JuJu Chan and Antony Szeto are a literal power couple. Chan, a 35-year-old action star who appeared in 2016’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon: Sword of Destiny, practises taekwondo, wing chun, Shaolin-style wushu, Muay Thai and karate. Her film-director husband, 59, is an expert in Chinese martial arts. Both also practise with weapons such as nunchucks.

“When you’re working with weapons like JuJu and I [do], you’re doing weighted training, while still doing forms and aerobic exercises,” Szeto says.

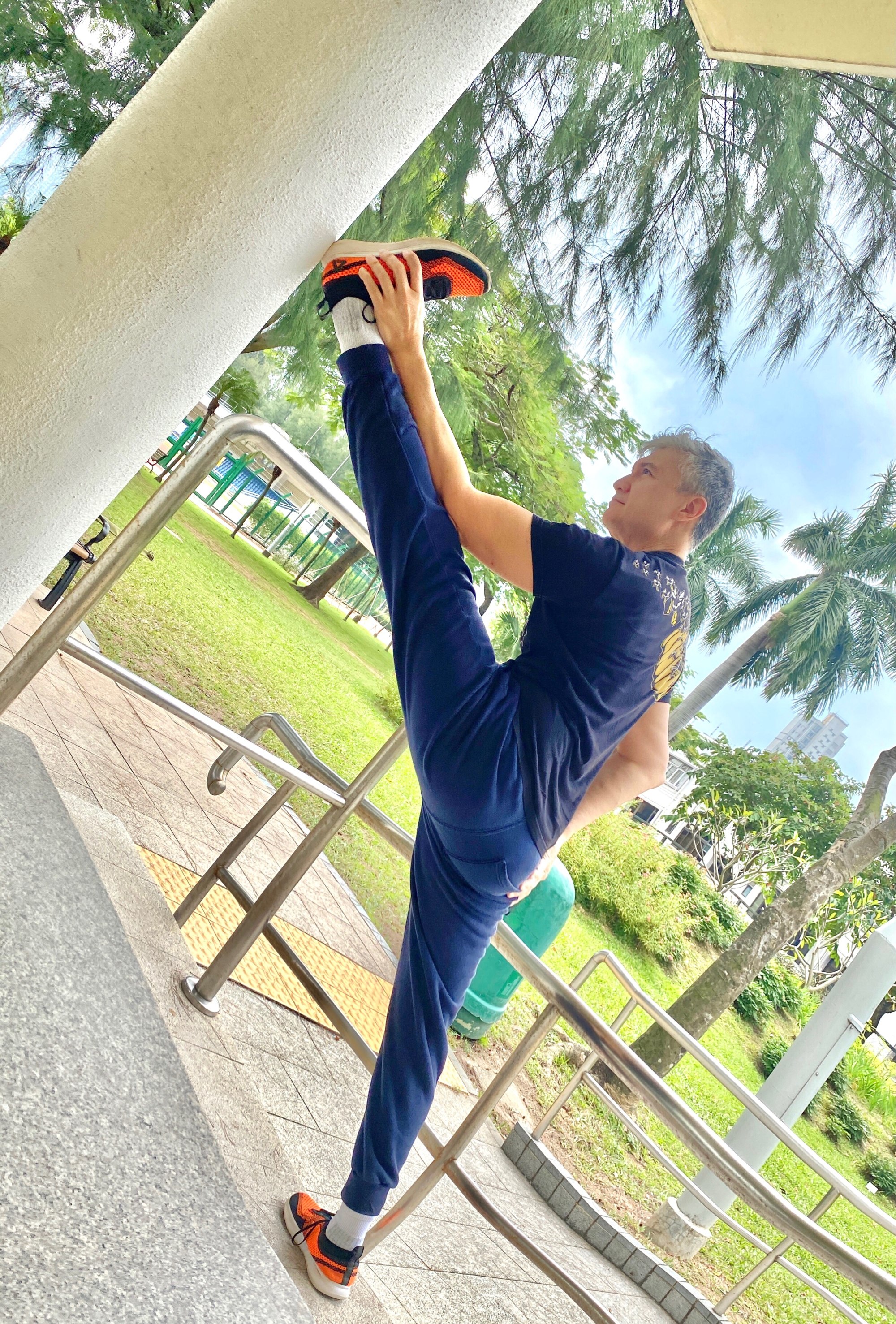

The results of all this practice are visible. “I can still do the splits,” he says.

“When I’m in the park and people see this white-haired guy going all the way down and doing a full split, they go ‘Wow!’ It’s really that suppleness. Working with aerobic exercises keeps you fit. Working with weighted weapons gives you skeletal muscles.”

But what may not be immediately obvious to martial arts spectators is that a lot is going on in a fighter’s head, says Chan, who represented Hong Kong in taekwondo from 2012-15 – winning a gold medal at the 2013 China Open Championship – and was the 46kg Thai boxing champion at the WMC The One Legend Thai Boxing Championship, held in Hong Kong.

“When you start competing, there are a lot of strategies, a lot of moves you need to mentally combine, all the while reading your opponents’ moves. It really works your brain,” she says.

Chan, who recently gave birth to their first child, found her martial arts training helped her healthily transition to a new phase of her life.

“When you’re pregnant and your hormones are doing their thing, you have moments when you are down and you feel that your body is not in shape. But a martial artist is a person who understands her own body. You know that you can get back to how you were before,” Chan says.

Chan started learning judo at 10, while Szeto learned taekwondo and Choy Li Fut – one of the major southern Chinese styles of wushu – when he was growing up in Australia. He eventually moved to China to advance his training.

“I trained with the wushu faculty of the Beijing Sports University from 1986 to 1988, where I learned all the different styles of Chinese martial arts including Sanda, which is the actual fighting,” says Szeto, referring to the Chinese combat sport. He ended up representing Australia at the International Invitational Wushu Championships in Hangzhou in 1988.

To anyone who wants to start martial arts, Szeto suggests that they try out different styles to see what fits.

“The best martial art is the one you’re willing to stick with. For example, a lot of people say Brazilian jiu-jitsu is the best thing because it’s practical. Well, I tried it and I hated it. I did not like having somebody’s butt sitting on my face, and working under somebody’s arm,” he says.

“I like stand-up martial arts. I like the stuff where I’m kicking. So the best martial arts style for anyone is the one that makes you keep going back.”

Chan says there are benefits to learning different kinds of martial arts: the fundamental techniques are very similar, and just like learning different languages, the more styles you know, the easier it gets for you to learn even more.

There is no question that Chan and Szeto’s newborn daughter will learn martial arts – it would be as natural as other parents teaching their children how to swim – but they will not pressure her to pursue it professionally.

There are reasons to believe that the two-month-old has already begun picking it up.

“The other day, I was doing nunchucks at home and she was tracing my movements with her eyes without even blinking, mesmerised,” Chan says. “Even in the womb, she was kicking a lot.”