The “murky ecosystem” of vendors, brokers and resellers with “complex ownership structures” has also made it hard for public procurement oversight, Amnesty said.

“If Indonesia really is a democracy they should have an oversight mechanism … on the procurement [of the surveillance tools] and their implementation,” said Andreas Harsono, an Indonesian researcher with Human Rights Watch.

Nenden Sekar Arum, executive director at Jakarta-based SAFENet that advocates freedom of speech in Indonesia, said the public “has the right to this information, as the tools were bought using state funds”.

Amnesty International worked with several news outlets on the investigation, including Israeli newspaper Haaretz and Indonesia’s local news site Tempo.

Indonesian police spokesman Brigadier General Tjahjono Saputro declined requests by Tempo to comment on the purchase of the spy software.

Spokesmen from the national police and Indonesia’s intelligence agency did not immediately respond to This Week in Asia’s requests for comment.

‘Nothing new’

Andreas said news of Indonesian state agencies purchasing surveillance tools from Israel was “nothing new”, as Indonesia has had trade and military collaboration with Israel since the era of Indonesia’s former leader Suharto, despite a lack of official diplomatic ties between the two countries.

In recent years, multiple news outlets have shed light on the scope of Indonesia’s informal ties with Israel, including Indonesia’s procurement of surveillance software.

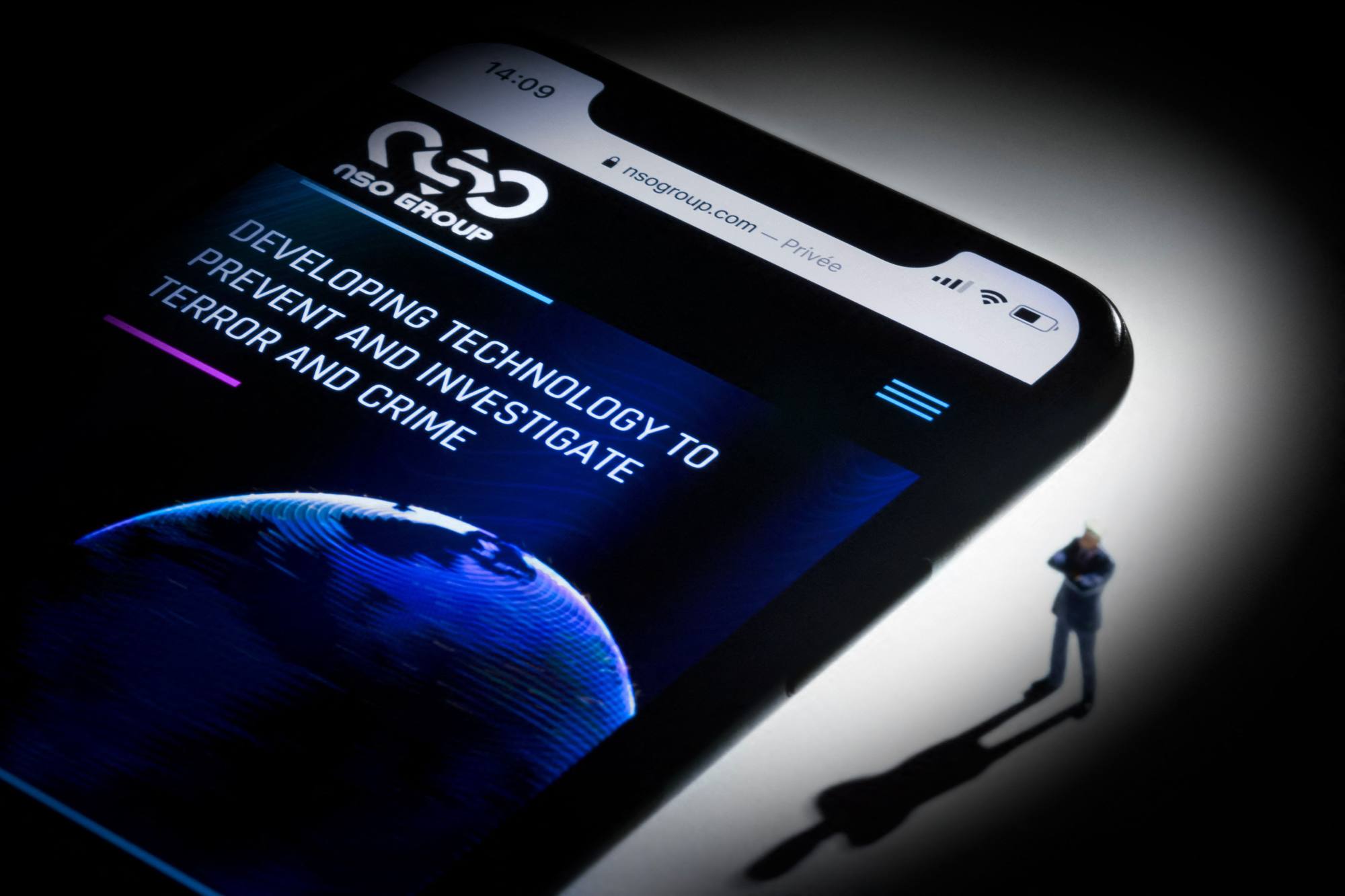

A report published in June last year by Indonesian whistle-blower platform IndonesiaLeaks found that NSO Group supplied Pegasus to the Indonesian national police and the State Intelligence Agency. The National Police denied the accusation at that time, while the agency did not respond.

In October 2022, Reuters said Indonesian government and military officials were targeted in 2021 with ForcedEntry, a spyware used by NSO Group to help foreign spy agencies take control of iPhones remotely.

Indonesian intel agencies were also keen on using spyware to monitor targets’ location, the report said.

The Indonesian police bought nine tracking devices that were delivered to the police’s logistics complex in East Jakarta in 2019 and 2020, according to the report.

Swiss-based tech company Polus Tech was the manufacturer of the devices, and Polus’ CEO, Niv Karmi, was one of NSO Group’s three founders.

The devices “help law enforcement to catch someone. But it doesn’t infiltrate mobile phones,” Karmi said in this week’s edition of Indonesia’s Tempo magazine.

Who’s the target?

Amnesty did not name individuals or organisations targeted by the surveillance tools in its report, but said malicious spyware was found in “domains that mimic” the websites of opposition political parties and news media outlets, including media from Papua and West Papua that had a history of documenting human rights abuses.

The lack of transparency surrounding the purchase of the spyware tools has created an atmosphere of “terror” as “anyone can be a target”, Nenden of SAFENet said.

“As a result, people will self-censor. This really threatens the future of democracy in Indonesia, because people are becoming increasingly afraid to express their opinions,” she said.

Sasmito argued that surveillance agencies mimicking news outlets could also harm the local news industry “because people cannot differentiate whether a particular media is real or not”.

“This is detrimental to the news [industry], because people view media sites as vulnerable. This is quite dangerous as it can further lower public trust in the media.”