliefs.

“You can expect that more of them will be guarded to discourse on this issue, especially if it is conducted in or by public institutions, which they expect should adopt a neutral position on the matter,” Mathews said.

“The question is whether advocates for LGBTQ rights should have space to be able to influence Singaporeans about their positions on gender and sexuality.”

In a plural democratic space, advocates for LGBTQ rights and those who take conservative positions on gender and sexuality should both be allowed to influence Singaporeans, Mathews said.

Michelle Ho, an assistant professor of feminist and queer cultural studies at the National University of Singapore, cautioned against polarising the recent incident.

“Approaching this incident in the form of a divisive discourse, e.g. us versus them, is unhelpful because it potentially hurts religious LGBTQ individuals – particularly youths – who have intersecting identities,” Ho said.

“To avoid being caught in such a bind and to be able to see things from another’s perspective, I would recommend more dialogues with various people, especially if they tend to think quite differently from us.”

In October last year, Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University said it would review its internal processes after a drag performance was staged as part of celebrations for the 10th anniversary of its Centre for Contemporary Art.

“Given the sensitivities associated with the said performance, it should not have been staged as a public event,” the university said to local media at the time.

“As a higher education institution, the university maintains its policies and position to reflect widely accepted social norms and practices in Singapore.”