“Deep down I still want to have a baby. But every time we learn that it has failed we’re so sad and depressed, the world crumbles and I feel I’m a failure.”

Pressure from her in-laws and a husband desperate for an heir has compounded the emotional toll, she says, with months of each year lost to punishing regimens of hormone injections, medications, weight gain – and the painstaking process of picking up the pieces after her hopes come crashing down when treatment cycles fail.

So far, she has spent some 5 million baht (US$136,000) on the procedures: a small fortune for her, but a drop in the ocean of the multibillion-dollar business that is baby-making.

But in the pay-to-play world of ART, where you live – or are willing to travel to – determines how much you have to spend.

“Let’s say you put in everything you can throw in to maximise the pregnancy rate, it’s not going to be cheap,” said Dr Colin Lee, CEO of Malaysia-based Alpha IVF Group, which has just listed on the Malaysian stock exchange. “The entire IVF process is quite complicated.”

IVF clinics have been sprouting up across the region as couples look to have children later in life, reflecting wider social changes surrounding choice, economics and narrowing gender disparities.

The need for affordable, clearly signposted fertility treatments is growing acute, experts say – as they urge governments to step up the subsidies available to women who want to have children.

Infertility: the stresses of IVF, and why there’s always hope

Infertility: the stresses of IVF, and why there’s always hope

In Australia, one in every 18 babies are born using IVF, a report published by the University of New South Wales last year revealed. Thanks to government funding most patients who want it “are in a position to now access IVF”, said Luk Rombauts, medical director of Monash IVF and professor at Monash University in Melbourne. “Other than the very remote areas of Australia, access is generally good for most patients.”

Similarly in Singapore, government programmes that help cover the cost of fertility treatments part-fund thousands of ART cycles every year – 10,800 in 2021, according to the latest Health Ministry data.

Baby-making breakthroughs

The business of making babies started more than four decades ago, when the world’s first ‘test tube baby’ – Louise Brown – was successfully delivered at Oldham General Hospital in England as midnight approached on July 25, 1978.

The IVF landmark sparked frenzied debate over the ethics of doctors ‘playing God’ with the fundamentals of human life, but also spurred a social and scientific revolution that changed the potential options for millions of childless couples overnight.

Since then, an estimated 12 million babies have been born using the fertility treatment. Asia’s first IVF baby was Samuel Lee, a Singaporean born in 1983 thanks to the pioneering work of Professor Shan Ratnam.

The breakthrough gave hope to childless couples across Asia and has since spawned a multibillion-dollar industry, backed by private equity and listed companies, which brings the miracle of life to would-be parents.

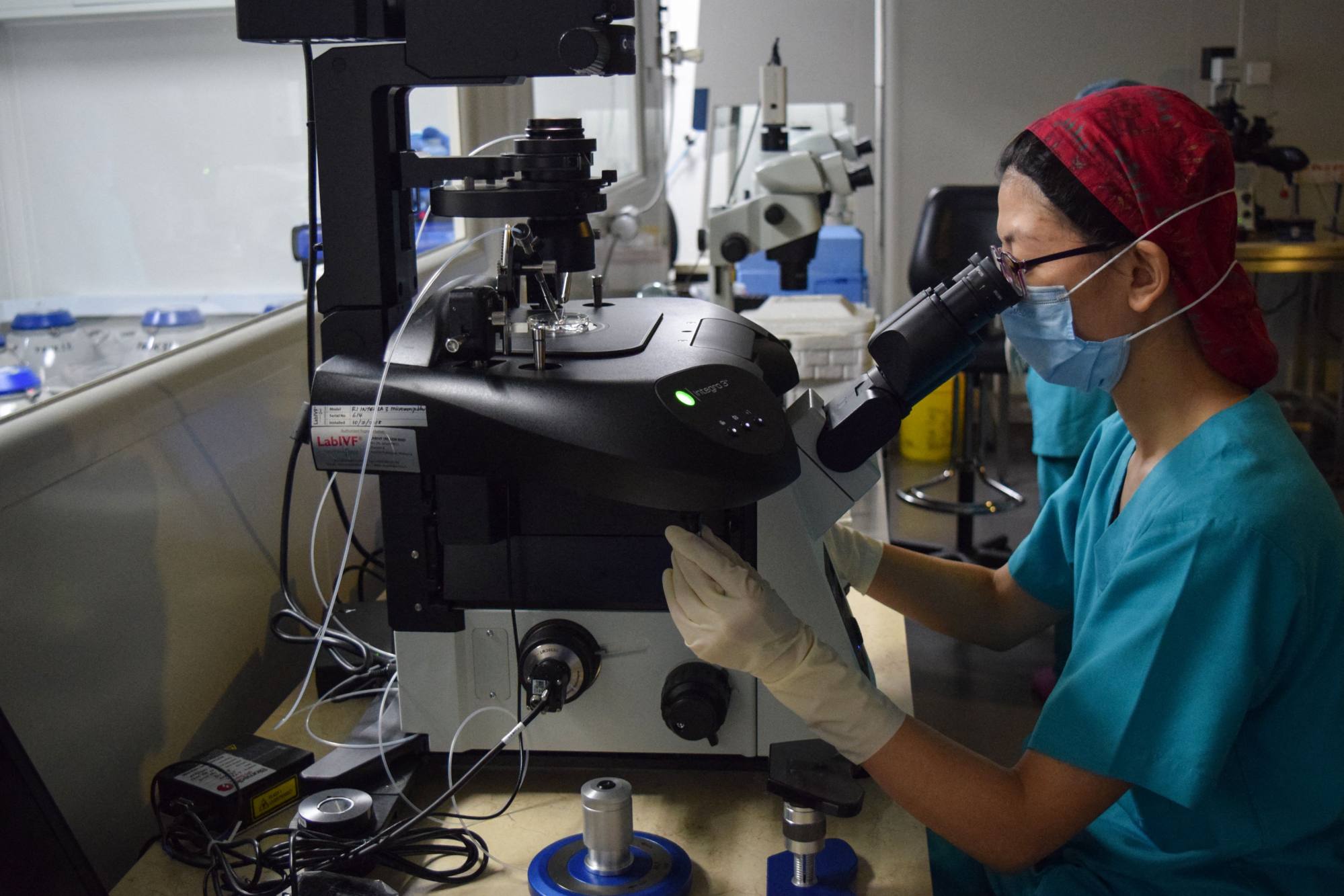

IVF treatment involves the use of hormone injections to stimulate the ovaries into producing multiple eggs, which are then retrieved and fertilised with sperm outside the body. After fertilisation, the resulting embryos are monitored and nurtured for a few days before being implanted into the womb, increasing the chances of a successful pregnancy.

“There are hundreds, if not thousands of parts involved and if there is no economy of scale then the cost of doing IVF for the clinic is actually very high,” said Alpha IVF Group’s Lee.

To make the process financially viable, chains of IVF business have sprung up offering one-stop shops for egg freezing, treatment cycles and medical care.

Even then, though, a successful birth is far from guaranteed, with age largely determining outcomes. IVF succeeds in around 30-35 per cent of cases for women aged under 35, dropping to as low as 7-10 per cent for women over 40.

Egg freezing, which limits the number of times a would-be mother has to undergo minor surgery for the egg-retrieval process, is currently a political hot potato in the US, after the Alabama Supreme Court ruled earlier this year that frozen embryos are legally equivalent to living children – making their destruction murder.

Yet as Asia’s demographic decline deepens, any such ethical and religious debates have been pushed into the background, with governments instead focused on providing fertility services while clinics attempt to woo customers using aspirational advertising and social-media algorithms.

Malaysia is hoping to capitalise. Home to 10 of only 30 fertility centres globally that have been certified by the Australia-based independent Reproductive Technology Accreditation Committee, the country aims to become Asia’s “fertility hub”, according to the Malaysia Healthcare Travel Council, an agency of the health ministry.

Growth potential is particularly strong among Southeast Asia’s 700 million-strong population, many of whom remain underserved by the region’s fertility industry, Alpha IVF Group’s Lee said.

Alpha IVF Group already has four fully-fledged facilities, including one in Singapore, and plans to open two more centres in Southeast Asia by May next year – one of which will be in Indonesia.

Emotional support

Most couples are aware of the social stigma and familial disappointment that can accompany being childless in Asia, but less discussed are the downsides of ART treatments, or the potential risks involved.

In recent years, a number of support groups have been set up to fill this information void.

“Honestly, I went into IVF thinking it was going to be easy and I just needed to do it one time and succeed,” said Kimberly Unwin, director of Fertility Support SG, a Singapore advocacy and advice group for couples seeking help with having a baby.

Many would-be parents are ill-prepared for the financial, physical and emotional toll of undergoing ART treatment, she said.

I went into IVF thinking it was going to be easy and I just needed to do it one time and succeed … little did I know

“Little did I know that going through fertility treatments was actually really tough. Injecting myself with needles was hard because my brain was telling me not to, but I had to do it despite the pain, six times a day for 12 to 14 days in a row,” Unwin said.

“Mentally, my emotions were all over the place – one moment I felt OK, and the next, I was crying. I also gained a lot of weight … I’m not sure if this was from stress or the medication.”

Eventually, after three years of trying, she became pregnant with her third child – a baby girl – who she welcomed to her family in May last year.

Unwin founded Fertility Support SG to help guide other couples through the process, providing data on success rates and advice on navigating the complex medical procedures and tribulations it can involve.

She offers what she calls “much-needed emotional support that is often overlooked on this challenging journey”, through Instagram posts, WhatsApp group chats and face-to-face monthly meetings serving as connection points for couples going through fertility treatments.

“What’s even more touching is that some of the women we’ve assisted have joined us as volunteers, eager to pay it forward and help others,” Unwin said. “This sense of community and support is incredibly heartwarming.”

Aware of the price barrier to fertility treatment, Singapore’s government has offered financial assistance for ART since 2008 and is looking at boosting the amount available for citizens and their partners. Eligible couples can currently receive co-funding of up to S$7,700 (US$5,650) per fresh cycle and S$2,200 per frozen cycle under the scheme – but only for three cycles.

The clamour for more state subsidies is growing louder, from Thailand, where the health minister has floated the idea of helping Thais with fertility treatments, to Australia, a country known for its progressive laws and support structures for people seeking IVF and related therapies.

Fertility rates have slumped in both Australia and New Zealand in recent years, but babies born following ART treatment have hit record highs – with more than 20,000 in 2021, according to the University of New South Wales, citing the latest year for which figures are available.

The Australian government provides coverage for IVF through its publicly funded universal healthcare insurance scheme Medicare, while publicly funded fertility treatments are also available to eligible patients in New Zealand.

Despite subsidised access, however, the role that age plays in the success of IVF can leave women on a merry-go-round of treatments, hoping for a breakthrough but painfully aware that their odds diminish as each year passes.

I think the only people who can understand you are others going through the same thing

Kate, who lives in Western Australia, wasn’t sure she wanted to be a mother until she was in her thirties – a delay that reflects shifting social values and priorities in society as a whole.

“I didn’t have the traditional path of getting married and starting a family … I’m still single, but I only felt a few years ago that I was ready to become a mother,” the 36-year-old said, requesting to go by her first name only.

She is now on her second round of IVF, financing the treatments with Medicare coverage alongside some help from her parents.

But she worries that the “excruciating” treatments may become too much to bear if they don’t succeed soon.

Why IVF and egg freezing are but a dream for many women in Hong Kong

Why IVF and egg freezing are but a dream for many women in Hong Kong

“Being a single mum can make this process feel very lonely,” she said. “It’s hard to always try and be positive and keep a smile on your face … I think the only people who can understand you are others going through the same thing.”

The friends she has made through IVF support groups on social media help her to carry on.

“I know that I will have to keep trying, but it’s difficult not to lose hope,” she said. “Sometimes you wonder whether this is something that’s just not meant to be for you, and I have to shake that thought away.”

Additional reporting by Sophie Chew