Posters of Prabowo and Widodo – since taken down during the quiet phase – could be seen plastered all over key provinces, all but signalling the president’s endorsement. Widodo, or Jokowi, as he is widely known, belongs to the ruling Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P).

Indonesia election: is Jokowi’s ‘partiality’ for Prabowo a double-edged sword?

Indonesia election: is Jokowi’s ‘partiality’ for Prabowo a double-edged sword?

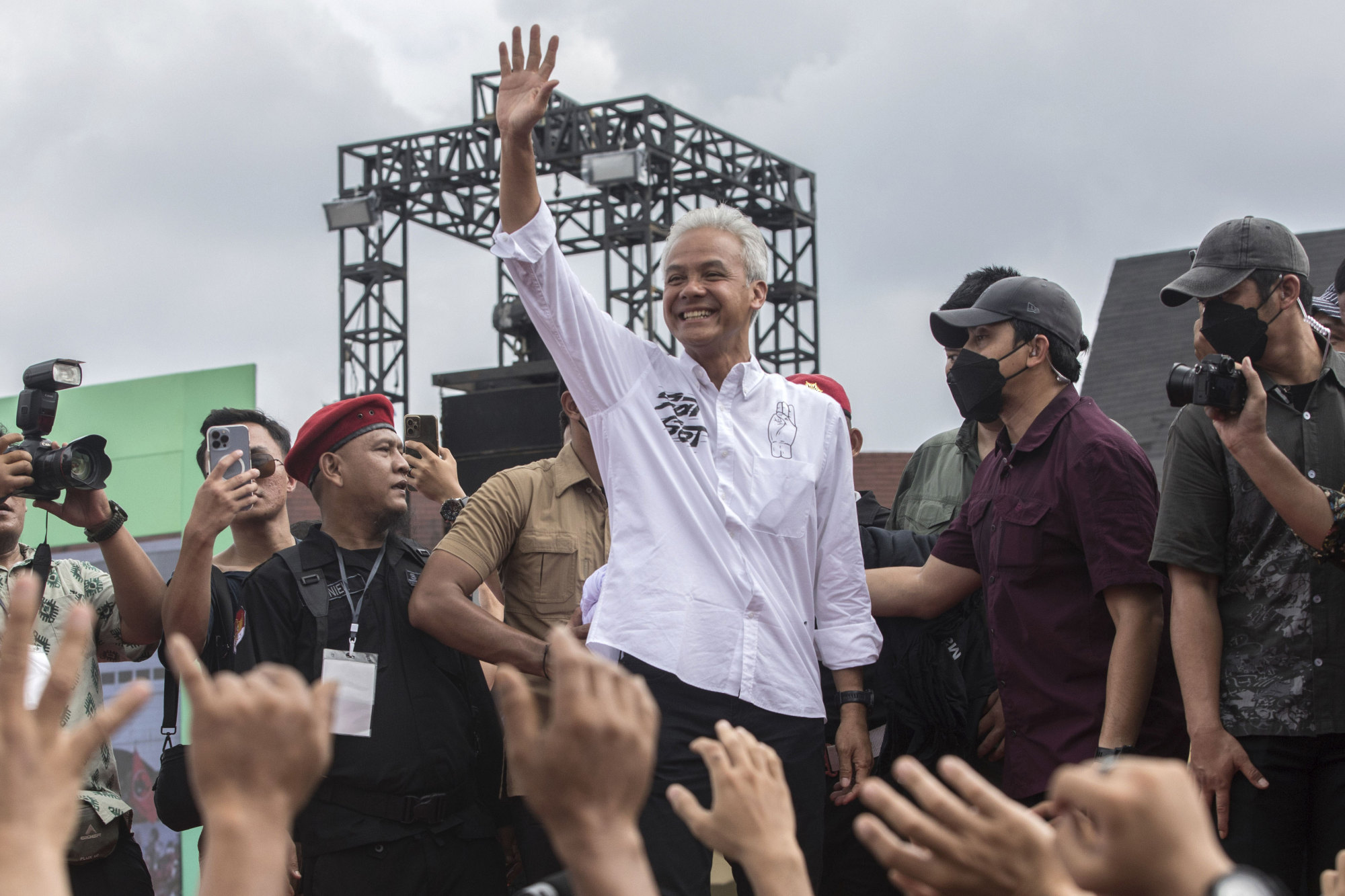

The PDI-P is fielding its own candidates, Ganjar Pranowo and Mahfud, who have not received even a nod of support from Jokowi and have become more critical of some of his policies. Ganjar has also declared he can win without the popular president’s support.

Yet all three pairs of candidates are viewed largely as centrists and in an election where the main issues have been on the cost of living and youth employment, few areas of ideological differences have emerged. Rather, the focus has been on the power of personalities.

On paper, at least two surveys show Prabowo and Gibran as front runners, surpassing the 50 per cent of the vote needed to emerge as winners on Wednesday. If no one receives this share, the top two candidates will face off in a second round of voting on June 26.

The results released by pollster Indikator on February 9 showed Prabowo ahead at 51.8 per cent of the votes, while rivals Anies received 24.1 per cent and Ganjar obtained 19.6 per cent. The margin of error was 2.9 per cent.

Can Indonesia’s Ganjar force a run-off as bid for ‘total victory’ dries up?

Can Indonesia’s Ganjar force a run-off as bid for ‘total victory’ dries up?

Another survey by Lembaga Survei Indonesia showed Prabowo at 51.9 per cent, with Anies at 23.3 per cent and Ganjar at 20.3 per cent. The margin of error was also 2.9 per cent.

Much will depend on voter turnout, analysts have said. The country regularly enjoys about 80 per cent turnout and election day is a public holiday.

How effectively the candidates and their party machinery can mobilise voters on polling day will be critical, with Ganjar’s PDI-P seen as having an advantage given its formidable party machinery in critical provinces like Central and West Java. PDI-P also holds the largest number of seats currently in the legislature, underscoring its large voter base.

Seeds of discontent

But hitching his campaign to Jokowi, who enjoying popularity ratings above 70 per cent, has not been risk-free.

The president has faced accusations of bias and even though he has not officially endorsed anyone, Jokowi is seen as clearly siding with his son and Prabowo.

Since the controversial ruling that allowed Jokowi’s son to run, his brother-in-law has been demoted from his position as chief justice of the Constitutional Court. Both the court and the General Elections Commission, or KPU, have been found guilty of ethical violations.

A lot of these student movements do not want to see Prabowo win

The scandal sowed the seeds of a new movement that has taken hold and cannot be ignored: a steadily growing chorus of student and intellectual groups calling for democracy to be upheld amid mounting accusations of nepotism and weakened institutions.

“We have a growing student movement in dozens of Indonesian universities over the past week or so. How are they going to respond? A lot of these student movements do not want to see Prabowo win,” said Alexander R. Arifianto, a senior fellow with the Indonesia programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

Prabowo and Gibran have been quick to claim the youth vote as theirs, going by attendance at their rallies. Some 52 per cent of registered voters this year are aged below 40, with one-third of them younger than 30.

Whether the burgeoning student movement in opposition to Prabowo will translate into an actual force to be reckoned with remains to be seen.

‘Not fair, not free’: students slam Jokowi’s lack of neutrality in election

‘Not fair, not free’: students slam Jokowi’s lack of neutrality in election

But Jokowi has not helped matters by declaring that the president is legally allowed to campaign and take sides during an election. After the outburst of defiance was greeted with opprobrium, especially from intellectuals and academics, he dialled down the rhetoric.

Sana Jaffrey, a research fellow at Australian National University specialising in Indonesian politics, said there was a “mobilisation by Indonesian intellectuals, academics at great personal cost” to criticise the president and call for neutrality.

“And there was sort of great momentum to this and so he’s rolled it back saying it is allowed but I’m not going to do it. My sense is that it might have backfired and might have given a boost to people who are thinking of supporting other candidates,” she said.

First-time voter and university student Giantri Siti Safitri, 18, is among them. She has decided to vote for Anies because of the improvements he brought to her hometown Jakarta as its governor and not for Prabowo “because there are ethical issues”.

“A lot of young people get their news and information from TikTok, and Prabowo is very popular there. But if you read a bit deeper, you can find out all the issues from his past,” she added, referring to his troubled time as a military chief, especially during the 1998 riots sparked by the Asian financial crisis.

Prabowo and the Jokowi question

A senior member of the Indonesian elite who has chaired state-owned enterprises and listed companies said one aspect of the campaign that appeared to be different from previous elections was the relative absence of a consumption spike. To him, this indicated that the election had been clean so far and represented a maturing of Indonesia’s democracy. “Not as much money appears to be floating around,” he said, on condition of anonymity.

But another member of the vast establishment said he would not be too quick to conclude it would remain this way. “There is a tradition of ‘serang fajar’, where supporters have been known to give incentives, shall we say, to get voters to side with them and this is done in the morning or at dawn.” Serang fajar translates as ‘dawn attack’.

Reconciliation has been a recurrent theme in Indonesian politics over the decades with Prabowo himself, a presidential candidate who lost out to Jokowi in 2014 and 2019, becoming inducted into his cabinet as defence minister.

If Prabowo does manage to win on February 14, the question is whether he will co-opt erstwhile rivals into any government post, not an unusual arrangement going by past precedents. More intriguingly, attention will be paid to just how Prabowo will live up to whatever pact he and Jokowi had made to ensure policy continuity and keeping his legacy.

The most obvious point of influence will be via his son, Gibran. “But the Indonesian constitution does not give any equal power to the vice-president. So what falls under his purview is really sort of up to the president. He can be parked somewhere in an unimportant position,” researcher Jaffrey said.

“Prabowo did not contest the presidency for three tries so that you do somebody else’s bidding,” she added.

Dedi Dinarto, lead Indonesia analyst at public policy advisory firm Global Counsel, said: “The post-election dynamics between Prabowo and Jokowi represent a different challenge altogether, with potential frictions arising due to the high level of pragmatism in Indonesian politics.”

Jokowi under renewed fire for saying presidents ‘can take sides’ in election

Jokowi under renewed fire for saying presidents ‘can take sides’ in election

But even if Prabowo fails to claim outright victory on Wednesday, the consensus seems that it is his to lose. Can he hang onto his lead?

Anies appears to be slightly ahead of Ganjar in the surveys and is likely to be a formidable opponent, analysts say.

An articulate university professor who obtained his doctorate from the United States, Baswedan was once an education minister in Jokowi’s first cabinet in 2014, but he lasted less than two years on the job before going after the Jakarta governorship.

Interviews by this Week in Asia over the past week found that the elite establishment appeared to be split between rooting for Prabowo given his front runner status and sticking with PDI-P and therefore Ganjar.

However, analysts and elite observers were quick to also point out that all three presidential candidates are centrist, even though Anies is associated with the more conservative elements of Indonesian society. And despite both he and Ganjar pushing for a vision of change, analysts believe all three favour developmental policies and are unlikely to depart dramatically from Jokowi’s incrementalist approach.

Indonesia’s next president will uphold Jokowi’s legacy. But will that be enough?

Indonesia’s next president will uphold Jokowi’s legacy. But will that be enough?

“Realistically, none of the candidates are likely to diverge significantly from the policies of the Jokowi administration,” Dedi said.

All three candidates are unlikely to compromise on Indonesia’s non-aligned foreign policy principles. “The country will continue leveraging its non-alignment stance to engage with all nations, provided there are political and economic benefits to be gained,” Dedi added.

But for voters like David, 50, these are distant concerns. A street cart food seller in Jakarta’s Cikini area, he spoke for many backing Prabowo when he cited the minister’s amiable personality.

“I like the guy,” he said. “That’s all it is. I like him more than the other candidates, and he has been trying to become president for some time, so this is his time.”