More than 300,000 people like Pui use the Johor–Singapore Causeway every day, making it the busiest international border crossing in the world. The 1km-long embankment not only carries a continuous flow of commuters, day trippers and pupils in either direction, but also commodities and goods – and has done so for the past 100 years.

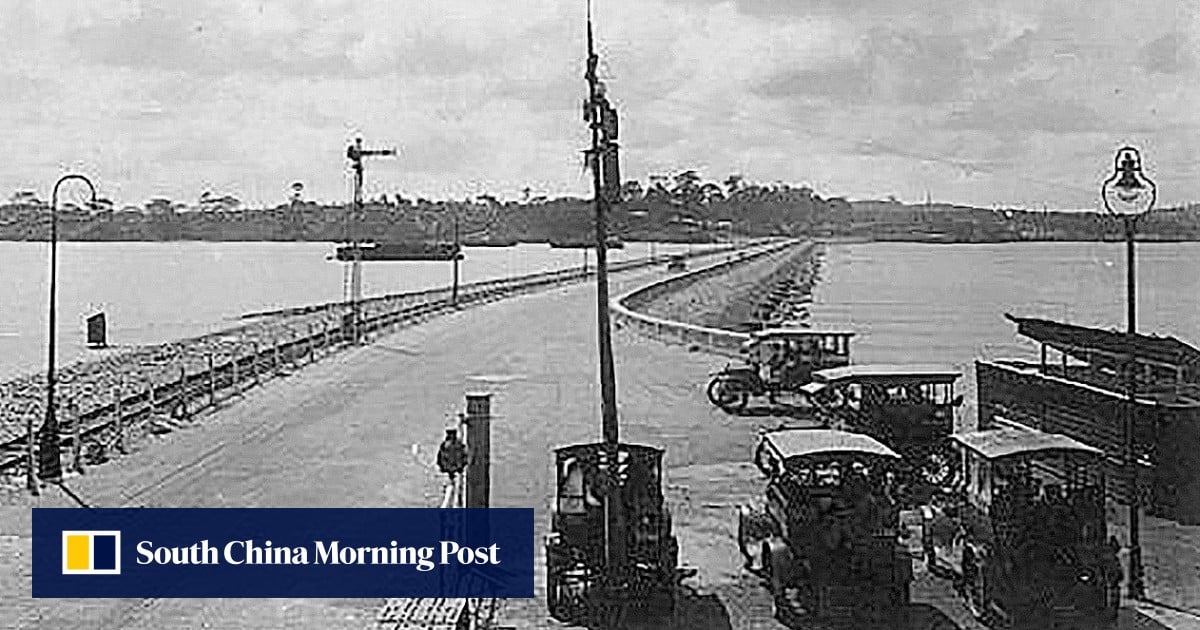

Officially opened on June 28, 1924 after almost five years of construction, the causeway was intended to ease pressure on the ferries and other vessels that were previously the only way of crossing the Johor Strait.

At the time, the land on both sides of the water was part of British Malaya – Singapore as a colony and Johor as one of the Unfederated Malay States – with a steady stream of rubber and tin heading south, while leisure excursions went in the other direction. At weekends especially, travellers would head north to Johor Bahru to try their luck at its so-called gambling farms, as betting was then illegal in Singapore.

As early as 1912, the high cost of running ferries across the strait was being cited as a reason to find an alternative solution. These calls only grew louder as passenger traffic and goods volume increased. The ferries soon started struggling to keep up with rising demand – until, in 1919, the causeway project was officially approved.

Though considered more affordable and easily maintained than a steel bridge, the causeway was still a technological achievement, being heralded as a “great engineering feat [that] ranks high even in an age of high achievement” by British colonial administrator Laurence Guillemard at the inauguration ceremony, which was attended by Johor Sultan Ibrahim Al-Masyhur and more than 400 guests.

“It stands before you as a monument to the skill and patience of those who made it and the foresight of those who planned,” Guillemard said, declaring the causeway open.

Connector that separates

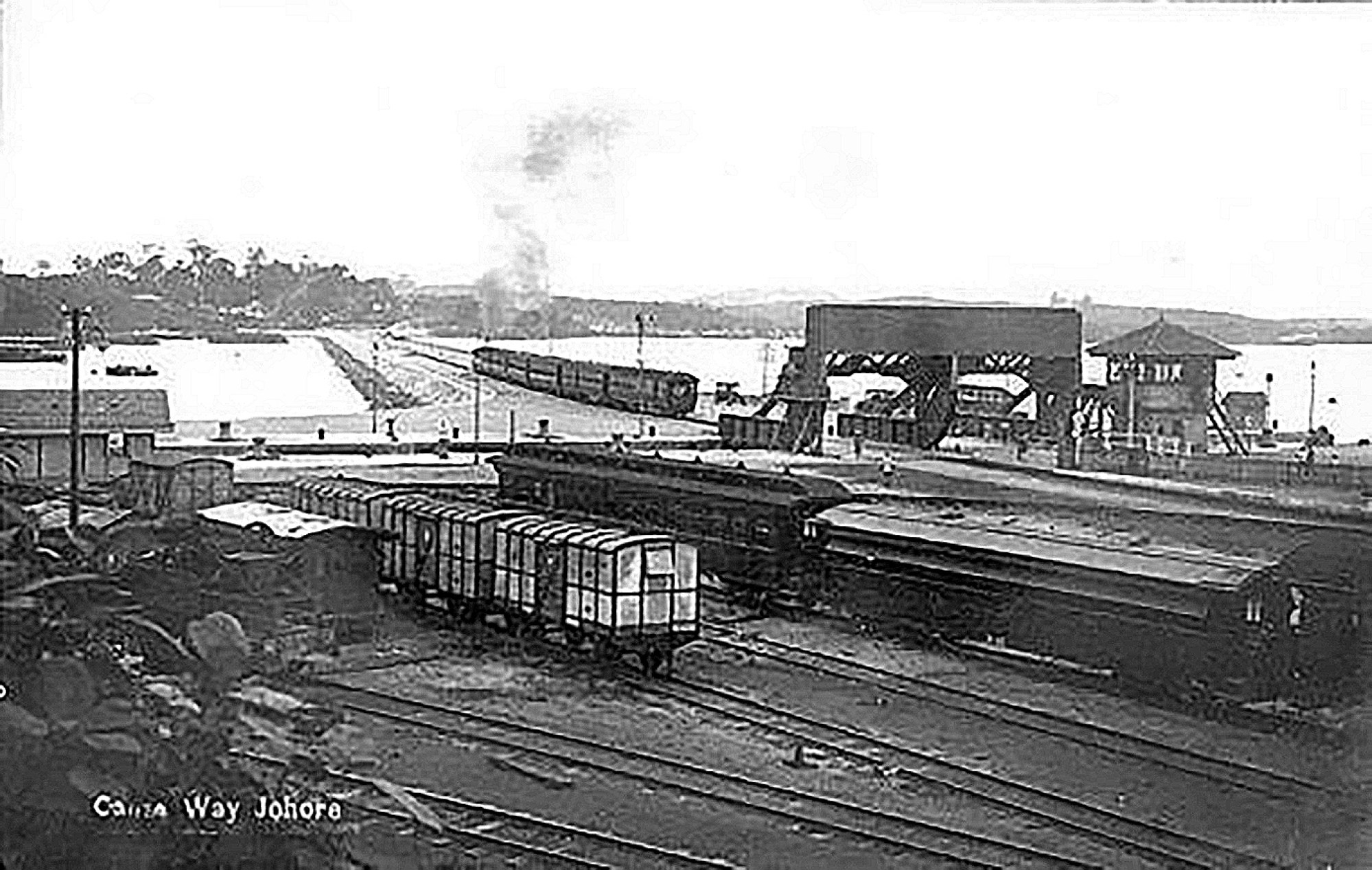

The causeway’s opening established a direct rail link between Singapore and the Malay Peninsula for the first time. But the accompanying road soon proved much more popular than the railway as the main means of crossing the strait.

It was the roadway that most interested the sultan of Johor, according to Dr Serina Rahman, a lecturer in the National University of Singapore’ Southeast Asian Studies Department. The sultanate funded most of the road’s construction, while the British prioritised the railway.

“It was the sultan’s vision that expanded what the British essentially only wanted for trade,” Serina said. “That really opened the door for relations to be strengthened.”

Certainly, the crossing helped to boost connectivity and foster a common Malayan identity on both sides.

But its construction also curtailed the traditional way of life of coastal communities living along the strait, such as the Orang Seletar. It blocked the natural flow of water in the waterway and disrupted the movement of marine life which these communities, with whom Serina now works, had long depended on.

Originally, small vessels were able to traverse the causeway through a lock channel with an electric bridge that lifted up to allow them to pass, but this was blown up by Allied forces during World War II in a failed attempt to deter Japanese forces from invading Singapore. When the causeway was eventually repaired, the local channel was filled in – permanently dividing the strait.

Another division arose in 1965, the year Singapore separated from Malaysia after briefly uniting with it in a federation to gain independence from the British. This transformed the causeway and the strait into an international border, which could no longer be freely crossed.

“Not just the indigenous people, but the locals who were so used to going back and forth – generations and hundreds of years of travelling without borders, suddenly what they have been doing is illegal. And the British began that. So while the causeway connects, it also separated,” Serina said.

Barometer of relations

The establishment of immigration checkpoints on both ends of the causeway by 1967 did not stop the flow of goods and people, however.

Between 1958 and 1988, average daily traffic grew more than sixfold, from around 7,000 to over 43,000 vehicles. The resulting congestion led to the roadway being widened with additional lanes and the checkpoints being expanded.

But the “causeway jam”, as it is known, continues to this day – and it can stretch on for hours. In 1998, a bridge known as the Second Link opened to connect Tuas in the western end of Singapore to Tanjung Kupung in Johor. The causeway, however, remains the more popular connection.

At the opening ceremony of the Second Link, Singapore’s then-prime minister Goh Chok Tong acknowledged how the causeway had become more than just a piece of transport infrastructure.

“It developed into the foremost conduit for the movement of goods and people between Singapore and Malaysia,” he said. “It became the symbol of the close historic ties between our peoples.”

Even as it serves as a barometer for cross-strait relations, the causeway has also become intertwined with the everyday lives of people on both sides.

Malaysia and Singapore are major trading partners, as evidenced by the vast volumes of goods – from eggs, vegetables and other foodstuffs to specialist goods like ornamental fish and semiconductors – that move across the causeway. Tens of thousands of Malaysians also commute daily to work in Singapore’s manufacturing and service industries, while Singaporeans flock to Johor Bahru on the weekends and holidays for leisure.

This cross-border flow became acutely visible during the pandemic when travel restrictions abruptly shut it down – though the movement of commercial cargo continued.

“Covid reinforced the economic linkages across the causeway,” said Dr Shaun Lin, a political geographer who lectures at NUS College. “But people also had to make a hard decision on whether to move back to Malaysia or stay on in Singapore.”

When the border finally reopened after two years, long queues of vehicles and people showed up at both sides of the causeway, cheering and sounding their horns. Crossings have since returned to and surpassed pre-pandemic levels, with a record half-a-million travellers using the causeway and Second Link in a single day in March.

The causeway has become a collective social memory of ups and downs

“The causeway has become a collective social memory of ups and downs,” Lin said. “Its function is economic for sure, but there tends to be quite a lot of overlooked social connections too.”

He compared the causeway to the Oresund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden, which likewise connects two countries but also enables road and rail transport to a much wider region.

“While it connects both sides of the border, it enables continuous travel to somewhere further,” Lin said. “Don’t just see it as a 1km link. It’s definitely much more than that.”

Stronger ties ahead

Singapore relies on its larger northern neighbour as a source of labour, while Johor receives a slew of investments from the city state in return. As of 2022, Singapore was the Malaysian state’s second-largest foreign investor and has also helped it attract Chinese developers to construct a number of mega developments.

Princess Cove, a waterfront development right next to the causeway, is one such example. It is set to offer a mix of hotels, office space, shopping centres and apartments advertised as having “magnificent” views of Singapore’s skyline. Around 40 per cent of the buyers so far have been Singaporeans, according to Guangzhou-based developer R&F Group, with Malaysian, mainland Chinese and Taiwanese investors rounding out the top four.

“Johor’s urban development is very much intertwined with the causeway and Singapore rather than the capital in Kuala Lumpur, which is much further away,” he said.

“The impact of Singaporeans crossing over to shop and capital from Singapore is more immediate … It is pretty evident that Johor, through the causeway, attracts foreign investment because of its proximity to Singapore.”

Meanwhile, the governments of Singapore and Johor are working to make travel across the causeway as seamless as possible.

Singapore, meanwhile, is reclaiming land around the causeway to expand the Woodlands Checkpoint, aiming to cut average immigration clearance times down to just 15 minutes from an hour of more during peak travel periods.

But this push towards greater integration only formalises what many in Singapore and Malaysia have long recognised: that the causeway is an essential link, for the past 100 years and into the future.

“The market in Malaysia is big. Singapore lacks land, Johor got land,” Pui said. “It’s mutual lah.”