In each case, the building remains uninhabited.

Seth Sulkin, founder of property developer and asset management firm Pacifica Capital KK, said the “primary reason” for homes in Japan being left empty “is that the population outside Tokyo is falling rapidly, especially in areas such as Tohoku and Hokkaido, and old people are simply abandoning their homes”.

“In addition to that, it is very difficult to recycle these properties because of the inheritance and property title systems in Japan,” he told This Week in Asia.

When it comes to property inheritance in Japan, a deceased person’s spouse is legally entitled to half of a property, with the remainder being divided among their children. But if an inheritor cannot be located or refuses to sell their share, there is no solution, according to Sulkin.

Once primarily seen in rural areas most affected by worsening population decline, akiya are now increasingly being found in the suburbs of major cities. In an effort to curb the growth of abandoned homes, local authorities were granted the power in December to withhold tax breaks from owners who fail to take necessary measures to maintain the buildings and prevent their collapse.

The idea is to encourage owners to either repair and use the homes, or sell off the land for developers who will make better use of it.

Though it may seem puzzling that such a paperwork-oriented country could lose track of property inheritors, Takayuki Morimoto, deputy head of sales at the Tokyo-based Broad Brains property agency, said the reality is that it happens all too frequently.

“It can be complicated when people die and no one wants their home and yes, it sounds strange, but it can be difficult to work out who owns these places,” he said. “But the government has started to move because they have realised that they are losing out on tax revenues.”

For the akiya issue to be effectively addressed, Sulkin says the government needs to adopt a more assertive approach – including passing laws that empower local authorities to take ownership of abandoned homes and sell them to developers.

“A mechanism is needed to enable governments to take control of and then auction off these buildings because if nothing is done, then the problem is only going to get worse as Japan’s population is going to continue to decline and there are going to be more and more empty homes,” he said.

Part of the problem is that Japan lacks an established model like the practice referred to in Britain as “buy-to-let”, whereby smaller investors rent out a handful of flats. Instead, the rental and development markets are overwhelmingly controlled by larger companies.

“When my mother died about seven years ago, we never really thought about developing or renting out her home,” said Tomoko Oono, a former bank worker from Saitama prefecture, north of Tokyo.

“She had lived there for a long time and it was old and in a poor state of repair, so it would have cost a lot to demolish and then build again – and we don’t have any experience of doing that,” she said. “We decided the best thing to do would be to just sell the land.”

While she doesn’t regret selling the property, as it greatly boosted her family’s savings, Oono says she was taken aback when she later drove by the plot and discovered that the developer had managed to squeeze two homes onto the land.

“My mother had a garden and the land was on a corner so the developer was able to put two houses with no gardens in there,” she said. “I think they saw an opportunity to make a bigger profit and took it.”

Yet there are some enterprising individuals who have identified the business opportunity in these often overlooked properties – snapping up those in the most desirable locations or that have the greatest potential.

In 2020, Anton Wormann bought a tumble-down akiya that had been empty for more than a decade and transformed it into a cosy property that he now rents out on Airbnb.

Wormann, who is originally from Sweden, said he was walking past the 100-year-old building one day and started talking to the four siblings who had inherited the property and were trying to tidy it up.

When he suggested he would like to buy it, they responded, “Really? You want to buy this piece of rubbish?” he recalled.

The family had no desire to redevelop the site and was keen to dispose of the building, in the hip Sangenjaya district of west Tokyo, so the transaction was relatively straightforward.

Gutting the interior and installing an entirely new kitchen, modern bathroom, living space and bedrooms took a year – and a sizeable chunk of his savings. But Wormann says he learned a lot from the experience, and admits he’s been bitten by the bug.

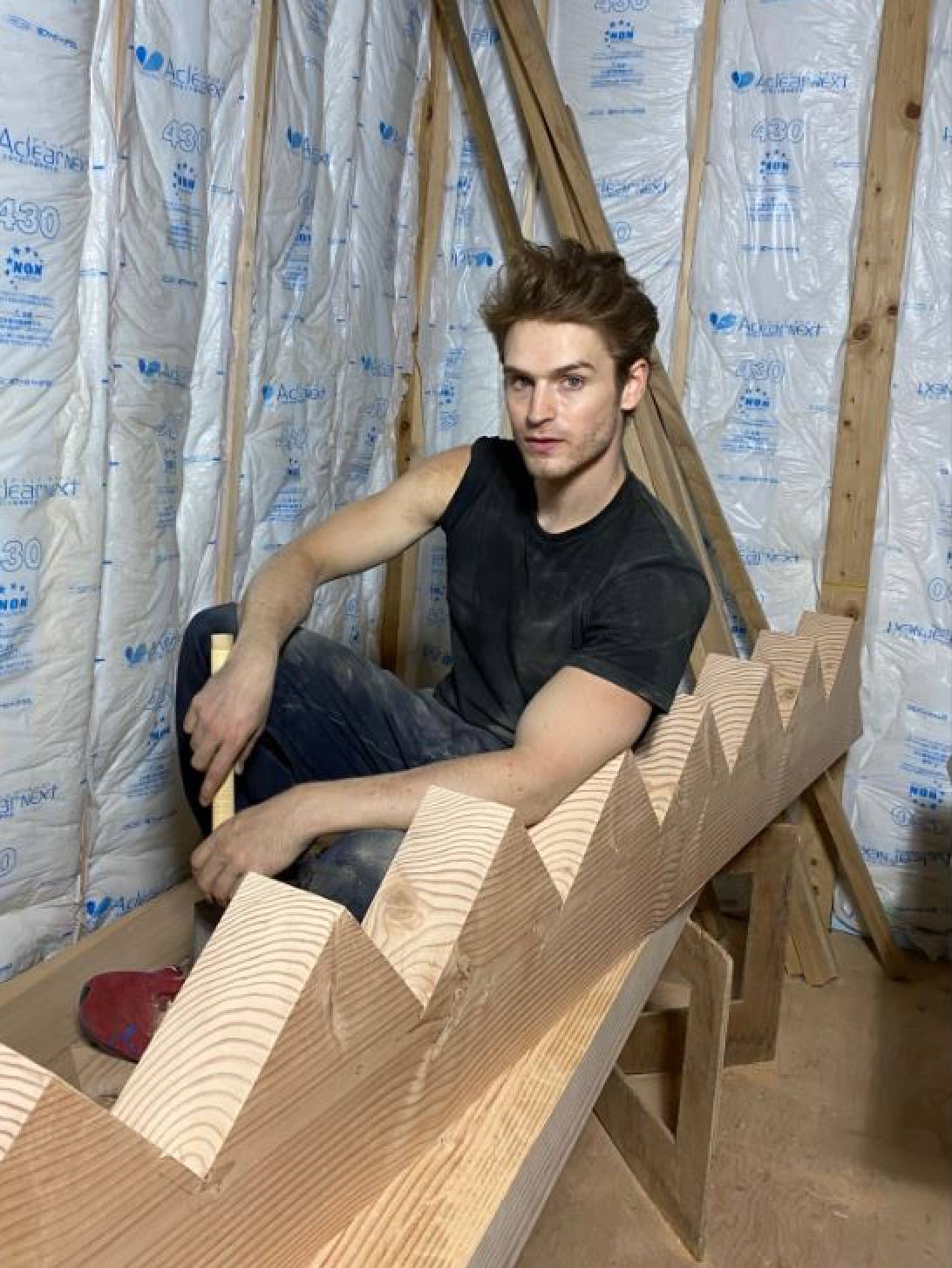

“I have been working on another akiya in the Shinjuku district and I am hoping to have it ready in about five months,” he said, estimating he will have spent 25 million yen (US$159,000) on the project, including the initial purchase price, by the time it’s completed.

“I see huge potential in the akiya sector in Japan,” he said. “It is cheap to buy homes here and, if you wanted, you could buy an entire village in the most remote parts of the country. But it can be hard to sell up again, so it is better for someone who is planning to stay in Japan for a long time.

“I also think there are lot of opportunities for akiya in the tourism sector and as a way of helping rural parts of Japan to survive.

“But for me, I just enjoy turning something that no one else wants into something cool.”