Built over a century ago in 1921, the ‘Friendship Bridge’ between Rantau Panjang in Malaysia and the town of Su-ngai Kolok in Thailand, is just 65 metres (213 feet) long.

But the gap also represents competing visions for the connectivity of the Mekong and the Malay Peninsula.

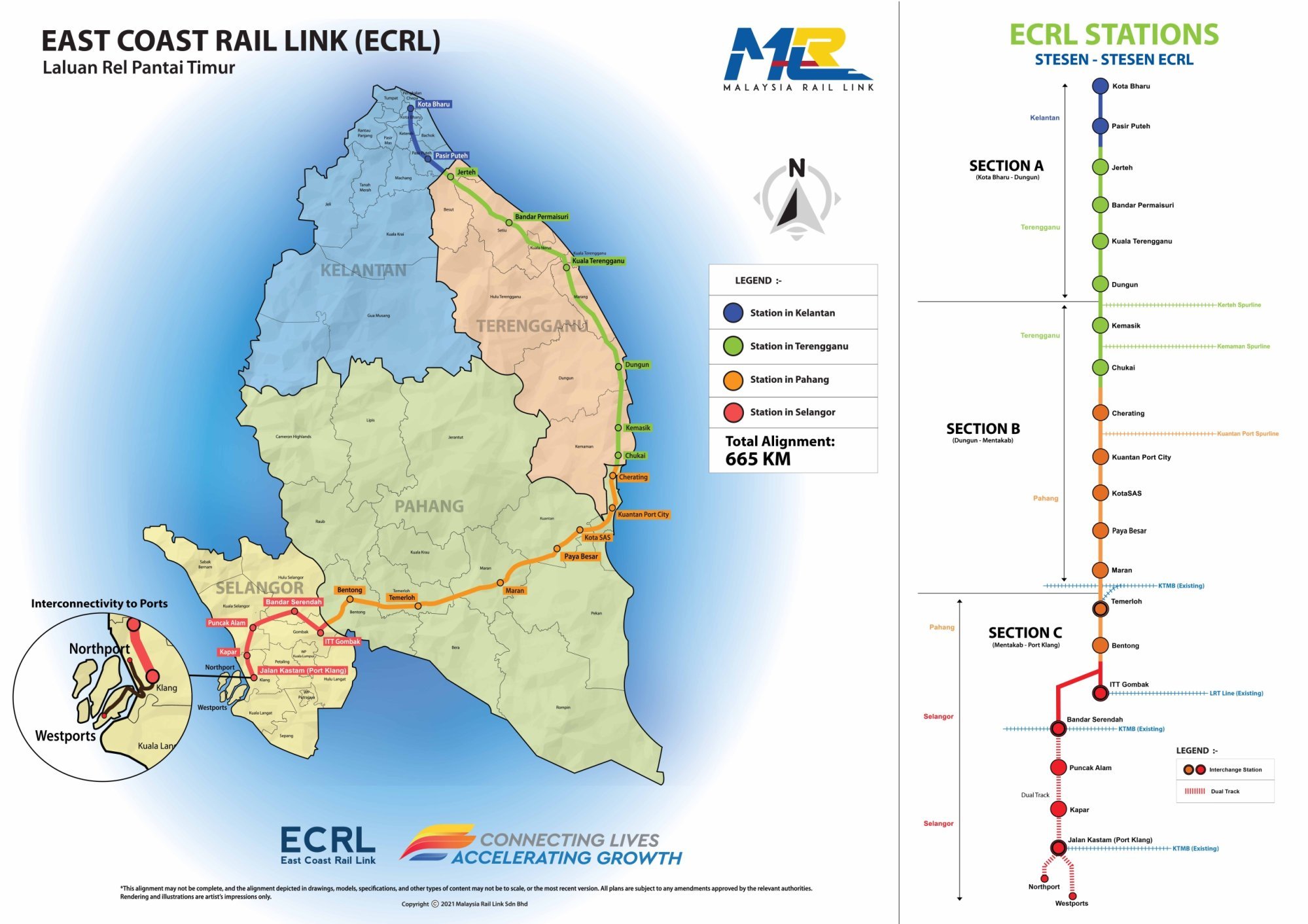

On Malaysia’s side, the plan is to construct the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) from the shipping hub of Port Klang on the west coast to the eastern states of Kelantan, Terengganu and Pahang, replacing an obsolete colonial-era line with the latest rail infrastructure built by Chinese companies.

It would be the penultimate step towards a Kunming-Singapore railway, crossing Laos, Thailand and Malaysia at speeds of up to 160km/h, and a chance to seamlessly bind the regional economies of hundreds of millions of people along the network.

A line already cuts through Laos and – after years of arm-wrestling over price and rail type – Thailand is laying tracks running south to Bangkok.

But the neck of the country leading to Malaysia is the missing piece southwards.

For now, Thailand – which is central to a Pan-Asian rail route through its territory with borders straddling Laos and Malaysia – has other priorities.

His proposal – if realised – potentially poses a major economic threat to Malaysia and Singapore, whose ports are situated along one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

Centuries-old pipe dream

The route carries around 30 per cent of the world’s trade.

By the end of the decade, this number is projected to rise to 50 per cent, with shipping expected to exceed handling capacity as China knits more tightly into Southeast Asia’s economies.

Thailand’s landbridge, with deep seaports at Ranong on the Andaman to the west and Chumphon on the Gulf in the east, could ease the bottleneck around the Malay Peninsula with an overland road and rail link. It will turbocharge Srettha’s ambition of making Thailand the premier logistics hub in Southeast Asia.

“Constructing a megaproject that links the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea to the world is important to lessen congestion [on the Strait of Malacca],” Srettha said in January during a visit to Ranong.

“It will also bring development to the country as it can influence more foreign investors.”

The landbridge could take a chunk from the Port of Singapore and Malaysia’s Port Klang, the world’s second and fourteenth busiest cargo ports, respectively, and channel more intra-Asia cargo flow via Thailand.

The mammoth task of linking the Andaman and the Gulf has thwarted big dreamers over the centuries.

As early as 1677, King Narai of the Ayutthaya Kingdom in present-day Thailand looked at the map of Southeast Asia and plotted to cut a canal through the Malay Peninsula, allowing ships to circumvent the long travel south across the Strait of Malacca.

Such plans have fallen apart due to projected astronomical cost, political instability and complex geographical factors – a canal would physically separate Thailand, which already struggles with a separatist conflict in its Malays-majority southernmost provinces.

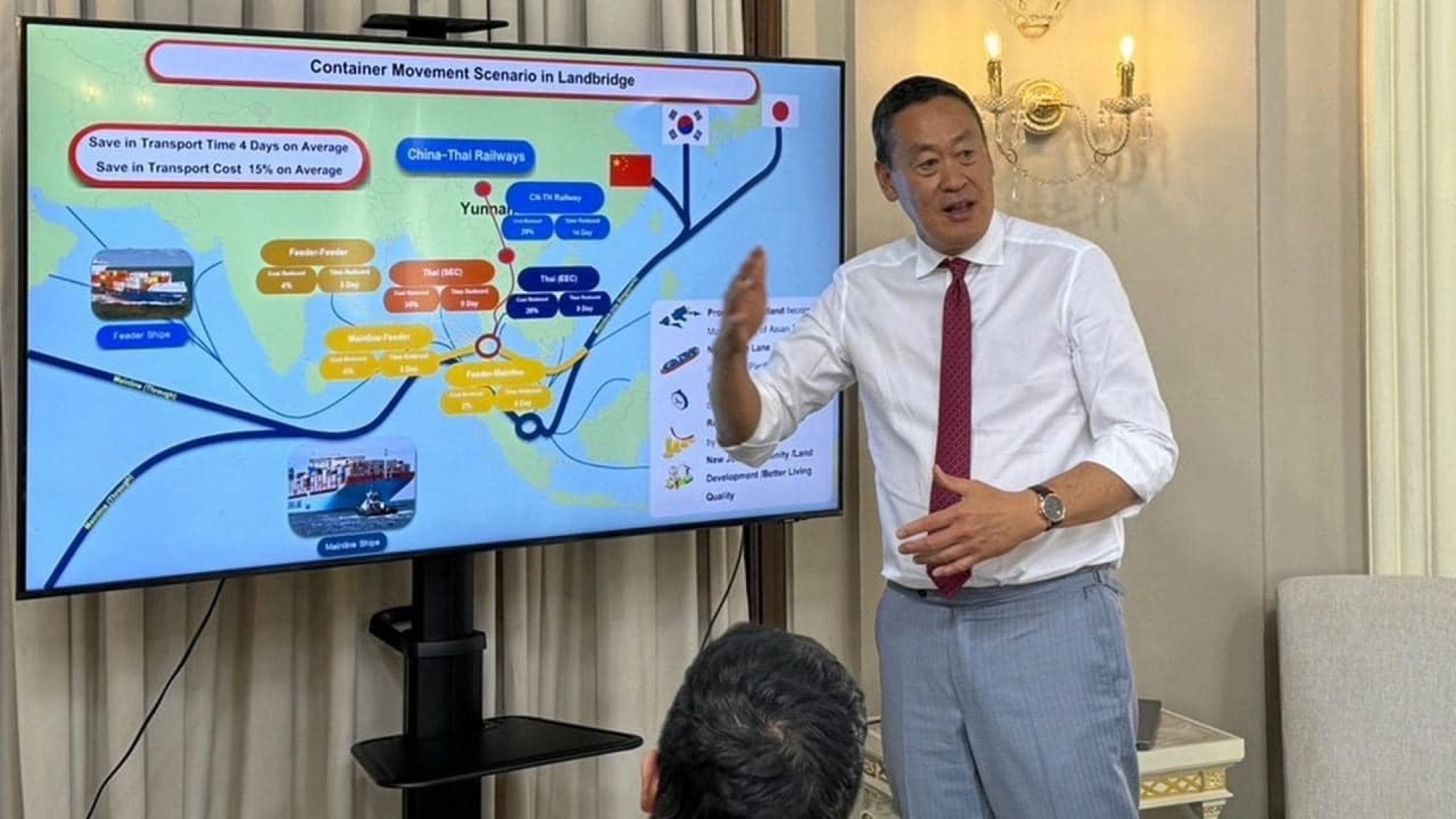

But last year, Srettha shared his bold and new vision at the third Belt and Road Initiative Forum in Beijing. Instead of a canal, Srettha produced a scribbled map showing two ports on the west and east of the peninsula – on Thailand’s side – connected by rails and roads.

Since the event, Sreetha has been busy drumming up interest among international investors.

Thai authorities project that the land bridge will cut transport duration by an average of four days and lower shipping costs by 15 per cent compared with current shipping routes via the Strait of Malacca.

But logistics experts have cast doubt on Thailand’s upbeat forecasts given the vast tonnage of cargo which would need to be hooked on and off container ships on both sides of the landbridge.

“Thailand has many times suggested the landbridge project,” Marco Tieman from supply chain strategy consulting & research firm LBB International told This Week in Asia.

“It has always been too costly, with security issues and environmental impact [among the key] concerns. So I don’t see this happening.”

Malaysia’s rail proposal is “a better concept” than Thailand’s landbridge, he added.

Investors may also be treading carefully, aware that Thai governments and policies can change fast.

Since abolishing absolute monarchy in 1932, the kingdom has had 30 prime ministers with only several former senior military figures – Plaek Phibunsongkhram, Prem Tinsulanonda and Prayut Chan-o-cha – having served more than five years. Former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who founded the Pheu Thai party and is still its most influential figure, was the only elected leader to complete a term without a coup or being taken down by the courts.

Battle of the big plans

While Thailand bangs the drum for the landbridge, Malaysia and Singapore are pushing ahead with their connectivity projects.

Malaysia’s ECRL project, once the star of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, is regaining steam as construction continues on schedule for a projected start of operation in 2027 – several years ahead of Thailand’s timeline for its landbridge 700km further north.

In Kelantan on a recent feasibility trip, Loke – along with an entourage from Malaysian Rail Link (MRL), the ECRL’s operator, and Malayan Railway, the operator of the old network – said Malaysia’s focus would be on integration with existing infrastructure.

“There already is a railway line connecting countries from China to Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia,” he said.

“We are looking at further integration, not only in the railway track but in terms of customs clearance, intergovernmental understanding, for trade to flow between the countries.”

Like the Thai landbridge, the rail link will connect Malaysia’s main transshipment facilities in Port Klang on the Strait of Malacca to Kuantan Port. This will link the highly urbanised west coast of Peninsular Malaysia to its rural east coast.

From Kuantan, the rail link travels north through the state of Terengganu – which has never had a rail service before – into Malaysia’s poorest state of Kelantan where the railway terminates at an empty farmland just outside the state capital of Kota Bharu at the end of its 665km route.

Its core appeal is cost.

Malaysia wants Bangkok to tap into the ECRL landbridge to move its goods south, freeing up the tens of billions of dollars needed to build two deep seaports and supporting overland infrastructure in southern Thailand.

For the link to work, Malaysia needs to extend the line a further 33.5km from its current terminus to the existing Malayan Railway facility at the border, with a new railway yard to facilitate the transfer of goods linking the ECRL to and from the State Railway of Thailand’s wagons.

But the devil is in the details.

“This is not a small project and we estimate it will cost about 2 billion ringgit [US$430 million],” Loke said.

Malaysia has estimated a price tag of 50.27 billion ringgit (US$10.7 billion) for the ECRL’s construction.

Presenting it to the Malaysian Senate in Kuala Lumpur in March, Loke said modernised rail connectivity between Malaysia and Thailand was a “common good” that would boost economic growth on both sides.

US concerns about China’s involvement

Singapore and Malaysia have long enjoyed reaping the benefits of being located along the world’s second most important oil shipping route after the Straits of Hormuz.

The city state is developing its new Tuas Port, which will have an annual capacity of 65 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) of transshipment when completed in the 2040s.

Malaysia’s Westport expansion in Port Klang is projected to handle 27 million TEUs by 2053, doubling the volume of containers it handled in 2023.

The landbridge proposed by Thailand is expected to attract 25 million TEUs.

Unlike their Malaysian and Singapore rivals, Thailand’s existing ports of Laem Chabang and Bangkok, which have a combined handling capacity of 10.24 million TEUs, are not collectively considered a transshipment hub.

Speaking in parliament last November, Singapore Transport Minister Chee Hong Tat spoke about the proposed Thai landbridge and whether it would pose a major challenge to the city state’s ports.

“The exact time saving will depend on many factors, such as the time needed to unload the cargo from the vessel, transport it across the landbridge and load it onto the vessel at the other end. So they need to consider the overall costs versus benefits compared to sailing through the Strait of Malacca and Singapore,” Chee said.

Analysts say Singapore’s competitive advantages of the rule of law, technical expertise and political stability will put it in good stead to compete against Thailand’s landbridge.

“Singapore receives the highest geostrategic benefit of the Malacca Strait,” Chong added.

“[But] only because Singapore has an open economy that is relatively free from foreign influence. This serves as a critical reminder to Thailand … having an alternate route will not simply imply that it will dominate new routes which make existing port systems obsolete.”

When asked about the threat posed by the Thai landbridge last November, Malaysia’s Loke told reporters: “There is nothing to be worried about.”

A key node of the ECRL is the Malaysia- and China-owned Kuantan Port, which is being developed to increase its capacity from 150,000 TEUs annually in recent years.

But the ECRL has had false starts before.

Initially projected to cost 66.78 billion ringgit (US$14.21 billion), the ECRL was later revived at a lower cost.

Regardless of the outcome of Thailand’s landbridge plan, Malaysia should invest heavily in its rail link, said Aimi Zulhazmi, an economist at the Universiti Kuala Lumpur Business School.

He added: “It will connect Malaysia more strategically as a logistic and transport hub in the region to seaports on the south and west coasts.”