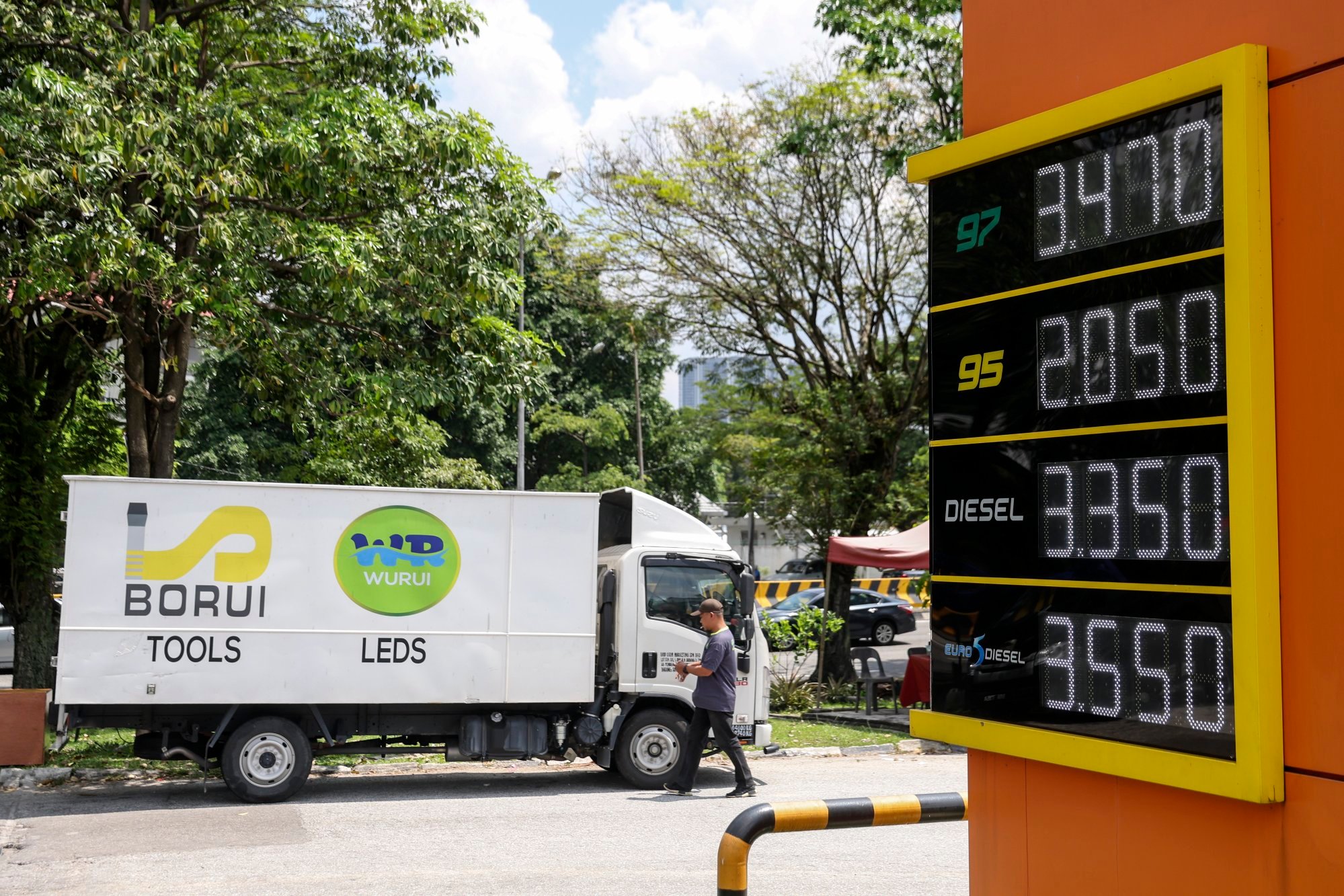

Domestic tour bus operators have already been forced to increase their rates by as much as 35 per cent, after prices at the pump surged overnight to 3.35 ringgit (71 US cents) from 2.15 ringgit before the subsidy cut.

“Even if the tour bus is not moving, we still need to leave the air conditioning on, otherwise our customers will complain,” Tai Pok Kim, secretary general of the Peninsular Malaysia Tour Bus Operators Association, told This Week in Asia.

If a company has 10 buses, you’re looking at 2,000 ringgit in losses a day

To cover an average of 400km (250 miles) per day, tour buses typically need about 150 litres (39.6 gallons) of fuel – meaning the daily cost of operation for each has increased by some 200 ringgit (US$42), he said.

“If a company has 10 buses, you’re looking at 2,000 ringgit in losses a day.”

Under the new subsidy system, selected logistics vehicles are allowed to buy diesel at the old 2.15-ringgit rate, while vehicles used for public transport and essential services – such as school and long-haul express buses, ambulances and fire engines – can still buy the fuel for 1.88 ringgit a litre.

But tour buses were excluded, with the government reasoning they mainly cater to foreign tourists. Heavy machinery typically used for construction does not qualify for the subsidised rate either, driving up downstream costs.

Small-scale farmers, smallholders and some drivers of diesel vehicles who fall into a specified low-income bracket are eligible to receive 200 ringgit in monthly cash aid by way of compensation.

The subsidy cut, which does not apply to the states of Sabah and Sarawak on Malaysian Borneo, is expected to save the government 4 billion ringgit (US$848 million) annually.

But some restaurant operators are worried that it will have the opposite effect on their bottom line.

“If our suppliers raise their prices, then I don’t think we have much of a choice but to raise ours,” said Ahmad, a manager of a 24-hour restaurant on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur who gave only one name as he was not authorised to speak to the media.

Theoretically, higher diesel prices should not translate into a huge surge in overall inflation as the fuel’s cost only makes up a very small portion – just 0.2 per cent – of the basket of goods and services used to calculate Malaysia’s official inflation rate.

But unscrupulous businesses may still use it as an excuse to price gouge, warns Mohd Afzanizam Abdul Rashid, chief economist at Bank Islam.

“The risk of profiteering is something that we cannot totally rule out despite some of the businesses maybe qualifying for subsidies,” Afzanizam told This Week in Asia.

“The businesses have no incentive to lower their prices … so strict enforcement of existing laws is crucial to curb profiteering.”

Yeah Kim Leng, an economics professor at Malaysia’s Sunway University, said the government has the financial resources available to offer support if inflation rises faster than anticipated.

“Further upward adjustment in the cash support would be possible in the unlikely situation of widespread hardship materialising due to an inflation spike,” Yeah said.

For some businesses, raising prices will be a last resort.

Jawahar Ali Taib Khan said his restaurant chain had managed to keep prices steady for several years now, absorbing the shock of fluctuating prices despite inflationary pressures.

“Now it’s a very tough time for everybody. That’s why we have not raised our prices so far,” he said.

“Our policy is very simple, we try to sell at very reasonable prices.”