These refugees can acquire Indian citizenship within five years even if they enter the country without papers.

India’s Home Minister Amit Shah on March 11 announced details about the implementation of the CAA. Shah, a close Modi aide, said on X the CAA would “enable minorities persecuted on religious grounds in neighbouring countries to acquire Indian citizenship”.

Critics have slammed the delayed implementation of the law by four years, saying it was deliberately timed just before the election. On Saturday, India’s election authority said polls would begin in phases on April 19.

The 2019 demonstrations triggered a crackdown and led to the deaths of more than 100 people, mainly Muslims. Several Muslim scholars accused of inciting violence at the protests were also arrested and jailed.

Is India targeting Muslims with committee to address population growth?

Is India targeting Muslims with committee to address population growth?

The law’s implementation on March 11, just weeks before Modi seeks an unprecedented third term in the election, has reignited fears of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) alleged anti-Muslim bias.

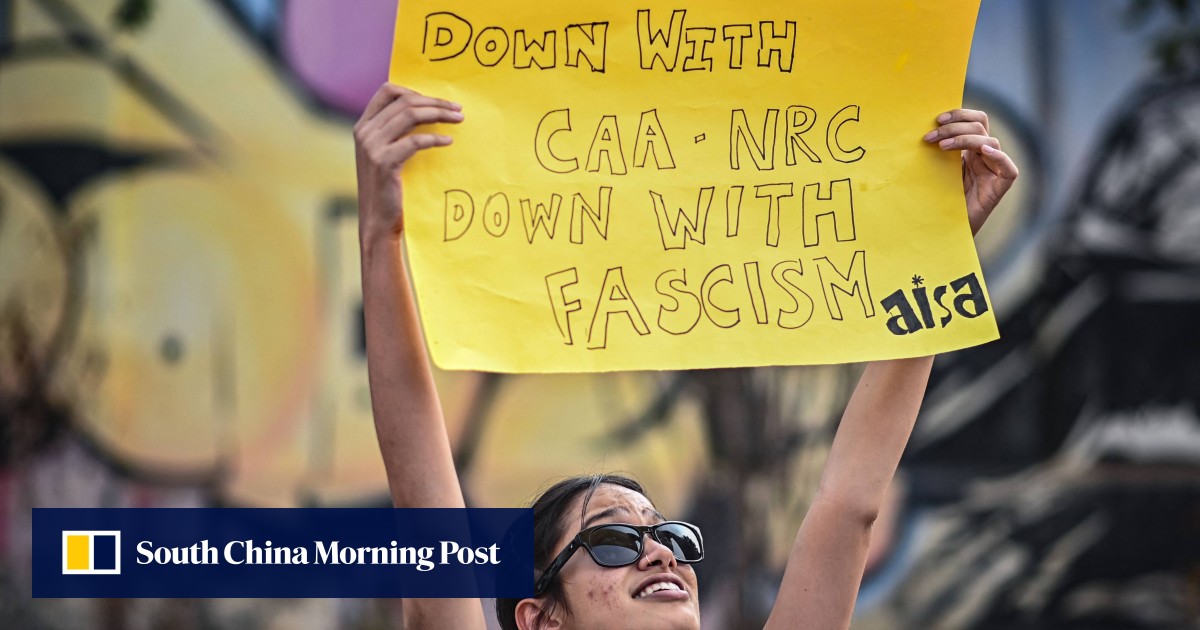

Protests erupted across India, including in Delhi, following Shah’s announcement. Government forces were deployed in recent days to quell the unrest in Muslim-majority areas in the capital. Activists from various organisations staged demonstrations, burning copies of the law.

Legal experts say the rules would make India a sanctuary for Hindus and marginalise its 200-million Muslim minority. Before the CAA, an applicant’s faith was not specified by the authorities and a foreigner could be eligible for Indian citizenship after 11 years of residence.

Critics noted that the CAA ignores persecuted Muslim individuals overseas such as Hazara Muslims in Afghanistan, Ahmadis in Pakistan or Rohingyas in Myanmar, many of whom have been detained in India after fleeing their countries. Amnesty India said in a post on X on March 14 that the CAA violates constitutional principles of equality.

Since assuming power in 2014, the BJP has faced criticisms for fostering a hostile climate against Muslims in India. Over the past decade, many Muslim Indians have accused authorities of human rights abuses ranging from property demolitions to attacks on religious sites.

Political analysts and rights advocates say the government has prioritised electoral gains over addressing the country’s economic challenges.

Lawyer Aman Wadud said the CAA was discriminatory against Muslims, and dismissed claims by Delhi that the new law gave refuge to religiously persecuted communities.

“Any illegal immigrants from six non-Muslim communities can seek citizenship, regardless of persecution. The talk of religious persecution is mere political rhetoric,” Aman told This Week in Asia.

“Look at statements from BJP leaders like the Assam Chief Minister calling all Muslims ‘Bangladeshis’. They are persecuting Muslims here through such laws and rhetoric that paints them as outsiders.”

A Delhi-based research fellow, who wished to remain anonymous, said the CAA and the National Register of Citizens (NRC) were part of the same divisive agenda by Modi’s BJP government.

The researcher said the NRC aimed to identify “undocumented immigrants” – a group the government had anticipated would be predominantly Muslim – by demanding documentation that many could not produce due to loss or damage over the years.

However, in Assam, when the NRC rules were implemented, most on the undocumented list were non-Muslims.

“The CAA cannot be seen in isolation. It’s one arm of the pincer while the other is the NRC. By launching them separately, the BJP tries to portray them as distinct but they are two arms of the same political endeavour.”

Safoora Zargar, a Muslim student activist, said the move to implement the CAA ahead of the 2024 elections was a sign of Delhi’s weakness and urged activists to continue defending Indian democracy.

“The government has to resort to such overt vulgar displays of power to give reason to its voter base to vote for them again despite all the failures,” she told This Week in Asia.

The CAA has also drawn international criticisms since it was mooted.

The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights expressed concerns earlier this week over the law’s discriminatory nature, saying India might have breached its international human rights obligations.

US State Department spokesman Matthew Miller earlier this week emphasised the importance of religious freedom and equal treatment under the law for all communities in India, saying Washington was monitoring the situation closely to gauge the impact of the CAA.

However, India’s Ministry of External Affairs spokesman Randhir Jaiswal on Saturday said the CAA was “an internal matter of India, aligned with our inclusive traditions and our enduring commitment to human rights”. The US and UN reactions were “misplaced, misinformed and unwarranted”, he added.

Neighbouring Pakistan has lambasted the law as discriminatory, with its foreign office spokesman Mumtaz Zahra Baloch on Friday calling India a “Hindu fascist state”.

Dr Zafarul-Islam Khan, a former chairman of the Delhi Minorities Commission, said the implementation of the CAA was to “exploit” communal divisions for electoral gains and further undermined the status of Indian Muslims.

He warned, “More steps will follow until Indian Muslims are finally turned into second-class citizens.”