Indonesia had been poised to become a major semiconductor component manufacturer, but investors shifted their focus to Malaysia instead because of Jakarta’s regulations, Airlangga claimed without providing further details. As a consequence, he said Indonesia must now work towards regaining the semiconductor investments it had “lost”.

One country that Indonesia could target to grow its semiconductor industry is China, which has expressed interest in producing chip components in the proposed Beijing-backed economic zone on Indonesia’s Rempang island, near Batam.

The proposed deal has sparked outrage among civil society and non-governmental groups, as thousands of the island’s residents are expected to be displaced to make way for the project.

In April, the Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs said it would intensify efforts to develop the semiconductor industry as a key growth driver in line with Indonesia’s vision to become an advanced economy by 2045 on the 100th anniversary of its independence.

Too little, too late?

The fiercest competition to woo semiconductor giants is expected to come from Indonesia’s two immediate neighbours.

“I offer our nation as the most neutral and non-aligned location for semiconductor production, to help build a more secure and resilient global semiconductor supply chain,” Anwar said, adding that Malaysia aimed to secure at least 500 billion ringgit (US$106 billion) in fresh semiconductor investments under a new National Semiconductor Strategy.

Malaysia’s semiconductor industry contributes significantly to its economy, accounting for about 25 per cent of its gross domestic product. Its assembly, packaging and testing operations supply 13 per cent of global demand.

Singapore’s semiconductor output accounts for about 11 per cent of the global market.

Global semiconductor companies like GlobalFoundries from the US, Siltronic from Germany and United Microelectronics Corporation from Taiwan have invested billions of dollars in Singapore in recent years.

Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat said earlier this month that the semiconductor industry accounted for almost a quarter of the country’s value-added manufacturing activities, while manufacturing as a whole makes up 20 per cent of Singapore’s economy.

Ronald Tundang, a researcher at the Chinese University of Hong Kong focusing on international economic law, said Airlangga’s claims about Malaysia and Singapore supposedly sabotaging Indonesia’s semiconductor development “reflect geopolitical tensions and competitive pressures within the region”.

“However, without substantial evidence, these claims could also be viewed as political rhetoric intended to galvanise support for domestic initiatives,” he said.

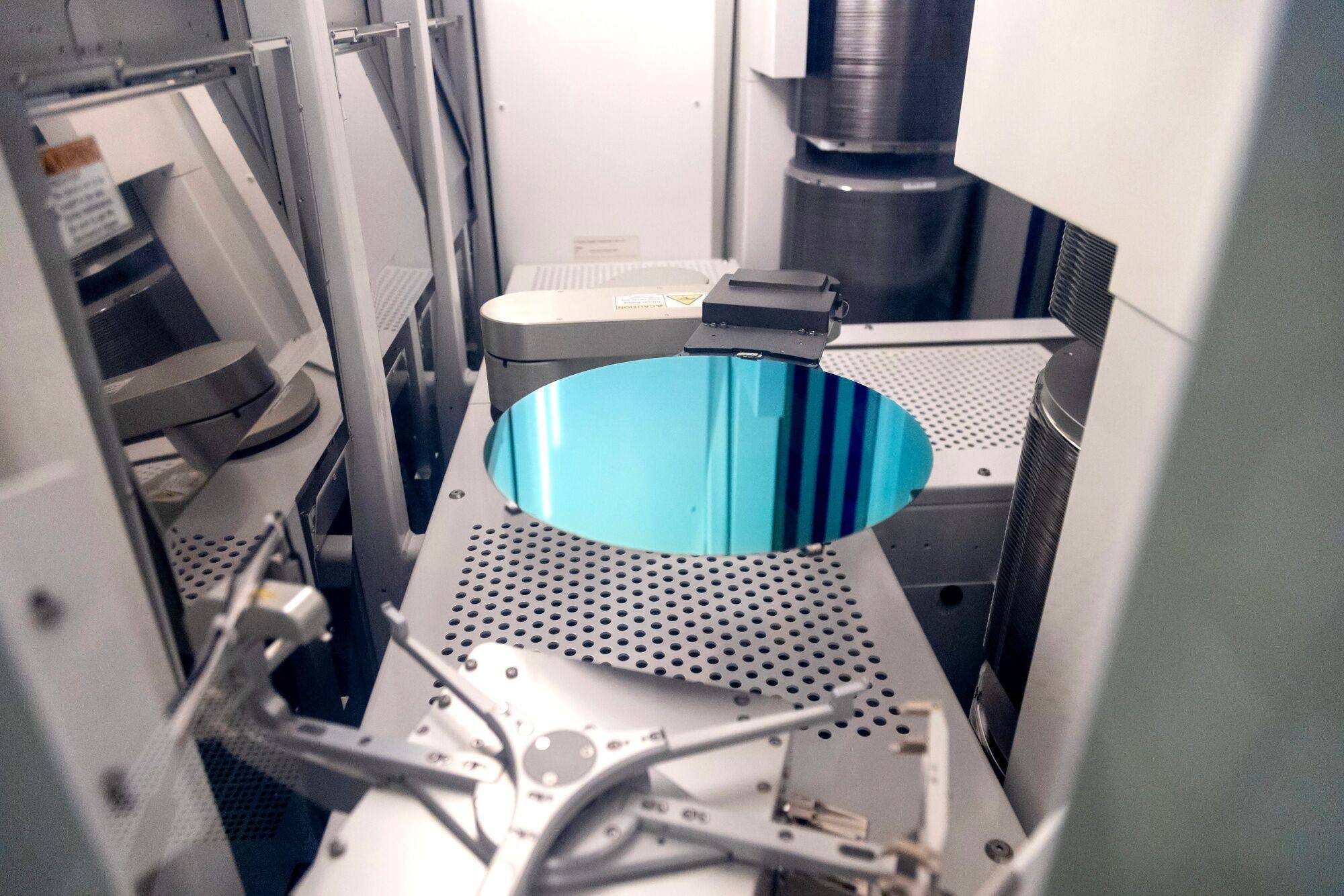

In September, Indonesia announced that it had begun working on a road map to develop its silica industry to kick-start its semiconductor manufacturing strategy. Silica is a key raw material required to make silicon wafers, an important building block of semiconductors.

But analysts say these efforts might be too little, too late.

Kyunghoon Kim, an associate research fellow focusing on industrial policies at the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, said Indonesia did not appear to have a “coherent strategy” to develop its semiconductor industry.

“Without the experience of producing semiconductors, Indonesia will have to inject fiscal resources to attract investment,” he said.

This could prove challenging given Indonesia’s financially conservative policies, which it has maintained since the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Kim added.

Observers note that while Indonesia has significant silica resources, this may not give it a competitive advantage as silica is widely available globally and other regional countries have more established semiconductor manufacturing facilities.

Major US semiconductor makers like Intel, Micron and Texas Instruments, and Dutch chip equipment maker ASML were already in Southeast Asia but their regional efforts have excluded Indonesia for many years, Kim said.

“In terms of back-end operations, their efficiency is already very high in Malaysia and Singapore so it will be very difficult for Indonesia to compete,” he said.

As the US looks to move semiconductor production away from China, Vietnam has emerged as a formidable competitor to Indonesia, being the third-largest US semiconductor partner in Asia, following South Korea and Taiwan.

“Malaysia is better in human resources and Vietnam’s trade policy regime is more facilitating and connected with the world’s major trading partners so it’s very suitable for a highly complex global value chain,” said Dandy Rafitrandi, an economics researcher at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies policy think tank in Jakarta

Regulatory challenges

Despite Indonesia’s ambitions to grow its semiconductor capabilities, it has struggled to attract significant new investments or expansion plans from major global chip manufacturers. One exception is German firm Infineon Technologies, which announced in 2022 it would expand its back-end manufacturing operations at its existing facility in Batam.

To become more competitive in the semiconductor industry, analysts say Indonesia must invest in research and development while also developing a skilled workforce capable of supporting advanced manufacturing activities.

The Centre for Strategic and International Studies’ Dandy warned that Indonesia’s inflexible business regulatory environment could hamper its aim to move up the semiconductor value chain.

“We have quite a restricted trade policy in Indonesia with local content requirements, import restrictions and inconsistent regulations,” he said.

Legal expert Ronald agreed, saying regulatory uncertainty would deter foreign semiconductor companies from considering Indonesia for their regional expansion plans.

“Political instability and governance issues have historically skewed Indonesia’s economy towards natural resource exports and low-value manufacturing, limiting the workforce’s capacity in advanced technology sectors ,” Ronald said.

“Indonesia must address bureaucratic inefficiencies, policy inconsistencies, and corruption to effectively implement its industrial policies and attract high-value investments.”