“The big hull also enables the ship to have huge fuel reserves, which will allow it to stay at sea longer, as well as carrying more missiles, both air-defence missiles and strike weapons,” he said.

At 120m (394ft) from bow to stern, with a 25m beam and displacement of 12,000 tonnes, the warships will be among the largest and, thanks to the US-made Aegis fire-control system, also the most capable missile defence platforms in the world.

The single-engine variant of the power plant is already tried and tested in Japan’s Mogami class of stealth frigates. It also powers the Type 26 frigates and the Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers operated by the British navy, and the US navy’s Freedom-class littoral combat ships and Zumwalt-class destroyers.

“Our aim is that within the next decade, it will become the dominant engine of choice across the Pacific Rim,” Rolls-Royce said in its statement.

Japan first deployed an Aegis warship in 1993, with the Maritime Self-Defence Force’s Kongo the lead vessel in the four-ship class. Another four upgraded ships have been added to the fleet since, most recently the Haguro that was commissioned in March 2021 and is based at Sasebo in Kyushu.

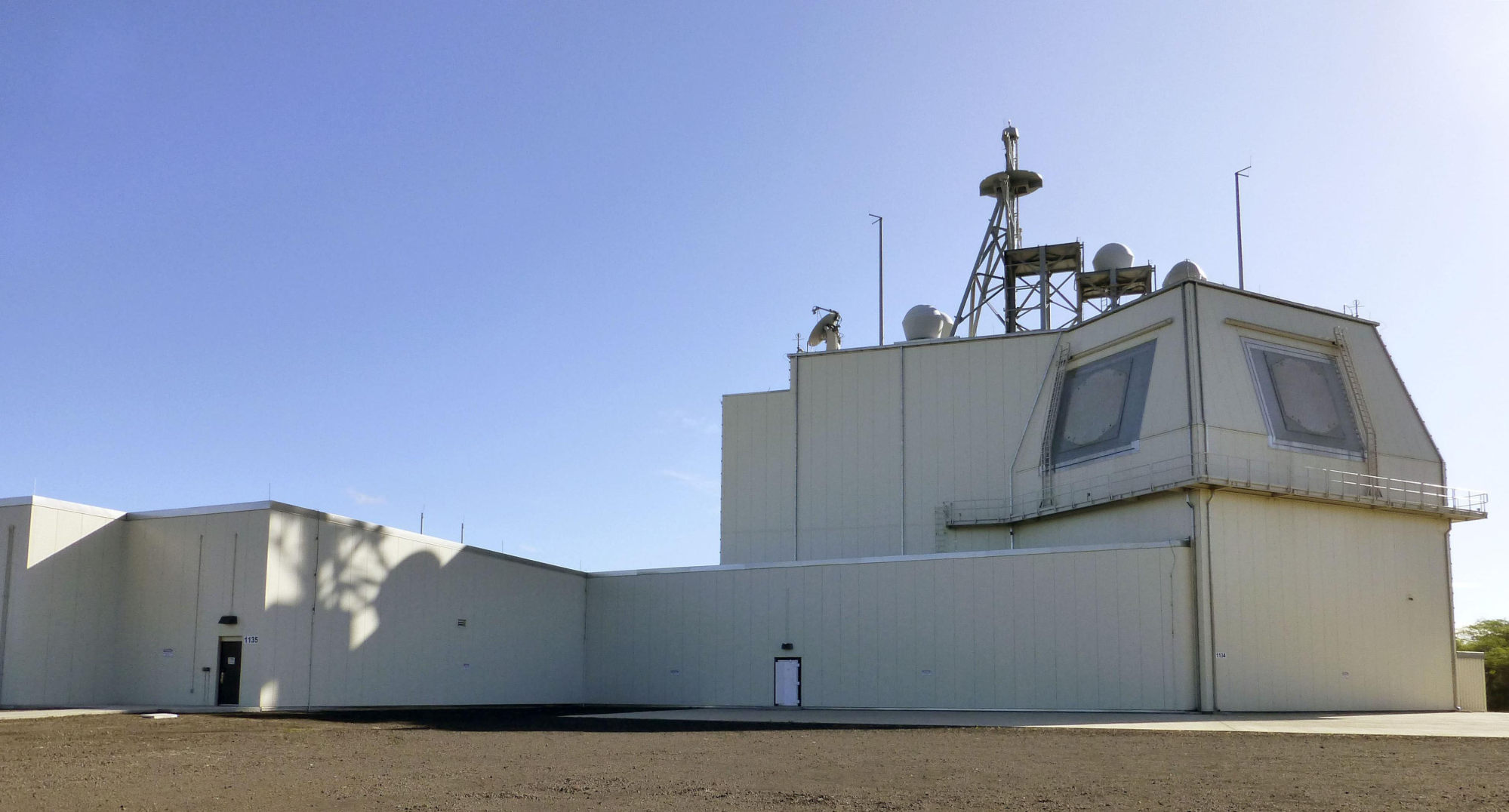

Tokyo decided to develop a new class of Aegis warships after the abrupt cancellation of the land-based Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defence system in 2020. The plan had been for the construction of two coastal bases that would incorporate radar systems, vertical launch cells and SM-3 interceptor missiles.

Plans for the facilities in Japan met strong resistance from nearby communities, concerned that they would be targets of attacks or that components could fall in the area during tests or actual launches.

There have been no firm reports on how many cells the ships will have, but they could rival the Chinese navy’s Renhais class, which each have 112 missile cells.

They may even surpass the US navy’s 9,800-tonne Ticonderoga class cruisers, which have 122 missile cells but are being retired.

The benefit of a vessel conducting anti-missile operations includes greater mobility and difficulty for an enemy to locate. Such a vessel would also be marginally closer to an incoming missile, giving it more time to intercept it.

The drawbacks include greater vulnerability once the ships are detected, and that two vessels would be insufficient for complete cover.

The choice of Rolls-Royce underlines the growing security links between Japan and Britain, Mulloy says, pointing out that a British navy task force led by HMS Queen Elizabeth visited Japan for exercises in 2021 and is scheduled to return again next year.

Two British patrol craft are also based in Japan and are taking part in multinational efforts to halt North Korean ships trying to evade sanctions.

Greater security and weapons systems development are becoming more commonplace, although there are limitations on the countries that Western governments are willing to work with.

“Britain has worked with China in the 1970s and 1980s. Rolls-Royce sold Spey turbofan engines to China when London was cosying up to Beijing during the Cold War,” Mulloy said.

France was similarly selling helicopters and missiles to China, while Italy, the US and others were also selling hardware to Beijing, he told This Week in Asia.

“But that has completely stopped now,” Mulloy said.

“About five years ago, France was pushing for the embargo that was imposed after Tiananmen Square in 1989 to be lifted, but now the whole perception of China has changed in Europe and the West.

“Since the outbreak of the Ukraine war, the West has realised that it needs to do much more to build up its own defences and, at the same time, to be much more careful about who it cooperates with overseas,” he said.

“Today, it is impossible to do business in the defence sector with China.”