While Kharel received timely treatment, many others in Nepal are less fortunate. Snakebites remain a pervasive and deadly threat in the country, especially among its rural populations, but experts believe that targeted awareness campaigns and increased treatment access could halve the number of fatalities.

A 2022 research in the medical journal The Lancet, which is said to be the first snakebite epidemiological study in Nepal, estimated that there were as many as 37,661 snakebite cases and 3,225 deaths annually in the country’s southern plains. However, the government’s hospital-reported data from the past two decades show an average of 20,000 hospitalisations and about 1,000 deaths every year.

In 2017, the WHO listed snakebites as a neglected tropical disease due to a lack of attention it receives from the global health agenda.

In countries like Nepal, doctors say a reliance on traditional healers and unproven techniques, as well as delays in receiving critical medical interventions during the first few hours after being bitten, often lead to deaths.

“Around 80 per cent of people die before reaching hospitals,” Sanjib Kumar Sharma, a professor at the BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences in eastern Nepal, told This Week in Asia. “The cause of death is often due to delay in transport.”

‘Neglected disease’

The districts in Nepal’s southern lowlands are the most vulnerable to snakebites due to the warmer climate and reptile habitats throughout the region. There are some 89 species of snakes in Nepal, though most common bites come from the cobra, krait and viper families.

Research and anecdotal evidence from doctors show that snakebites disproportionately affect women and children in Nepal’s remote villages, both indoors and outdoors.

Many girls and women have succumbed to snakebites while staying in outdoor spaces during menstruation due to archaic Hindu traditions that banishes them during their monthly cycle.

Krishna Acharya, an anaesthesiologist who worked in the government-run Bheri Hospital in Nepalgunj, treated over 2,000 snakebite patients during his eight-year tenure that ended this year.

He was initially untrained to handle snakebite patients but received training after seeing an influx of patients who had their care delayed after having to be referred to a designated snakebite treatment centre.

It’s a neglected disease because it affects the poor, and those in the city, expect a few exceptions, aren’t affected by snakebites. That’s why there’s little interest in it

There are more than 110 snakebite treatment centres nationwide, mostly in public hospitals or treatment centres that are run by the Nepali army and Nepal Red Cross. The government has also published national guidelines for snakebite management – detailing clinical manifestations, diagnosis and management of snakebite envenoming – and provides free antivenom vials.

But doctors say that is not enough, as the country lacks trained medical professionals to manage snakebites and treatments can be expensive.

Snakebite treatment costs about 10,000 rupees (US$75) on average and can go as high as 400,000 rupees if patients require intensive care and life support, an astronomical amount for many living in Nepal’s villages, according to Acharya.

Acharya, who now works at Kathmandu’s National Trauma Centre, said the country’s medical colleges rarely teach about snakebites, resulting in doctors being unable to handle such cases. Sharma recommended that chapters on locally found snakes and treatment techniques be included in the curriculum.

“Many people who shouldn’t die of snakebites are dying in Nepal,” Acharya said. “It’s a neglected disease because it affects the poor. Those in the city, except for a few exceptions, aren’t affected by snakebites. That’s why there’s little interest in it.”

Not all snakes are venomous

Kamal Devkota, a conservation biologist, has been studying snakes for years and works at the Nepal Toxinology Association to research and educate people on snakebites and snake conservation.

Though snakes are worshipped in Hinduism, a predominant religion in Nepal, he said people largely kill snakes out of fear and a lack of information about poisonous species.

Devkota said that habitat loss due to infrastructure development and wildfire in summer months have pushed many snake species into human settlements, mostly in search of food. Human-snake conflict has led to not just an increased number of snakebites but also the killing of snakes, which has an impact on the ecosystem.

“Snakes are said to be farmers’ friends,” Devkota told This Week in Asia. “They help in pest control in farms, which would help increase productivity and also minimise the use of pesticides. If their population decreases, then it also impacts other birds of prey that depend on snakes.”

Doctors and conservationists say the reptiles are also important medically, especially in Nepal, for research into life-saving antivenoms for lesser known and newly found poisonous snakes. Currently, Nepal imports antivenoms from India which are mostly made for “the big four” available there – the Indian cobra, common krait, Russell’s viper and the saw-scaled viper.

Limited antivenom imports mean there is often short supply in treatment centres and doctors say their effectiveness for certain species is lower and carries higher chances of causing adverse reactions in patients.

“We need regional antivenom specific to local snakes,” said Sharma, also the co-author of The Lancet study.

But so far, Nepal does not have plans to invest in producing its own antivenoms and efforts by private companies have not materialised yet.

“How much of the antivenom produced in Nepal will be put into use?” asked Hemant Chandra Ojha, chief of the zoonotic and communicable disease control section in Nepal’s Epidemiology and Disease Control Division. “The demand is very low, so it wouldn’t be sustainable.”

Push for awareness

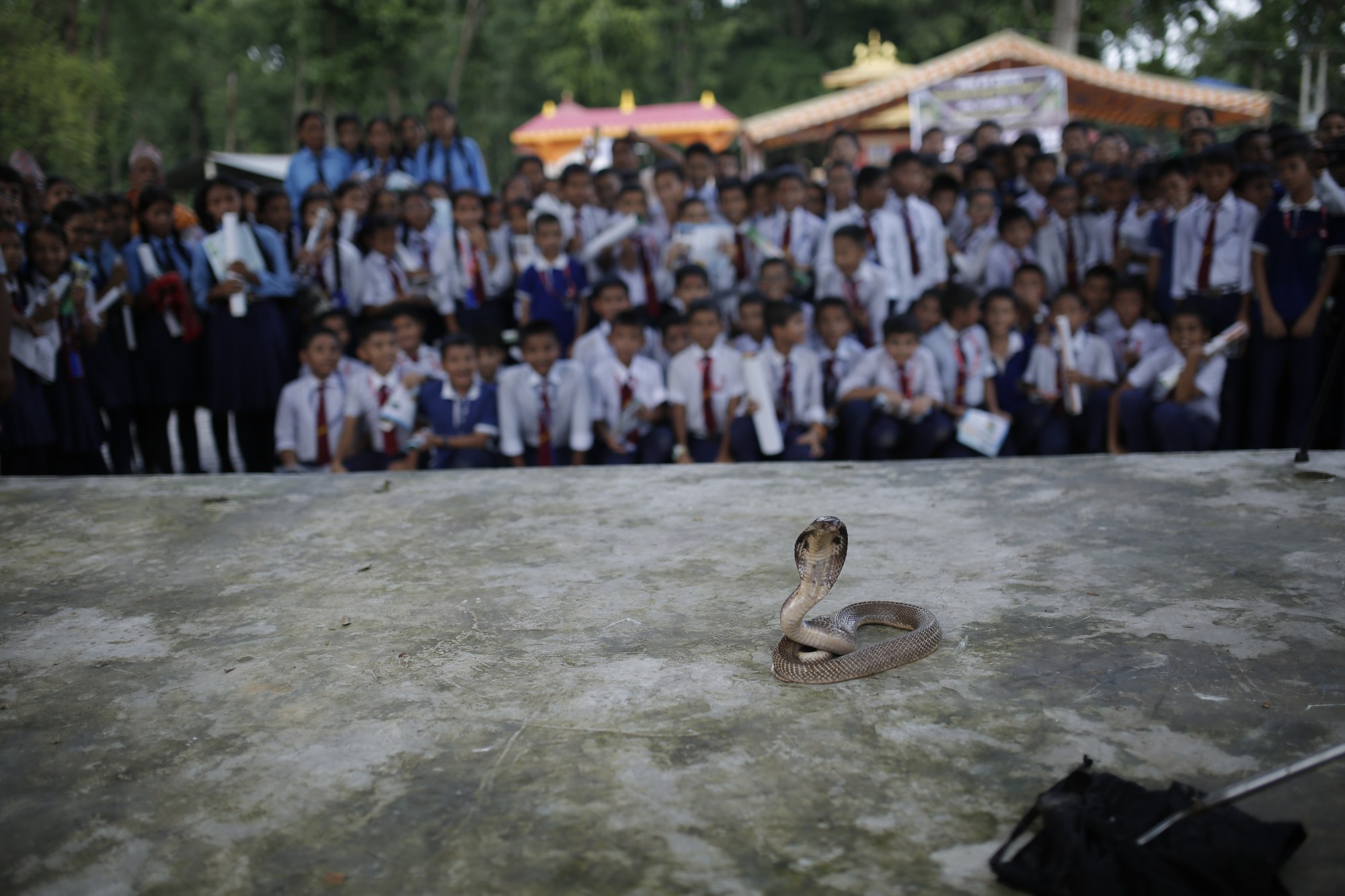

Experts say one of the major ways to save lives from snakebites is through public awareness campaigns at the community level. Another is expanding snakebite treatment centres offering antivenoms in remote areas.

The Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, along with the Rotary Club of Kathmandu Mid-Town, have initiated campaigns to disseminate information on preventive measures using local languages spoken in the southern region. They include messages to households about keeping their surroundings clean, sleeping under a net, and being aware of walking at night, when there is greater chances of snakebites.

However, Acharya believes that awareness campaigns highlighting preventive measures are not enough to save lives.

“People need to have information on where the snakebite treatment centres are and they should be easily accessible to them for timely care,” he said. “If we have targeted campaigns and focus on snakebite affected areas, the mortality can be halved.”

Meanwhile, there are also initiatives to train more healthcare providers, including paramedics, who doctors say play a crucial role in saving people from snakebites.

Ojha said that the government is educating medical students at its National Academy of Medical Sciences, who are deployed to various government hospitals after graduating, as well as scaling up services in at-risk areas and adding new human resources annually through training.

At the community level, snakebite survivors like Khanal are also helping raise awareness. She said those in her neighbourhood have become more conscientious after last year’s incident.

“I mostly share what I experienced,” she said. “I tell them that you need to go to the hospital as soon as possible. They saw how it helped me survive, so people around me are more aware now.”