Conrad – who died a century ago this summer – is best remembered as the author of Heart of Darkness (1899), the Congo-set novella that became the basis for the movie Apocalypse Now. Yet half of everything he wrote is set in the equatorial regions of Asia, including several novels inspired by this very river.

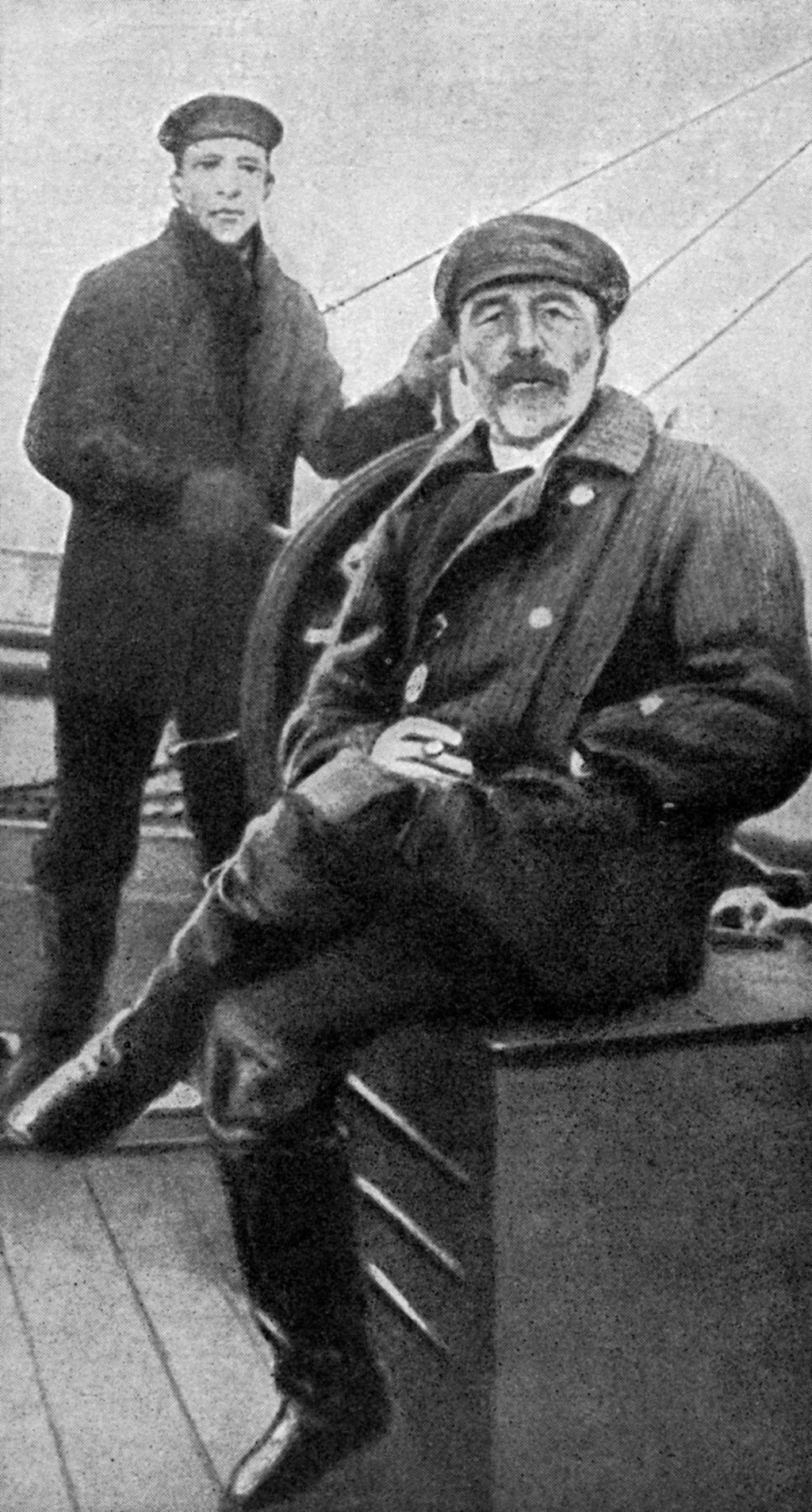

Before he was Conrad the writer, he was Konrad the sailor, a merchant seaman, not yet 30, who spoke English, his third language, with a thick accent. (Born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, he grew up in northern Ukraine as a subject of the Russian tsar.)

He would undertake this journey on four separate occasions in 1887 and 1888 as first mate of the SS Vidar – a trip that, from Singapore, took several months there and back. After 10 hours on this noisy, juddering work boat, in blazing sunlight and intense heat, I have a new-found respect for men of this profession.

The estuary begins to narrow as we approach Lingard’s Crossing, as it is called on old navigation maps. The passage was first charted by a British merchant adventurer, William Lingard, in the mid-19th century.

Lingard was the first European to trade on the Berau River, mostly in rattan, gum resin and gutta-percha, a natural latex derived from sap.

Conrad never met Lingard, yet he was sufficiently familiar with his legend – the Malays called him Rajah Laut, “King of the Sea” – that he would make the Briton the overarching figure in a trilogy of novels. In Conrad’s telling, William Lingard becomes Tom Lingard, captain of The Flash, the fastest brig in the East and the man who would claim this river as his own.

Because of strong currents Widarto, the captain of our boat – a chain-smoker and man of few words – is forced to dock. It is after midnight when we set off again, some 18 hours since our voyage began.

As we round a bend in the river, I make out lights twinkling against the silhouette of low-slung hills, and the town of Berau drifts into view, as it had for Conrad long ago, and with equal slowness.

Officially known as Tanjung Redeb – and called Sambir in the novels – the town is on a promontory where the Segai and Kelai rivers come together to form the Berau River. It was a small trading post in Conrad’s day but now serves as the capital of the Berau Regency, in Indonesia’s East Kalimantan province.

Home to 70,000 mostly Malay, Javanese and Bugis people, it is best known for its open-pit coal-mining industry, which produces 35 million tonnes of coal a year. As I amble along the Segai waterfront that afternoon, huge barges shift pyramids of coal downriver to be exported overseas, mainly to China.

The town’s other main product, to judge by the sound of recorded swallow calls blasted from rooftops, are birds’ nests – something else the Chinese cannot go without.

It was while unloading cargo at this riverside that Conrad first met Charles Olmeijer (1828-1900), a Dutchman and William Lingard’s trading representative in Berau. Conrad would later write about this encounter in a memoir, describing Olmeijer as “clad … in flapping pyjamas of crettone pattern … and a thin cotton singlet”.

“His black hair,” wrote Conrad, “looked as if it had not been cut for a very long time.”

Unimpressive as Olmeijer may have appeared, Conrad would make him the protagonist of his first novel, Almayer’s Folly (1895), written while the author was still at sea, and published when he was 38.

“If I had not got to know Almayer [Olmeijer] pretty well,” Conrad would write in a memoir, “it is almost certain there would never have been a line of mine in print.”

Somewhere along this riverside, among the stores selling fishing tackle and motorboat engines, Olmeijer had his home, and the area is where the fictional Almayer nurtured dreams of finding gold to escape his poverty.

Here, too, was the warehouse of the fictional Lingard & Co, already disintegrating as the novel begins, after another of Tom Lingard’s agents, Peter Willems – the focus of a prequel novel, An Outcast of the Islands – betrays his employer and ruins his business by revealing the secret passage up the river. (The third novel of the trilogy, The Rescue, concerns Tom Lingard’s backstory before his arrival in Sambir).

I spot a few ramshackle wooden structures, but none dating back, I think, to Conrad’s time.

I have better luck in the opposite direction, passing workmen unloading sacks of rice with a quayside clamour that would have been familiar to Conrad.

Further along, past the food carts selling bakso (meatballs) and mie ayam (noodles with diced chicken), I come upon several Bugis schooners. Although equipped with engines, their rigging and wooden hulls make them appear as if they belong in the age of sail.

During his visits to Berau, Conrad would have crossed paths with another of Lingard’s business representatives, his nephew. A tall and youthful Englishman, Jim Lingard would be the first European to permanently settle on the river (Olmeijer, a Eurasian, was born in the city of Surabaya in Java).

Given the honorific of tuan (lord) by the Malays, he would serve as the prototype for Conrad’s most sympathetic creation, the eponymous hero of the English classic Lord Jim (1900).

Lord Jim is the tale of a British seaman with “blue boyish eyes” and “capable shoulders” who, in a moment of weakness, abandons his ship after it hits a reef.

Stripped of his sailing papers and spurned by his peers, Jim eventually finds redemption as the talismanic protector of Sulawesi settlers in the fictional remote trading post of Patusan, one of the “lost, forgotten, unknown places on earth”.

These days, Berau does not feel so forgotten, with an airport and a road connection to Indonesia’s new capital, Nusantara, once it is built.

On the opposite bank of the Segai River is the village of Gunung Tabor, which feels closer to the spirit of Patusan. With its tin-roofed wooden houses flanking the river, and the local sultan’s yellow palace, or keraton, it has the air of a mini-fiefdom over which Jim might once have ruled.

In the novel, Patusan is divided into two seats of power: that of the corrupt Rajah Allang, and that of Doramin, the Bugis headman, Jim’s ally. In Conrad’s time, Berau functioned as a split sultanate: following a power struggle in 1810, one branch of the royal family ruled from Gunung Tabor and the other from across the Kelai River, in the town of Sambuliang.

The same split exists today, but the role of sultan is now purely ceremonial, for Indonesia has been a republic since 1950.

At the Gunung Tabor palace, among the display cases of Qing vases and ornate krises (daggers), are a pair of bronze cannons. I’m reminded of the “rusty seven-pounders” Jim used to chase out the chief’s enemies, thus winning the confidence of the people of the river, and earning the distinction of tuan.

Over at the Sambuliang palace, or at a building like it, the Rajah of Sambir, along with the despised Willems, conspired to force Tom Lingard out of business. It would be a Singapore-based Arab trader, with his line of steamers, that would supplant Tom Lingard on the river.

As in fiction, so in life: Conrad’s employer was also an Arab businessman based in Singapore. (His descendants, the Al Jufrie clan, still operate in Berau.)

Having lost its monopoly, Lingard & Co went bust. Tom Lingard, his beloved brig lost at sea, would squander the last of the company profits searching for gold upriver.

Almayer, his dreams of a wealthy retirement dashed, would succumb to opium. Young Jim, meanwhile, having salvaged his pride, would also come to a sticky end, betrayed once more by his wavering resolve.

Their real-life counterparts would go on to live more contented lives, and would now be forgotten had it not been for Conrad’s fateful arrival at this remote trading post.

Aside from the two palaces, there is little else to see, whether as a tourist or a literary pilgrim, and I spend the remainder of my afternoon strolling along the Segai waterfront.

The esplanade is busy with young people drinking coffee or juice, the golden light filled with mosque calls and swallow cries.

The Bugis schooners are still docked and the giant coal barges continue down the muddy, glistening river. Between them, perhaps, is the ghost of the Vidar, Conrad’s boat, leaving with rattan and resin, and enough material to fill several novels.